Browse By Unit

Dalia Savy

Robby May

Dalia Savy

Robby May

Origins of the Cold War

The Cold War dominated international relations from the late 1940s to the collapse of the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1991. The conflict centered around the intense rivalry between two superpowers: the Communist empire of the Soviet Union and the leading Western democracy, the United States. Superpower competition was usually through diplomacy and not through conflict, but in several instances, the Cold War took the world dangerously close to nuclear war.

The founding of the United Nations (UN) in 1945 provided a hopeful sign for the future. The General Assembly of the United Nations was created to provide representation to all member nations, while the 15-member Security Council was given the primary responsibility within the UN for maintaining international security and authorizing peacekeeping missions. The five major allies of wartime, the U.S., Great Britain, France, China, and the Soviet Union were granted permanent seats and veto power in the UN Security Council. Optimists hoped that these nations would be able to reach an agreement on international issues.

FDR and Churchill decided that instead of informing their major ally of the developing atomic bomb, they kept it a closely guarded secret. Stalin learned of the Manhattan Project through espionage and responded by starting the Soviet atomic program in 1943. By the time Truman told Stalin, the USSR was way on their way to make their own bomb.

Satellite States

Distrust turned into hostility in 1946, as Soviet forces remained in occupation of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Elections were held by the Soviets—as promised by Stalin at Yalta—but the results were manipulated in favor of Communist candidates. Communist dictators, most of them loyal to Moscow, came to power in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia.

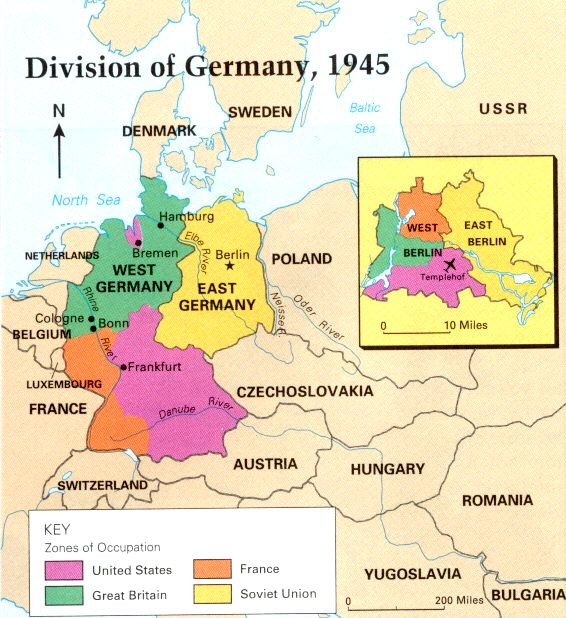

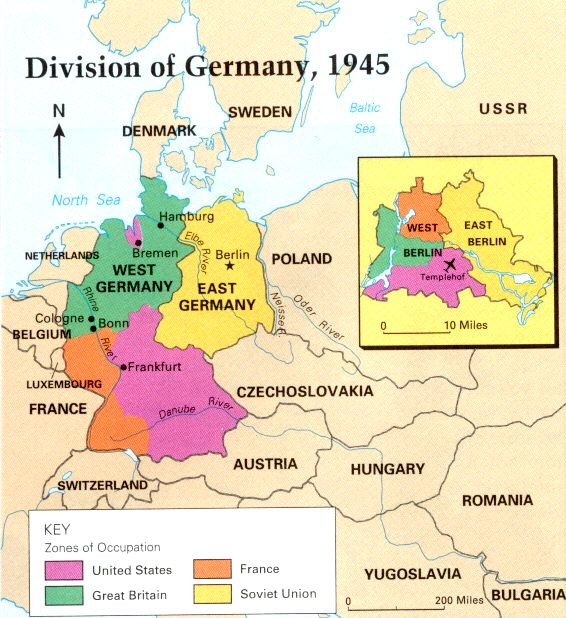

Division of Germany

At the end of the war, the division of Germany into Soviet, French, British, and U.S. zones of occupation was meant to be only temporary. In Germany however, the Eastern zone under Soviet occupation gradually evolved into a new Communist state: the German Democratic Republic.

The US and Great Britain merged their zones and championed the idea of unification of all of Germany. They refused to allow reparations from their zones as they viewed the economic recovery of Germany as important to the stability of Central Europe. Russia feared a resurgence of German military power and responded by intensifying the communization of its zone, including the jointly occupied city of Berlin.

Image Courtesy of Reformation

Iron Curtain

In March 1946, in Fulton, Missouri, Truman was present on the speaker’s platform as former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill declared “An iron curtain has descended across the continent” of Europe. The iron curtain metaphor was later used throughout the Cold War to refer to the Soviet satellite states of Eastern Europe.

