Browse By Unit

Theme 4 (MIG) - Migration and Settlement

22 min read•june 18, 2024

nicole-donawho

nicole-donawho

The one thing you need to know about this theme:

| Causation and Migration

| Humans do not uproot themselves without cause. Likewise, the movement of people across space and over time does not occur without consequence. The displacement of small and large groups of people always has a catalyst, and is always followed by some kind of social, political, environmental, or other type of change to their new surroundings. |

College Board Description📘

This theme focuses on why and how the various people who moved to and within the United States both adapted to and transformed their new social and physical environments.

Organizing Question🔎

What push and pull factors influence immigration and migration patterns, and how do these moves change the society and culture of the migrants’ new home?

Key Vocabulary📝

| Encomienda System | Caste System | Powhatan Wars | Puritan-Pequot War |

| Metacom's War | Walking Purchase of 1737 | Pontiac's Rebellion | Proclamation of 1763 |

| Paxton Boys | Regulators | Northwest Ordinance of 1787 | Treaty of Greenville |

| Push vs. Pull Factors | "Old" + "New" Immigration | Transcontinental Railroad | Transatlantic Telegraph Cable |

| The Grange | Colored Farmers' Alliance | Munn v. Illinois (1787) | Treaty of Fort Laramie |

| Sand Creek Massacre | Fetterman Massacre | Indian Appropriation Act | Wounded Knee Massacre |

| Assimilation | Dawes Act | Carlisle Indian School | Tenements |

| Social Darwinism | Settlement Houses | Nativism | Red Scare |

| Schenck v. United States (1919) | Chinese Exclusion Act | Quota System | Great Migration |

| Red Summer | Levittowns | Sun Belt | Immigration Reform and Control Act |

Historical Examples of this Theme:

Period 1 (1491-1607)

In this early era, the focus is primarily on pre-British exploration and settlement of the Americas. The year 1491 signifies anything that occurred in the years before Columbus’ “discovery” of the New World. This includes the numerous Native American tribes and cultures that existed in the Americas before European exploration.

Native American Tribes

The most critical knowledge for students to have of this pre-Columbian period will be the general cultural and economic traits of tribes by regional settlement, as well as an example of at least one tribe from each region.

| Northeast | In the Northeast, tribes like the Iroquois thrived on a mixed economy of hunting and farming. As a strongly matriarchal society, Iroquois women mostly tended to community affairs while men hunted. |

| Mississippi River Valley | The Mississippi River Valley, home to tribes like the Cahokia, could sustain large and complex societies through agriculture provided by the Mississippi River’s rich sediment deposits. These tribes are also sometimes known as the Mississippi Mound Builders for their large earthen mounds in a variety of shapes and sizes. |

| Southwest | In the arid Southwest, tribes used a complex system of underground irrigation to provide water for farming. Tribes like the Zuni and Anasazi lived in multi-family dwellings made of clay, which the Spanish called “pueblos,” meaning “village.” |

| Northwest | Native Americans in the Northwest practiced hunting and gathering as well as foraging for wild nuts and berries. Tribes like the Chinooks lived in multi-family dwellings called longhouses. |

European Arrival in America

When Europeans came to the Americas, they did so for three main reasons: Gold, Glory, and God. Many of the Spanish conquistadors (conquerors) who ventured to the New World in the sixteenth century did so out of necessity due to laws of primogeniture, where the first born son inherited the family estate. Second and third sons of wealthy families who inherited nothing could either turn to the priesthood or find their way to wealth.

European nations also did not want to come last in the increasingly intense race across the planet. After the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), Portugal claimed a solid foothold along the western coast of Africa, and Spain sent increasing numbers of settlers to South American silver mining and agricultural colonies. And as events in Europe unfurled, like the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, claims to colonial territories thousands of miles away gained strategic political significance.

Of course, Europeans also migrated to the Americas in the hopes of Christianizing the Native tribes. Priests out of Spain and France set up missions in different parts of the New World with often drastically different methods of conversion and varying levels of success.