Truman’s Containment Policy

Early in 1947, President Truman adopted the advice of three top advisers in deciding to “contain” Soviet aggression. The containment policy would dominate U.S. foreign policy for decades.

Truman Doctrine

Truman first implemented the containment policy in response to two threats:

- A Communist-led uprising against the government in Greece

- Soviet demands for some control of a water route in Turkey, the Dardanelles. In what became known as the Truman Doctrine, the president asked Congress for $400 million in economic and military aid to assist the “free people” of Greece and Turkey against “totalitarian” regimes. The Truman Doctrine was an informal declaration of the Cold War against the Soviet Union.

Marshall Plan

Despite $9 billion in American loans, England, France, Italy, and other European nations had great difficulty in recovering from World War II. Food was scarce, with millions existing on less than 1500 calories a day. Industrial machinery was broken down and obsolete workers were demoralized from years of depression and war. Resentment and discontent led to growing communist voting strength. If the US could not reverse the process, all of Europe would drift into communist orbit.

George Marshall drew up a plan for a massive infusion of American capital to finance the economic recovery of Europe. Truman presented this 12 billion was approved in aid for distribution to the countries of Western Europe to recover from the Second World War.

The plan worked exactly as Marshall and Truman had hoped. The massive infusion of U.S. dollars helped Western Europe achieve self-sustaining growth by the 1950s and ended any real threat of Communist political successes in that region. It also greatly increased US exports to Europe.

Berlin Airlift

Stalin decided to cut off all rail and highway traffic to Berlin (called the Berlin Blockade). Truman decided that they were staying put. He rejected proposals that would have created a showdown and instead adopted a two-phase policy:

- First, there would be a massive airlift of food, fuel, and supplies for the ten thousand troops and two million civilians in Berlin. A fleet of planes began making two daily roundtrip flights to Berlin. This became known as the Berlin Airlift.

- Second, Truman transferred 60 American B-29s, planes capable of delivering atomic bombs, to bases in England. The president was bluffing as the planes were not actually equipped with bombs. Stalin did not attempt to disrupt the flights. At any time, the Soviets could have halted it by jamming radar or shooting down defenseless cargo planes. The Soviets gave in, in 1949, ending the blockade.

Image Courtesy of Wikipedia

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

The U.S., 10 European nations, and Canada signed the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington on April 4, 1949. There were two main features of NATO:

- The US committed itself to the defense of Europe in the key clause which stated: “an armed attack against one or more shall be considered an attack against them all”. The US was extending the atomic shield over Europe.

- Truman appointed General Dwight Eisenhower to the post of NATO supreme commander and authorized the stationing of four American divisions in Europe to serve as the nucleus of the NATO army. They felt this threat would deter Russian assault.

The Chinese Civil War

When the war ended, China was torn between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists in the South and Mao Tse-tung’s Communists in the North. Chiang had many advantages including American political and economic backing and official Soviet recognition. However, corruption was widespread amongst the Nationalist leaders and inflation soon reached 100% and devastated the middle class. Mao used tight discipline and patriotic appeals to strengthen his hold on the peasantry and extend his influence. A civil war between the two groups started.

Image Courtesy of Britannica

By 1947, Chiang’s army was in retreat. Truman ruled out a large-scale invasion to save Chiang. Congress voted to give $400 million in aid to the Nationalist government, but 84% of the U.S. military supplies ended up in Communist hands because of corruption.

By the end of 1949, all of mainland China was controlled by the Communists. The Communists drove the Nationalists out and then fled mainland China to the island of Formosa (Taiwan). From there, Chiang still claimed to be the legitimate government of China. Mao and Stalin signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance that clearly placed China in the Soviet orbit.