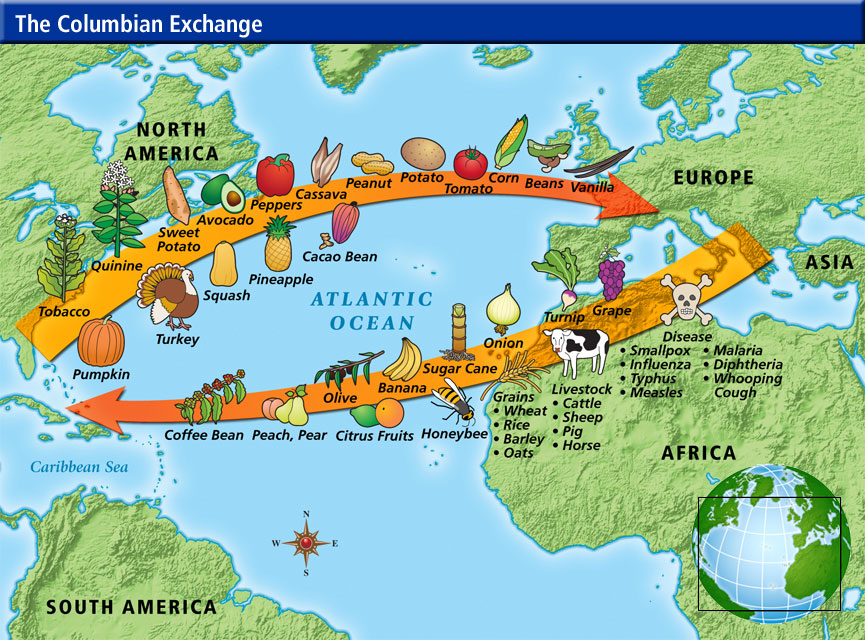

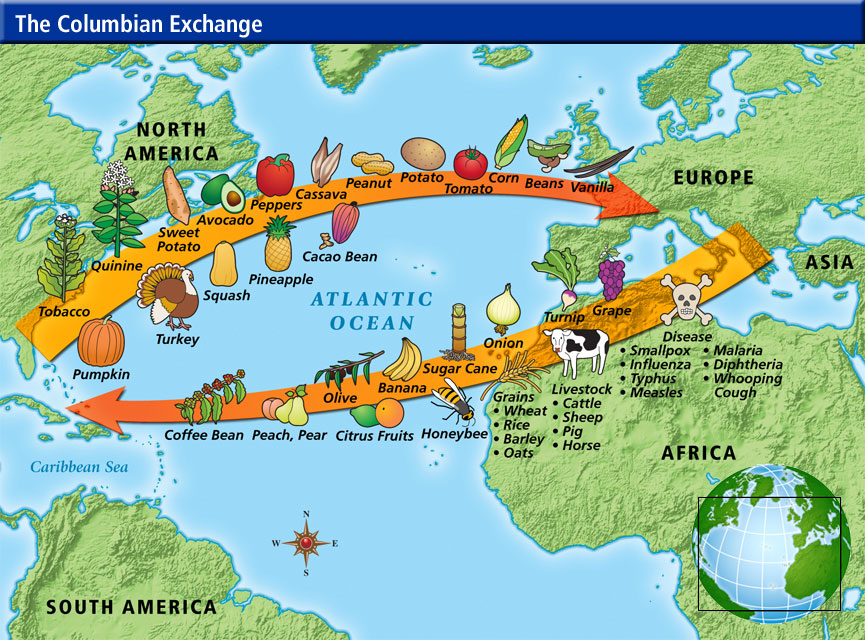

One of the most significant effects of European settlement of the Americas was the Columbian Exchange. In addition to providing new food and technological items to both Native and European populations, interactions among the two populations introduced new diseases to people without immunity. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Native Americans died from diseases like smallpox.

Image Courtesy of Khan Academy

Period 2 (1607-1754)

Whereas Period 1 (1491-1607) focuses mostly on why Europeans migrated to the New World, Period 2 (1607-1754) is primarily concerned with where and why they settled. The curriculum framework singles out four European nations with varying levels of attention: the Spanish, French, Dutch, and English.

Spain in the New World

Spain’s settled areas of the Americas that the crown could use for profit, like mining or agriculture. In doing so, Spaniards mixed their priorities of Christianizing the Native populations with their need for labor. In the encomienda system, Spanish landowners required Natives to work and pay tribute in exchange for protection. Catholic priests used the proximity of Natives to teach them about Christianity. This system, however, quickly turned into a form of forced labor and was replaced by another called the repartimiento system.

The Spanish also divided their society into a rigid caste system based on race. At the top of this social hierarchy were peninsulares - individuals who migrated directly from the Iberian Peninsula. Directly below the peninsulares were their children, who were still considered entirely white, but less authoritative due to their birth in the Americas. Beneath this class of fully white people was the mestizos, or children of one white Spaniard and one Native American. The bottom of the hierarchy consisted of Native Americans and enslaved or freed Africans.

Image Courtesy of Redborne Nation

The Spanish practice of subjugating Native Americans into economic and social systems of oppression served their purposes of settlement - to extract wealth from their surroundings and spread Christianity. By turning non-white peoples into a productive labor force, colonial Spaniards were able to prove the might of their empire with shiploads of precious metals and agricultural goods. And the creation of a system whereby Native Americans were in constant proximity with Spanish priests and churches facilitated the conversion, genuine or not, of at least some of that population.

The French + Dutch in the New World

The French and Dutch used a strategically different approach than the Spanish in achieving their economic goals in the Americas. Neither European power dedicated large numbers of people to settle their American colonies, and both focused primarily on commercial partnerships.

The Dutch settlement of New Netherland, for example, was the center of a lucrative fur trade and the epicenter of trade for various colonies along the eastern seaboard until it was taken over by the British in 1664. The Dutch did not have to supply large numbers of their people for this colony, though. Favorable trade relationships with Native Americans and rules of self-governance and civil rights for women encouraged migration to the colony from across Europe.

French fur traders in the Great Lakes region also sought positive trade relationships with Native Americans, sometimes marrying into native tribes to create alliances and build diplomatic relations. Additionally, Jesuit missionaries who came to the Americas often lived among the Huron tribes they hoped to convert. Because of the sometimes transient nature of these lifestyles, early French migration to the Americas was overwhelmingly male and relatively small when compared to the more permanent settlement of other European nations.

The 13 Colonies - Regions

The settlement and expansion of the original thirteen British colonies are significant because the narrative of the United States History grows out of their establishment. It is most helpful to break these colonies into their respective geographic regions, as this is how an essay question will most likely address comparison between them. Students should know which colonies fall into these regions, as well as their basic economic, political, and social structures.

| Chesapeake Colonies | The Chesapeake consisted of Virginia and Maryland. The region originated in 1607, with the settlement of Jamestown by the Virginia Company. After a rough period called the “Starving Time,” settlers learned to grow tobacco as a cash crop successfully. In 1619, the House of Burgesses became the first representative government established in the British colonies. However, the same year also saw the first introduction of African slavery to the British colonies, which would eventually replace the system of indentured servitude as a labor source. |

| New England | The New England colonies were New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. The early settlers of Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colony, Puritans and Pilgrims, settled the region to escape religious persecution in England. Originally establishing societies based on subsistence farming, the economies of New England’s colonies eventually grew to include shipping and trade.In the strictly-controlled religious community of Massachusetts Bay Colony, only male church members could vote. Over time, this came to include more male members of the community with actions like the Half-Way Covenant but was still strictly tied to religious involvement. Rhode Island, however, practiced separation of church and state. Their charter promising self-governance extended suffrage to more individuals than any other colony at the time. |

| Middle Colonies | Pennsylvania, Delaware, New York, and New Jersey comprised the Middle Colonies. The governments of these colonies were usually proprietary. This means that after receiving a land grant from the king, a company or person selected an official or administrator to govern the colony. The economies of the Middle Colonies were a diverse mixture of agriculture, shipbuilding, and logging. This rich economic base and tolerant societies of colonies like Pennsylvania attracted migrants from surrounding regions and immigrants from Europe like the Scots-Irish. |

| Southern Colonies | North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia made up the Southern colonies. The economies of the South depended on cash crops like rice and indigo. Unlike the Chesapeake, the South did not use indentured servants for labor; they depended solely on the use of African slaves. All colonial governments in the South elected their own legislatures but were royal colonies governed directly by the crown’s governor. |

Conflict with Native Americans

All thirteen British colonies encountered conflict with Native Americans at some point, often as a result of encroaching and expanding onto Native lands. The settlement of Jamestown in the middle of the Powhatan Confederacy led to the First and Second Powhatan Wars, ending in 1646 with a treaty that removed the Powhatans from much of their original lands. In 1676, Bacon’s Rebellion began due to conflicts with former indentured servants and Native Americans on the western borders of Virginian society.

The Puritan-Pequot War (1637-1638) that led to the massacre of roughly 500 Pequot men, women, and children led the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony to believe that their success was a sign of God’s favor. This led to further expansion and, ultimately, Metacom’s War (1675-1678), which ended with massive casualties for both sides. But violence wasn’t even always necessary. In Pennsylvania, the Walking Purchase of 1737 swindled the Delaware tribe out of roughly 1,200 acres of land at the hands of William Penn’s son.

Ultimately, the men and women who migrated to the thirteen British colonies did so for a variety of economic, social, and religious reasons. The settlements they created varied in structure but held the commonality that they were working within a mercantilist economy. They also all had conflicts with Native Americans over land and cultural differences, which impacted decisions and policies for expansion for decades.

**Quick Tip: Native American history surrounds local schools across the United States. Students should work with their teachers and local historical societies to learn more about these local tribes, and how migration and settlement patterns affected their sustainability and development.

Period 3 (1754-1800)

After the French and Indian War, the British claimed land in the Americas extending West of the Appalachian Mountains. Native tribes like the Iroquois, who sided with the British during the war, largely rejected these claims. Nevertheless, mixtures of violence and bribes led to decreased tribal lands.

Post French and Indian War

In 1763, Pontiac’s Rebellion in the Ohio River Valley led the British government to institute Proclamation of 1763, which forbid westward expansion West of the Appalachian Mountains. Colonists who saw access to property as fundamental freedom decried the proclamation as an infringement of their rights as Englishmen. Others, like the Scots-Irish Paxton Boys, exacted their revenge against Native Americans when they felt that colonial governments did not do enough to protect them.

Some settlers also felt a sense of deepening economic and social division associated with westward migration. In the mid-eighteenth century, a group of North Carolina vigilante rebels called the Regulators fought against corruption in their colonial government. The Regulators argued that despite living on less valuable “frontier” land, officials taxed them at the same levels as those living on fertile coastal land. They also complained that despite paying these excessive taxes, the government did little to protect them.