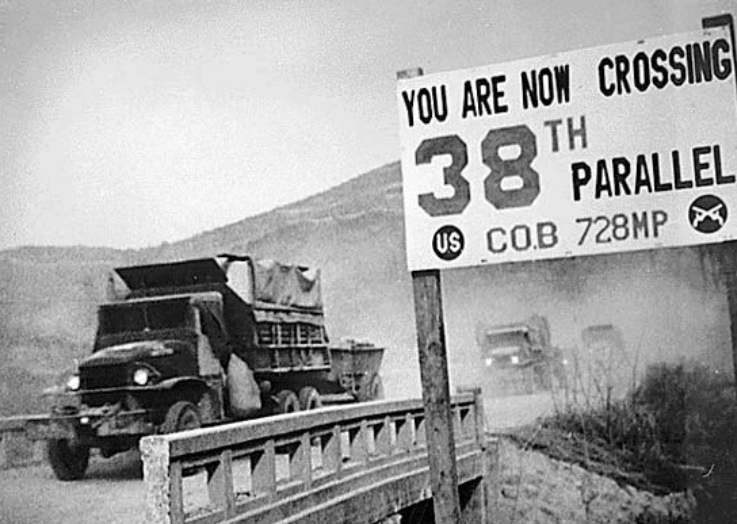

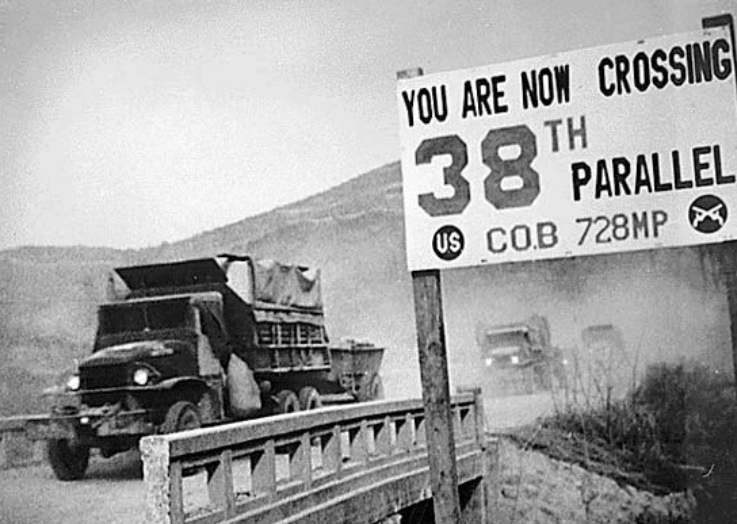

The Korean War

After the defeat of Japan, its former colony of Korea was divided along the 38th parallel by the victors. Soviet armies occupied Korean territory north of the line, while U.S. forces occupied territory to the south. By 1949, both armies were withdrawn, leaving the North in the hands of Communist leader Kim Il Sung and the South under the conservative nationalist Syngman Rhee.

On July 25, 1950, the North Korean army suddenly crossed the 38th parallel with great strength, surprising the world. Stalin had approved the act of aggression in advance. Stalin warned Kim not to count on Soviet assistance, telling him, “If you should get kicked in the teeth, I shall not lift a finger.”

Image Courtesy of Britannica

Truman took immediate action, applying his containment policy to this latest crisis in Asia. He called for a special session of the UN Security Council. Taking advantage of a temporary boycott by the Soviet delegation, the Security Council under U.S. leadership authorized a UN force to defend South Korea against the invaders. Commanding the expedition was General Douglas MacArthur. Congress supported the use of US troops, but failed to declare war, accepting Truman’s characterization of US intervention as merely a “police action."

Beijing continued to warn the U.S. not to invade North Korea. The CIA warned that the Chinese were assembling a massive force on the border. Truman and his advisors believed that the Soviet Union, not ready for all-out war, would hold China in check. MacArthur agreed. When the UN forces crossed the 38th parallel, the Chinese launched a devastating counterattack and caught MacArthur by surprise and his armies were driven out of North Korea.

Truman decided to give up on his attempt to unify Korea and MacArthur protested to Congress. As a result, Truman relieved the popular hero of the Pacific of his command on April 11, 1951. When MacArthur came home, he was met by huge crowds to welcome him and hear him call for victory over the Communists.

Soon after his inauguration in 1953, Eisenhower kept his promise by going to Korea to visit UN forces and see what could be done to stop the war. Diplomacy, the threat of nuclear war, and the sudden death of Josef Stalin in March of 1953 finally moved China and North Korea to agree to an armistice and an exchange of prisoners in July of 1953.

An armistice was finally signed in 1953 during the first year of Eisenhower’s presidency. Korea would remain divided at the 38th parallel, and despite years of futile negotiations, no peace treaty was ever concluded between North and South Korea.

Massive Retaliation

In 1953 under Eisenhower, the US developed the hydrogen bomb, which was 1000x more powerful than the atomic bomb. Within a year, the Soviets caught up with a bomb of their own.

To some, the policy of massive retaliation looked more like a policy for mutual extinction. The idea of mutually assured destruction came about and held off both sides from launching a nuclear weapon at one another during the Cold War. The idea is that once one nation fires a nuclear weapon, the other nation will do the same, continuing a back-and-forth exchange, until both nations, and most likely others, are completely destroyed.