Following the American Revolution, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 created a Northwest Territory and provided a means of admitting new states to the Union from that territory. Like the decades before, this government declaration stood in contrast with Native American claims to the same land. In 1794, the Battle of Fallen Timbers and subsequent Treaty of Greenville (1795) secured the hotly-contested Ohio River Valley for the United States. In the treaty, the United States acknowledged Native American ownership of Ohio, and therefore paid them for it; in exchange, Native Americans accepted American sovereignty.

Despite the end of the American Revolution with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, British soldiers remained in the American West during the late eighteenth century. These soldiers repeatedly worked with Native American tribes against the new United States government, including providing weapons for attacks. Despite stipulations in Jay’s Treaty (1794) that this collusion end, tensions between the United States and Britain continued to increase, ultimately leading to war.

Period 4 (1800-1848)

Immigration

College Board does not explicitly attach the theme of migration and settlement to this period in the curriculum framework. Still, the Market Revolution does include one major immigrant movement that is important to know.

From roughly the 1820s to the 1840s, Irish and German immigrants made their way to the United States as part of “Old” immigration. This is often juxtaposed with “New” immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans in the Gilded Age (1865-1898).

For Irish immigrants, the biggest push factor was the Irish potato famine, in which roughly one million people died of starvation. German immigrants came in search of religious and political freedom.

For both groups, the pull factor was economic opportunity. Irish immigrants worked as both farmers and industrial workers in cities like New York and Chicago. German immigrants usually settled in farming areas of the North and Midwest, like Pennsylvania.

**Quick Tip: One of the most important things to understand when it comes to migration and settlement is the push and pull factors that lead people to move from one place to another. Learning the common push and pull factors across time can help make the types of connections necessary for getting the second “analysis and reasoning” point on the DBQ and LEQ. A Short Answer Question could also ask you to provide a push/pull factor during one period in part “a” and a similar push/pull factor in another period in part “b” (for example).

Period 5 (1844-1877)

While Period 5 addresses Manifest Destiny from the political perspective of increased sectionalism, the exam does not address this theme concerning migration and settlement until Period 6.

Period 6 (1865-1898)

Movements in migration and settlement during this period center around two main trends: westward migration following the Civil War and the growth of urbanization.

Westward Migration + Technology

The causes of westward migration following the Civil War were due largely to improved technology in farming and transportation. Some of these improvements, like the steel plow and mechanical reaper, originated in the early nineteenth century and continued to increase agricultural production. Other inventions, like barbed wire, revolutionized the way farmers separated and protected property.

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad was critical to the settlement of the West after the Civil War. The railroad not only bridged existing systems of the east with the Pacific coast but opened new markets in the West along the tracks’ route. As additional expansions to the original line unfolded, manufacturers in the east could count on farmers in the West to purchase their goods and vice versa.

Transportation was not the only new technology to revolutionize markets. The installation of the transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866 made it possible to communicate in a matter of seconds information that formerly took weeks to carry in ships across the Atlantic. Farmers and businessmen could receive updated values for goods and currency in real-time, making the practice of doing business more efficient.

Farmers

With increased efficiency in agriculture and business came problems for farmers. As farming prices became more efficient, food prices decreased. At the same time, ruthless business practices and government favor in the railroad industry led to the consolidation of that market in the face of increasing agricultural dependence on rail lines.

In the face of these problems, farmers created regional cooperative organizations like the Grange and the Colored Farmers’ Alliance. The primary function of groups like these was to collectively fight against the monopolistic powers of the railroad and grain elevator industries. In 1877, they had some success in the case of Munn v. Illinois, which ruled that state governments can regulate private businesses that serve public interests.

New modes of transportation moved thousands of migrants to the American West in the years between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the century. This movement was bolstered by innovations to help migrants become successful and community organizations that lent a voice to their growing concerns. The biggest effect of this migration, however, was not groundbreaking or inventive.

Land Disputes with Native Americans

Massive westward movement into the Great Plains after the Homestead Act (1862) led to disputes over land claimed by the Plains Indians - tribes like the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Osage. White settlers attempted to rid the Great Plains of Native Americans by killing their food source, the American bison, almost to extinction. When that did not work, the United States government resorted to violence.

When it comes to the AP exam, there are several terms involving the United States government and Union Army that are helpful to know as examples for this period.

| Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851) | This treaty set defined boundaries for Native American territory in the Great Plains. In exchange for allowing settlers and railroad workers to travel safely through tribal lands, the United States government was supposed to deliver resources to tribes. |

| Sand Creek Massacre (1864) | The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes were granted land by the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851), but gold-seekers and settlers violated that land. After making a new arrangement with the government, Black Kettle moved his band of Cheyenne to Sand Creek to hunt. U.S. Cavalry troops led an attack on them, killing 148 Native Americans - over half of them women and children. |

| Fetterman Massacre (1866) | In response to the Sand Creek Massacre, Native Americans across the Great Plains began attacking white settlers. The United States government began building forts along trails in the Black Hills, Sioux territory, to protect settlers. In 1866, Red Cloud and Crazy Horse led an attack against Captain William Fetterman and his men at Fort Phil Kearney, successfully defeating them. It was a clear victory for the Native Americans but led to treaties with smaller reservations and less government support. |

| Indian Appropriation Act (1871) | This law ended the ability of Native American tribes to make treaties with the United States government. |

| Battle of Little Bighorn (1876) | When white settlers discovered gold in the Black Hills, the United States government forced the Lakota Sioux to move from their ancestral lands. Some of the tribes missed the deadline for moving, so the federal government dispatched Lieutenant Colonel George Custer and the 7th Cavalry to confront them. Custer and his men were quickly overwhelmed by Sitting Bull and his men, and were defeated in what is often called “Custer’s Last Stand.” |

| Wounded Knee Massacre (1890) | After the killing of Sitting Bull and other followers of the Ghost Dance movement, the 7th Cavalry went to disarm a band of Sioux at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. In their attempt, a shot went off, and chaos ensued. The 7th Cavalry opened fire on the Sioux and massacred more than 200 men, women, and children. |

As violent action against Native Americans continued to unfold, the United States government increasingly promoted assimilationist policies. In 1881, poet and novelist Helen Hunt Jackson wrote A Century of Dishonor, in which she laid out the federal government’s atrocities against Native tribes over the previous hundred years. Despite some criticism, Congress appointed a special commission to look into her claims, ultimately leading to the Dawes Act of 1887.

The Dawes Act (or Dawes Severalty Act) allowed the federal government to divide reservation lands into individual plots of 160 acres for heads of family, or less for individuals. Those who accepted the land were granted United States citizenship, but could not legally own the land until after 25 years.

In addition to the Dawes Act, boarding schools like the Carlisle Indian School sought to assimilate Native American children into American culture by teaching them how to speak, dress, eat, and pray like white people. Such schools were notorious for their tactics of physically abusing children for speaking their native tongue, separating siblings from each other in gender-segregated environments, and forcing children to work long hours when not in class.

Both the Dawes Act and schools like Carlisle Indian School hoped to assimilate Native Americans into white culture by eliminating critical aspects of tribal identity - communal living and farming, native languages, gender equity in work, and religious traditions. For some tribes, the combination of violent warfare, starvation, and assimilation of their youngest generation did wipe out entire histories stretching thousands of years. Others, however, managed to hold on to tribal identities despite assimilationist policies and attempted to develop self-sustaining economic practices.

Population Boom

As farmers, ranchers, and miners moved West after the Civil War, a similar population boom occurred in urban centers east of the Mississippi River. At the start of the Civil War, the population of New York City was just over one million people. By 1880, that number had almost doubled due to immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.

In this period, Southern and Eastern Europeans left their homes (push factors) due to limited social mobility and poverty, as well as religious persecution. They came to the United States (pull factors) for industrial jobs. It is important to know that the pull factor for almost all immigrants to the United States is jobs. Knowing what kinds of jobs immigrants are working and where during each period will make it easy to plug that information in when necessary.

Ethnic Enclaves

Upon arriving in the United States, immigrants tended to settle into ethnic communities like “Chinatown” and “Little Italy.” This was practical, in a sense, because the new surroundings drew people to familiarity - those who spoke the same language, attended the same churches, and shopped in the same markets. However, the ethnic communities also existed because white Americans economically and socially prevented immigrants from moving into their parts of the city.

Immigrants

Immigrants often lived in buildings called tenements. These multi-story dwellings held concentrated numbers of people and often faced issues with sanitation and safety. Upper-class white individuals had little sympathy for the problems faced by those in the poorer parts of the city. Subscribing to a theory later called Social Darwinism, wealthy Americans saw inequality as an inevitable outcome of capitalism. Accordingly, those who lived in poverty did so because they were somehow inherently inferior.

In line with this logic, white Americans promoted the same agenda of assimilationist policies to immigrants as they did to Native Americans. Whites expected immigrants to abandon their home language in favor of English and adopt American food and dress. Social advocates like Jane Addams in Chicago set up settlement houses with the ultimate goal of helping immigrant women and children with the transition to American language and customs.

Just as the immigrant groups before them, Gilded Age immigrants made compromises in what they adopted and abandoned. Food was particularly permeable into American culture. For example, hamburgers, bratwursts (and other sausages), and sauerkraut all made their way into dominant culture as popular foods that were once exclusively found in German communities.

Westward expansion and urbanization both led to population growth in the years following the American Civil War. In both instances, the groups most affected by this growth - Native Americans and immigrants - faced challenges to their identities and stereotypes of inferiority. Meanwhile, white Americans capitalized on their wealth and influence to further their own political, social, and economic goals.

Period 7 (1890-1945)

Period 7 is one of the most extensive (in terms of events covered) in the timeline. It covers the Spanish American War, World War I, the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, the New Deal, and World War II. Migration and settlement during the period center on the movement of people during and as a result of wars.