Nuclear weapons indeed proved a powerful deterrent against the superpowers fighting an all-out war between themselves, but such weapons could not prevent small “brushfire” wars from breaking in the developing nations of Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

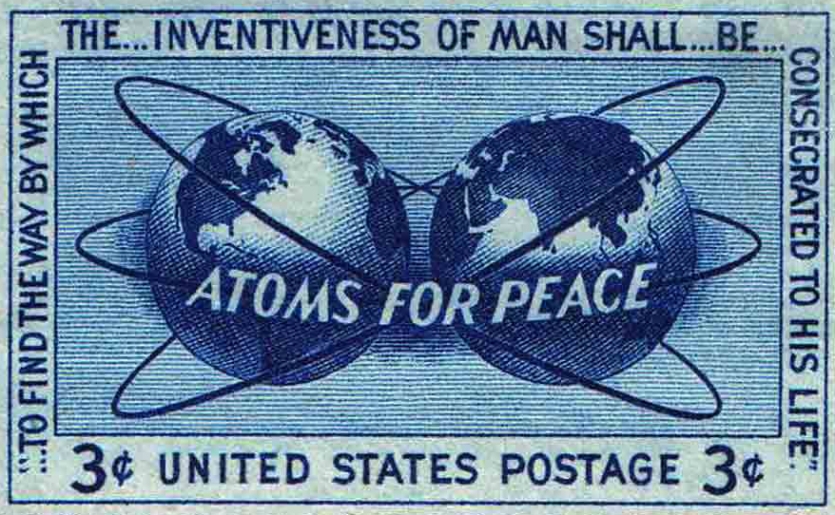

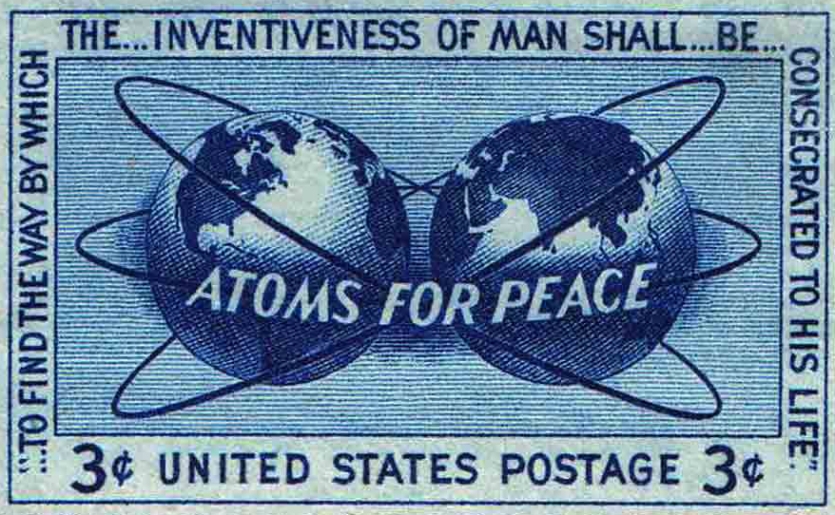

Geneva Convention

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Eisenhower called for a slowdown in the arms race and presented to the U.S. the atoms for peace plan. In 1955, there was a summit meeting between both sides in Geneva, Switzerland.

Image Courtesy of Science History Institute

At this conference, the U.S. proposed an “open skies” policy over each other’s territory, open to aerial photography by the opposing nation, in order to eliminate the chance of a surprise nuclear attack. The Soviets rejected the proposal. Nevertheless, a “spirit of Geneva” as the press called it, produce the first thaw in the Cold War.

U-2 Incident

The Russians shot down a high-altitude US spy plane, the U-2, over the Soviet Union. The incident exposed a secret U.S. tactic for gaining information. After the open skies proposals had been rejected by the Soviets, the U.S. decided to conduct regular spy flights over Soviet territory to find out about its enemy’s missile program.

Eisenhower took full responsibility for the flights AFTER they were exposed by the U-2 incident, but his honesty proved to be a diplomatic mistake. Khrushchev, the secretary of the USSR, denounced the U.S. and walked out of the Paris summit to temporarily end the thaw in the Cold War.

Communism in Cuba

Fidel Castro overthrew the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959. Once in power, Castro nationalized American-owned businesses and properties in Cuba. Eisenhower retaliated by cutting off U.S. trade with Cuba.

Castro then turned to the Soviets for support. He revealed that he was a Marxist and soon proved it by setting up a Communist totalitarian state. With communism only 90 miles off the shores of Florida, Eisenhower authorized the CIA to train anti-communist Cuban exiles to retake their land, but the decision to go ahead was left up to the next president, Kennedy.

Bay of Pigs Invasion

Kennedy made a major blunder shortly after entering office. He approved a Central Intelligence Agency scheme planned under Eisenhower to use Cuban exiles to overthrow Fidel Castro’s regime in Cuba. In April of 1961, 1400 Cuban exiles moved ashore at the Bay of Pigs on the southern coast of Cuba. They failed to set off a general uprising as planned. Castro’s forces had air superiority and had no difficulty quashing the invasion. They killed nearly 500 exiles and the rest surrendered. Kennedy was shocked by the swiftness of the defeat and took personal responsibility for the Bay of Pigs.

Kennedy and Berlin

A steady flight of skilled workers to the West through the Berlin escape route weakened the East German regime dangerously. The Soviets sealed off their zone of the city. They began the construction of the Berlin Wall to stop the flow of brains and talent to the West. Russian and American tanks maneuvered within sight of each other at Checkpoint Charlie (where the two zones met).