The Rise of Communism

In 1917, the outbreak of the Bolshevik Revolution and subsequent United States involvement in World War I significantly changed the way Americans and the federal government treated immigrants. While the United States had always practiced nativism, a preference for native-born citizens and dislike of immigrants, anxiety over the spread of Communism led to widespread attacks on immigrant culture during World War I.

This widespread fear, called the Red Scare, led to restrictions on the First Amendment and attacks on labor activism. The case Schenck v. United States (1919) upheld the Espionage Act (1917), which made it a crime to undermine the United States or the armed forces during a war or aid the nation’s enemies. The federal government put its support behind “open shop” businesses, which did not require workers to join labor unions as conditions of employment.

The federal government also took steps to cut back immigration through new immigration laws. This began with the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which barred all immigration from China and was the nation’s first national immigration policy. In the 1920s, the United States adopted a quota system to handle immigrants from European nations. The government would determine the number of immigrants allowed into the United States from a European country as two percent of the number of people from that country living in the United States as of the 1890 census.

Migration in the US

Despite this cutback on immigration, urban centers continued to serve as a center of economic opportunity for millions of individuals. During World War I and World War II, many African Americans migrated from the rural South to the North and West (during World War II) to fill critical industrial jobs in the Great Migration.

African Americans leaving the Jim Crow South did so to escape violence, segregation, and limited economic opportunity. While cities in the North and West offered a reprieve from some of these issues, they were not without fault. In what is now called the Red Summer of 1919, black and white communities clashed in a series of violent race riots across the nation.

Urban areas also provided opportunities for women to escape their traditional economic roles. Women in the city worked as telephone operators, in department stores, and as secretaries. During both World War I and World War II, women readily filled vacant industrial jobs - a compelling cause for the 19th Amendment (1920). City life also gave women a new sense of independence and agency over their bodies, occupations, and futures.

Migration and settlement causes and effects during and after times of war vary dramatically depending on which side of the war a group is on. For those considered to be on the “good” side, the increased economic production associated with World War I and World War II led to tangible benefits. For those on the “bad” side, the stigma of negativity permeated all aspects of political, economic, and social life.

Period 8 (1945-1980)

Following World War II, the Servicemen's Readjustment Act (1944) - also known as the G.I. Bill - provided college tuition, low-interest home loans, and medical treatment for returning soldiers. Additionally, new medical technology, like penicillin and the polio vaccine, as well as innovations in child-rearing and development from perceived experts like Dr. Benjamin Spock, contributed to a baby boom.

To house their new families, white middle-class families moved to the suburbs. Dotted with prefabricated homes, these neighborhoods - often called Levittowns after real estate developer William Levitt - provided a clean and insulated environment for families to raise their children. Because mortgage agreements often forbid the sale or resale of homes to African Americans, the suburbs also guaranteed a type of segregation that the city could not.

A region of new development, spanning roughly from the Carolinas to California, was referred to as the Sun Belt for its generally warm climate and access to air conditioning. In contrast, the quickly dilapidated cities left behind by the exodus of white migrants became known as the Rust Belt. Formerly boisterous cities like Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and Detroit fell to ruins as large numbers of their tax base left for southern towns.

As people within the United States moved, immigrants from around the world sought new opportunities in the United States. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson passed a new immigration reform law that removed the quota systems in place since the 1920s. Holding a signing ceremony on Liberty Island under the Statue of Liberty, government officials hailed the new bill as a triumph of progress for American immigration policy. However, at the same time that the bill removed the old quota system, it set in place language limiting immigration from Central and South America.

Period 9 (1980-present)

During the Cold War, increasing population shifts to the Sun Belt and American West led to tremendous political and social influence in those regions. This trend is most noticeable in the election of “Sun Belt presidents” like Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan (elected at the start of this time period), George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George H.W. Bush.

Having presidents from the Sun Belt for the majority of this period has given that area a tremendous amount of power in the United States. The president’s agenda controls not only political aspects of American society, but social and economic issues as well - education reform, energy sources, and foreign policy.

As the United States crawled out of the economic recession that plagued much of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, the federal government took steps to ensure the safety of American jobs. The Immigration Reform and Control Act (1986) prohibited employers from hiring unauthorized immigrant workers for either temporary or permanent jobs. This reform bill most heavily impacted states in the South and West, which held the highest concentrations of immigrant populations from Central and Southern America and Asia.

Sample Questions

Sample SAQ✏️

| Rural and Urban Populations of the United States, 1860-1900 |

| Year |

| 1860 |

| 1870 |

| 1880 |

| 1890 |

| 1900 |

Source: United States Census Bureau.

Using your knowledge of United States History and the chart above, answer the following in complete sentences.

- Identify one specific cause of change for the rural population from 1860 to 1900.

- Identify one specific cause of change for the urban population from 1860 to 1900.

- Explain one way that a historical development in either the rural or urban region affected population change in the opposite region from 1860 to 1890.

Sample LEQ✏️

Evaluate the extent to which political and economic developments encouraged the settlement of the West from 1877 to 1898.