On July 25, Kennedy delivered an impassioned televised address to the American people in which he called the defense of Berlin essential to the entire Free World. To cheering crowds, he proclaimed “Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put up a wall to keep our people in…as a free man, I take pride in the words. Ich bin ein Berliner (I am a Berliner)."

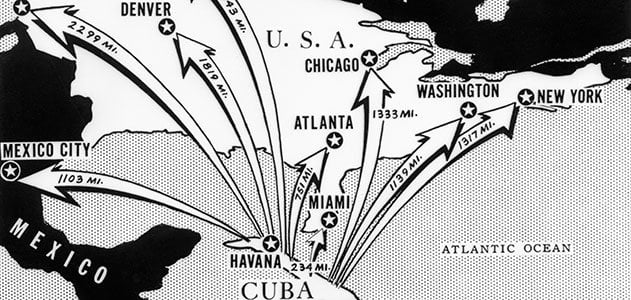

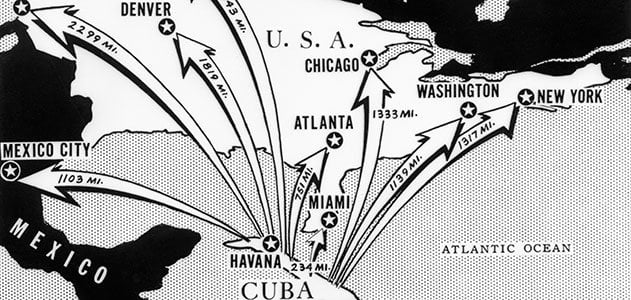

Cuban Missile Crisis

Throughout the summer and early fall of 1962, the Soviets engaged in a massive arms buildup in Cuba, to protect Cuba from American invasion. Kennedy issued a stern warning against any offensive weapons in Cuba. Secretly, Khrushchev was building sites for 24 medium-range (1000 mile) and 18 intermediate-range (2000 mile) missiles in Cuba. He later claimed his purpose was purely defensive, but most likely he was responding to the pressures from his own military to close the enormous strategic gap in nuclear striking power.

Image Courtesy of Smithsonian Magazine

Kennedy allowed U-2 flights over Cuba. The first mission brought back indisputable photographic evidence of the missile sites, which were nearing completion. Kennedy decided to keep the information secret while he consulted with a hand-picked group of advisers to consider how to respond, a group that would become known as ExComm.

Kennedy agreed to a two-step procedure:

- He would proclaim a quarantine of Cuba to prevent the arrival of new missiles.

- He would threaten a nuclear confrontation to force the removal of those already there. On the evening of October 22, the president informed the nation of the existence of the Soviet missiles and his plans to remove them. For the next 6 days, the world hovered on the brink of nuclear war.

In the Atlantic, 16 Soviet ships continued on course towards Cuba, while the American navy was deployed to intercept them 500 miles from the island.

Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles in return for Kennedy’s promise not to invade Cuba and to later remove some U.S. missiles from Turkey. The crisis was over. Shaken by their close call, Kennedy and Khrushchev agreed to install a “hotline” to speed direct communication between Washington and Moscow in an emergency.

Détente

Nixon and Kissinger strengthened the US position in the world by taking advantage of the rivalry between the two Communist giants, China and the Soviet Union. Their diplomacy was praised for bringing about détente—a deliberate reduction of Cold War tensions.

Nixon planned to use American trade, notably grain and high technology, to induce Soviet cooperation, while at the same time improving U.S.-China relations. In 1972, Nixon visited China, meeting with the Communist leaders and ending more than two decades of Sino-American hostility.

He agreed to establish an American liaison mission in Beijing as the first step toward diplomatic recognition. The Soviets, who viewed China as a dangerous adversary, responded by agreeing to an arms control pact with the United States.

Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) had been underway since 1969. During a visit to Moscow in 1972, Nixon signed two vital documents with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. This would be known as SALT I:

- The first limited the two superpowers to two hundred antiballistic missiles apiece.

- The second froze the number of ballistic missiles for a 5-year period. This was the most important first step toward control of the nuclear arms race.

Carter and the Cold War

Carter signed the SALT II treaty with the Soviet Union in 1979, which provided for limiting the size of each superpower’s nuclear delivery system. The Senate never ratified the treaty.

The Cold War resumed with full fury when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979. The U.S. feared that the invasion might lead to a Soviet move to control the oil-rich Persian Gulf.

Carter reacted by issuing what became known as the Carter Doctrine which:

- halting grain exports and high technology to the Soviet Union

- and boycotting the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow.