<< Hide Menu

Theme 4 (MIG) - Migration and Settlement

22 min read•june 18, 2024

nicole-donawho

nicole-donawho

The one thing you need to know about this theme:

| Causation and Migration

| Humans do not uproot themselves without cause. Likewise, the movement of people across space and over time does not occur without consequence. The displacement of small and large groups of people always has a catalyst, and is always followed by some kind of social, political, environmental, or other type of change to their new surroundings. |

College Board Description📘

This theme focuses on why and how the various people who moved to and within the United States both adapted to and transformed their new social and physical environments.

Organizing Question🔎

What push and pull factors influence immigration and migration patterns, and how do these moves change the society and culture of the migrants’ new home?

Key Vocabulary📝

| Encomienda System | Caste System | Powhatan Wars | Puritan-Pequot War |

| Metacom's War | Walking Purchase of 1737 | Pontiac's Rebellion | Proclamation of 1763 |

| Paxton Boys | Regulators | Northwest Ordinance of 1787 | Treaty of Greenville |

| Push vs. Pull Factors | "Old" + "New" Immigration | Transcontinental Railroad | Transatlantic Telegraph Cable |

| The Grange | Colored Farmers' Alliance | Munn v. Illinois (1787) | Treaty of Fort Laramie |

| Sand Creek Massacre | Fetterman Massacre | Indian Appropriation Act | Wounded Knee Massacre |

| Assimilation | Dawes Act | Carlisle Indian School | Tenements |

| Social Darwinism | Settlement Houses | Nativism | Red Scare |

| Schenck v. United States (1919) | Chinese Exclusion Act | Quota System | Great Migration |

| Red Summer | Levittowns | Sun Belt | Immigration Reform and Control Act |

Historical Examples of this Theme:

Period 1 (1491-1607)

In this early era, the focus is primarily on pre-British exploration and settlement of the Americas. The year 1491 signifies anything that occurred in the years before Columbus’ “discovery” of the New World. This includes the numerous Native American tribes and cultures that existed in the Americas before European exploration.

Native American Tribes

The most critical knowledge for students to have of this pre-Columbian period will be the general cultural and economic traits of tribes by regional settlement, as well as an example of at least one tribe from each region.

| Northeast | In the Northeast, tribes like the Iroquois thrived on a mixed economy of hunting and farming. As a strongly matriarchal society, Iroquois women mostly tended to community affairs while men hunted. |

| Mississippi River Valley | The Mississippi River Valley, home to tribes like the Cahokia, could sustain large and complex societies through agriculture provided by the Mississippi River’s rich sediment deposits. These tribes are also sometimes known as the Mississippi Mound Builders for their large earthen mounds in a variety of shapes and sizes. |

| Southwest | In the arid Southwest, tribes used a complex system of underground irrigation to provide water for farming. Tribes like the Zuni and Anasazi lived in multi-family dwellings made of clay, which the Spanish called “pueblos,” meaning “village.” |

| Northwest | Native Americans in the Northwest practiced hunting and gathering as well as foraging for wild nuts and berries. Tribes like the Chinooks lived in multi-family dwellings called longhouses. |

European Arrival in America

When Europeans came to the Americas, they did so for three main reasons: Gold, Glory, and God. Many of the Spanish conquistadors (conquerors) who ventured to the New World in the sixteenth century did so out of necessity due to laws of primogeniture, where the first born son inherited the family estate. Second and third sons of wealthy families who inherited nothing could either turn to the priesthood or find their way to wealth.

European nations also did not want to come last in the increasingly intense race across the planet. After the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), Portugal claimed a solid foothold along the western coast of Africa, and Spain sent increasing numbers of settlers to South American silver mining and agricultural colonies. And as events in Europe unfurled, like the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, claims to colonial territories thousands of miles away gained strategic political significance.

Of course, Europeans also migrated to the Americas in the hopes of Christianizing the Native tribes. Priests out of Spain and France set up missions in different parts of the New World with often drastically different methods of conversion and varying levels of success.

One of the most significant effects of European settlement of the Americas was the Columbian Exchange. In addition to providing new food and technological items to both Native and European populations, interactions among the two populations introduced new diseases to people without immunity. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Native Americans died from diseases like smallpox.

Image Courtesy of Khan Academy

Period 2 (1607-1754)

Whereas Period 1 (1491-1607) focuses mostly on why Europeans migrated to the New World, Period 2 (1607-1754) is primarily concerned with where and why they settled. The curriculum framework singles out four European nations with varying levels of attention: the Spanish, French, Dutch, and English.

Spain in the New World

Spain’s settled areas of the Americas that the crown could use for profit, like mining or agriculture. In doing so, Spaniards mixed their priorities of Christianizing the Native populations with their need for labor. In the encomienda system, Spanish landowners required Natives to work and pay tribute in exchange for protection. Catholic priests used the proximity of Natives to teach them about Christianity. This system, however, quickly turned into a form of forced labor and was replaced by another called the repartimiento system.