<< Hide Menu

Dalia Savy

Robby May

Dalia Savy

Robby May

Origins of the Cold War

The Cold War dominated international relations from the late 1940s to the collapse of the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1991. The conflict centered around the intense rivalry between two superpowers: the Communist empire of the Soviet Union and the leading Western democracy, the United States. Superpower competition was usually through diplomacy and not through conflict, but in several instances, the Cold War took the world dangerously close to nuclear war.

The founding of the United Nations (UN) in 1945 provided a hopeful sign for the future. The General Assembly of the United Nations was created to provide representation to all member nations, while the 15-member Security Council was given the primary responsibility within the UN for maintaining international security and authorizing peacekeeping missions. The five major allies of wartime, the U.S., Great Britain, France, China, and the Soviet Union were granted permanent seats and veto power in the UN Security Council. Optimists hoped that these nations would be able to reach an agreement on international issues.

FDR and Churchill decided that instead of informing their major ally of the developing atomic bomb, they kept it a closely guarded secret. Stalin learned of the Manhattan Project through espionage and responded by starting the Soviet atomic program in 1943. By the time Truman told Stalin, the USSR was way on their way to make their own bomb.

Satellite States

Distrust turned into hostility in 1946, as Soviet forces remained in occupation of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Elections were held by the Soviets—as promised by Stalin at Yalta—but the results were manipulated in favor of Communist candidates. Communist dictators, most of them loyal to Moscow, came to power in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia.

Division of Germany

At the end of the war, the division of Germany into Soviet, French, British, and U.S. zones of occupation was meant to be only temporary. In Germany however, the Eastern zone under Soviet occupation gradually evolved into a new Communist state: the German Democratic Republic.

The US and Great Britain merged their zones and championed the idea of unification of all of Germany. They refused to allow reparations from their zones as they viewed the economic recovery of Germany as important to the stability of Central Europe. Russia feared a resurgence of German military power and responded by intensifying the communization of its zone, including the jointly occupied city of Berlin.

Image Courtesy of Reformation

Iron Curtain

In March 1946, in Fulton, Missouri, Truman was present on the speaker’s platform as former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill declared “An iron curtain has descended across the continent” of Europe. The iron curtain metaphor was later used throughout the Cold War to refer to the Soviet satellite states of Eastern Europe.

Truman’s Containment Policy

Early in 1947, President Truman adopted the advice of three top advisers in deciding to “contain” Soviet aggression. The containment policy would dominate U.S. foreign policy for decades.

Truman Doctrine

Truman first implemented the containment policy in response to two threats:

- A Communist-led uprising against the government in Greece

- Soviet demands for some control of a water route in Turkey, the Dardanelles. In what became known as the Truman Doctrine, the president asked Congress for $400 million in economic and military aid to assist the “free people” of Greece and Turkey against “totalitarian” regimes. The Truman Doctrine was an informal declaration of the Cold War against the Soviet Union.

Marshall Plan

Despite $9 billion in American loans, England, France, Italy, and other European nations had great difficulty in recovering from World War II. Food was scarce, with millions existing on less than 1500 calories a day. Industrial machinery was broken down and obsolete workers were demoralized from years of depression and war. Resentment and discontent led to growing communist voting strength. If the US could not reverse the process, all of Europe would drift into communist orbit.

George Marshall drew up a plan for a massive infusion of American capital to finance the economic recovery of Europe. Truman presented this 12 billion was approved in aid for distribution to the countries of Western Europe to recover from the Second World War.

The plan worked exactly as Marshall and Truman had hoped. The massive infusion of U.S. dollars helped Western Europe achieve self-sustaining growth by the 1950s and ended any real threat of Communist political successes in that region. It also greatly increased US exports to Europe.

Berlin Airlift

Stalin decided to cut off all rail and highway traffic to Berlin (called the Berlin Blockade). Truman decided that they were staying put. He rejected proposals that would have created a showdown and instead adopted a two-phase policy:

- First, there would be a massive airlift of food, fuel, and supplies for the ten thousand troops and two million civilians in Berlin. A fleet of planes began making two daily roundtrip flights to Berlin. This became known as the Berlin Airlift.

- Second, Truman transferred 60 American B-29s, planes capable of delivering atomic bombs, to bases in England. The president was bluffing as the planes were not actually equipped with bombs. Stalin did not attempt to disrupt the flights. At any time, the Soviets could have halted it by jamming radar or shooting down defenseless cargo planes. The Soviets gave in, in 1949, ending the blockade.

Image Courtesy of Wikipedia

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

The U.S., 10 European nations, and Canada signed the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington on April 4, 1949. There were two main features of NATO:

- The US committed itself to the defense of Europe in the key clause which stated: “an armed attack against one or more shall be considered an attack against them all”. The US was extending the atomic shield over Europe.

- Truman appointed General Dwight Eisenhower to the post of NATO supreme commander and authorized the stationing of four American divisions in Europe to serve as the nucleus of the NATO army. They felt this threat would deter Russian assault.

The Chinese Civil War

When the war ended, China was torn between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists in the South and Mao Tse-tung’s Communists in the North. Chiang had many advantages including American political and economic backing and official Soviet recognition. However, corruption was widespread amongst the Nationalist leaders and inflation soon reached 100% and devastated the middle class. Mao used tight discipline and patriotic appeals to strengthen his hold on the peasantry and extend his influence. A civil war between the two groups started.

Image Courtesy of Britannica

By 1947, Chiang’s army was in retreat. Truman ruled out a large-scale invasion to save Chiang. Congress voted to give $400 million in aid to the Nationalist government, but 84% of the U.S. military supplies ended up in Communist hands because of corruption.

By the end of 1949, all of mainland China was controlled by the Communists. The Communists drove the Nationalists out and then fled mainland China to the island of Formosa (Taiwan). From there, Chiang still claimed to be the legitimate government of China. Mao and Stalin signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance that clearly placed China in the Soviet orbit.

The Korean War

After the defeat of Japan, its former colony of Korea was divided along the 38th parallel by the victors. Soviet armies occupied Korean territory north of the line, while U.S. forces occupied territory to the south. By 1949, both armies were withdrawn, leaving the North in the hands of Communist leader Kim Il Sung and the South under the conservative nationalist Syngman Rhee.

On July 25, 1950, the North Korean army suddenly crossed the 38th parallel with great strength, surprising the world. Stalin had approved the act of aggression in advance. Stalin warned Kim not to count on Soviet assistance, telling him, “If you should get kicked in the teeth, I shall not lift a finger.”

Image Courtesy of Britannica

Truman took immediate action, applying his containment policy to this latest crisis in Asia. He called for a special session of the UN Security Council. Taking advantage of a temporary boycott by the Soviet delegation, the Security Council under U.S. leadership authorized a UN force to defend South Korea against the invaders. Commanding the expedition was General Douglas MacArthur. Congress supported the use of US troops, but failed to declare war, accepting Truman’s characterization of US intervention as merely a “police action."

Beijing continued to warn the U.S. not to invade North Korea. The CIA warned that the Chinese were assembling a massive force on the border. Truman and his advisors believed that the Soviet Union, not ready for all-out war, would hold China in check. MacArthur agreed. When the UN forces crossed the 38th parallel, the Chinese launched a devastating counterattack and caught MacArthur by surprise and his armies were driven out of North Korea.

Truman decided to give up on his attempt to unify Korea and MacArthur protested to Congress. As a result, Truman relieved the popular hero of the Pacific of his command on April 11, 1951. When MacArthur came home, he was met by huge crowds to welcome him and hear him call for victory over the Communists.

Soon after his inauguration in 1953, Eisenhower kept his promise by going to Korea to visit UN forces and see what could be done to stop the war. Diplomacy, the threat of nuclear war, and the sudden death of Josef Stalin in March of 1953 finally moved China and North Korea to agree to an armistice and an exchange of prisoners in July of 1953.

An armistice was finally signed in 1953 during the first year of Eisenhower’s presidency. Korea would remain divided at the 38th parallel, and despite years of futile negotiations, no peace treaty was ever concluded between North and South Korea.

Massive Retaliation

In 1953 under Eisenhower, the US developed the hydrogen bomb, which was 1000x more powerful than the atomic bomb. Within a year, the Soviets caught up with a bomb of their own.

To some, the policy of massive retaliation looked more like a policy for mutual extinction. The idea of mutually assured destruction came about and held off both sides from launching a nuclear weapon at one another during the Cold War. The idea is that once one nation fires a nuclear weapon, the other nation will do the same, continuing a back-and-forth exchange, until both nations, and most likely others, are completely destroyed.

Nuclear weapons indeed proved a powerful deterrent against the superpowers fighting an all-out war between themselves, but such weapons could not prevent small “brushfire” wars from breaking in the developing nations of Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

Geneva Convention

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Eisenhower called for a slowdown in the arms race and presented to the U.S. the atoms for peace plan. In 1955, there was a summit meeting between both sides in Geneva, Switzerland.

Image Courtesy of Science History Institute

At this conference, the U.S. proposed an “open skies” policy over each other’s territory, open to aerial photography by the opposing nation, in order to eliminate the chance of a surprise nuclear attack. The Soviets rejected the proposal. Nevertheless, a “spirit of Geneva” as the press called it, produce the first thaw in the Cold War.

U-2 Incident

The Russians shot down a high-altitude US spy plane, the U-2, over the Soviet Union. The incident exposed a secret U.S. tactic for gaining information. After the open skies proposals had been rejected by the Soviets, the U.S. decided to conduct regular spy flights over Soviet territory to find out about its enemy’s missile program.

Eisenhower took full responsibility for the flights AFTER they were exposed by the U-2 incident, but his honesty proved to be a diplomatic mistake. Khrushchev, the secretary of the USSR, denounced the U.S. and walked out of the Paris summit to temporarily end the thaw in the Cold War.

Communism in Cuba

Fidel Castro overthrew the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959. Once in power, Castro nationalized American-owned businesses and properties in Cuba. Eisenhower retaliated by cutting off U.S. trade with Cuba.

Castro then turned to the Soviets for support. He revealed that he was a Marxist and soon proved it by setting up a Communist totalitarian state. With communism only 90 miles off the shores of Florida, Eisenhower authorized the CIA to train anti-communist Cuban exiles to retake their land, but the decision to go ahead was left up to the next president, Kennedy.

Bay of Pigs Invasion

Kennedy made a major blunder shortly after entering office. He approved a Central Intelligence Agency scheme planned under Eisenhower to use Cuban exiles to overthrow Fidel Castro’s regime in Cuba. In April of 1961, 1400 Cuban exiles moved ashore at the Bay of Pigs on the southern coast of Cuba. They failed to set off a general uprising as planned. Castro’s forces had air superiority and had no difficulty quashing the invasion. They killed nearly 500 exiles and the rest surrendered. Kennedy was shocked by the swiftness of the defeat and took personal responsibility for the Bay of Pigs.

Kennedy and Berlin

A steady flight of skilled workers to the West through the Berlin escape route weakened the East German regime dangerously. The Soviets sealed off their zone of the city. They began the construction of the Berlin Wall to stop the flow of brains and talent to the West. Russian and American tanks maneuvered within sight of each other at Checkpoint Charlie (where the two zones met).

On July 25, Kennedy delivered an impassioned televised address to the American people in which he called the defense of Berlin essential to the entire Free World. To cheering crowds, he proclaimed “Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put up a wall to keep our people in…as a free man, I take pride in the words. Ich bin ein Berliner (I am a Berliner)."

Cuban Missile Crisis

Throughout the summer and early fall of 1962, the Soviets engaged in a massive arms buildup in Cuba, to protect Cuba from American invasion. Kennedy issued a stern warning against any offensive weapons in Cuba. Secretly, Khrushchev was building sites for 24 medium-range (1000 mile) and 18 intermediate-range (2000 mile) missiles in Cuba. He later claimed his purpose was purely defensive, but most likely he was responding to the pressures from his own military to close the enormous strategic gap in nuclear striking power.

Image Courtesy of Smithsonian Magazine

Kennedy allowed U-2 flights over Cuba. The first mission brought back indisputable photographic evidence of the missile sites, which were nearing completion. Kennedy decided to keep the information secret while he consulted with a hand-picked group of advisers to consider how to respond, a group that would become known as ExComm.

Kennedy agreed to a two-step procedure:

- He would proclaim a quarantine of Cuba to prevent the arrival of new missiles.

- He would threaten a nuclear confrontation to force the removal of those already there. On the evening of October 22, the president informed the nation of the existence of the Soviet missiles and his plans to remove them. For the next 6 days, the world hovered on the brink of nuclear war.

In the Atlantic, 16 Soviet ships continued on course towards Cuba, while the American navy was deployed to intercept them 500 miles from the island.

Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles in return for Kennedy’s promise not to invade Cuba and to later remove some U.S. missiles from Turkey. The crisis was over. Shaken by their close call, Kennedy and Khrushchev agreed to install a “hotline” to speed direct communication between Washington and Moscow in an emergency.

Détente

Nixon and Kissinger strengthened the US position in the world by taking advantage of the rivalry between the two Communist giants, China and the Soviet Union. Their diplomacy was praised for bringing about détente—a deliberate reduction of Cold War tensions.

Nixon planned to use American trade, notably grain and high technology, to induce Soviet cooperation, while at the same time improving U.S.-China relations. In 1972, Nixon visited China, meeting with the Communist leaders and ending more than two decades of Sino-American hostility.

He agreed to establish an American liaison mission in Beijing as the first step toward diplomatic recognition. The Soviets, who viewed China as a dangerous adversary, responded by agreeing to an arms control pact with the United States.

Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) had been underway since 1969. During a visit to Moscow in 1972, Nixon signed two vital documents with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. This would be known as SALT I:

- The first limited the two superpowers to two hundred antiballistic missiles apiece.

- The second froze the number of ballistic missiles for a 5-year period. This was the most important first step toward control of the nuclear arms race.

Carter and the Cold War

Carter signed the SALT II treaty with the Soviet Union in 1979, which provided for limiting the size of each superpower’s nuclear delivery system. The Senate never ratified the treaty.

The Cold War resumed with full fury when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979. The U.S. feared that the invasion might lead to a Soviet move to control the oil-rich Persian Gulf.

Carter reacted by issuing what became known as the Carter Doctrine which:

- halting grain exports and high technology to the Soviet Union

- and boycotting the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.