The Spanish also divided their society into a rigid caste system based on race. At the top of this social hierarchy were peninsulares - individuals who migrated directly from the Iberian Peninsula. Directly below the peninsulares were their children, who were still considered entirely white, but less authoritative due to their birth in the Americas. Beneath this class of fully white people was the mestizos, or children of one white Spaniard and one Native American. The bottom of the hierarchy consisted of Native Americans and enslaved or freed Africans.

Image Courtesy of Redborne Nation

The Spanish practice of subjugating Native Americans into economic and social systems of oppression served their purposes of settlement - to extract wealth from their surroundings and spread Christianity. By turning non-white peoples into a productive labor force, colonial Spaniards were able to prove the might of their empire with shiploads of precious metals and agricultural goods. And the creation of a system whereby Native Americans were in constant proximity with Spanish priests and churches facilitated the conversion, genuine or not, of at least some of that population.

The French + Dutch in the New World

The French and Dutch used a strategically different approach than the Spanish in achieving their economic goals in the Americas. Neither European power dedicated large numbers of people to settle their American colonies, and both focused primarily on commercial partnerships.

The Dutch settlement of New Netherland, for example, was the center of a lucrative fur trade and the epicenter of trade for various colonies along the eastern seaboard until it was taken over by the British in 1664. The Dutch did not have to supply large numbers of their people for this colony, though. Favorable trade relationships with Native Americans and rules of self-governance and civil rights for women encouraged migration to the colony from across Europe.

French fur traders in the Great Lakes region also sought positive trade relationships with Native Americans, sometimes marrying into native tribes to create alliances and build diplomatic relations. Additionally, Jesuit missionaries who came to the Americas often lived among the Huron tribes they hoped to convert. Because of the sometimes transient nature of these lifestyles, early French migration to the Americas was overwhelmingly male and relatively small when compared to the more permanent settlement of other European nations.

The 13 Colonies - Regions

The settlement and expansion of the original thirteen British colonies are significant because the narrative of the United States History grows out of their establishment. It is most helpful to break these colonies into their respective geographic regions, as this is how an essay question will most likely address comparison between them. Students should know which colonies fall into these regions, as well as their basic economic, political, and social structures.

| Chesapeake Colonies | The Chesapeake consisted of Virginia and Maryland. The region originated in 1607, with the settlement of Jamestown by the Virginia Company. After a rough period called the “Starving Time,” settlers learned to grow tobacco as a cash crop successfully. In 1619, the House of Burgesses became the first representative government established in the British colonies. However, the same year also saw the first introduction of African slavery to the British colonies, which would eventually replace the system of indentured servitude as a labor source. |

| New England | The New England colonies were New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. The early settlers of Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colony, Puritans and Pilgrims, settled the region to escape religious persecution in England. Originally establishing societies based on subsistence farming, the economies of New England’s colonies eventually grew to include shipping and trade.In the strictly-controlled religious community of Massachusetts Bay Colony, only male church members could vote. Over time, this came to include more male members of the community with actions like the Half-Way Covenant but was still strictly tied to religious involvement. Rhode Island, however, practiced separation of church and state. Their charter promising self-governance extended suffrage to more individuals than any other colony at the time. |

| Middle Colonies | Pennsylvania, Delaware, New York, and New Jersey comprised the Middle Colonies. The governments of these colonies were usually proprietary. This means that after receiving a land grant from the king, a company or person selected an official or administrator to govern the colony. The economies of the Middle Colonies were a diverse mixture of agriculture, shipbuilding, and logging. This rich economic base and tolerant societies of colonies like Pennsylvania attracted migrants from surrounding regions and immigrants from Europe like the Scots-Irish. |

| Southern Colonies | North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia made up the Southern colonies. The economies of the South depended on cash crops like rice and indigo. Unlike the Chesapeake, the South did not use indentured servants for labor; they depended solely on the use of African slaves. All colonial governments in the South elected their own legislatures but were royal colonies governed directly by the crown’s governor. |

Conflict with Native Americans

All thirteen British colonies encountered conflict with Native Americans at some point, often as a result of encroaching and expanding onto Native lands. The settlement of Jamestown in the middle of the Powhatan Confederacy led to the First and Second Powhatan Wars, ending in 1646 with a treaty that removed the Powhatans from much of their original lands. In 1676, Bacon’s Rebellion began due to conflicts with former indentured servants and Native Americans on the western borders of Virginian society.

The Puritan-Pequot War (1637-1638) that led to the massacre of roughly 500 Pequot men, women, and children led the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony to believe that their success was a sign of God’s favor. This led to further expansion and, ultimately, Metacom’s War (1675-1678), which ended with massive casualties for both sides. But violence wasn’t even always necessary. In Pennsylvania, the Walking Purchase of 1737 swindled the Delaware tribe out of roughly 1,200 acres of land at the hands of William Penn’s son.

Ultimately, the men and women who migrated to the thirteen British colonies did so for a variety of economic, social, and religious reasons. The settlements they created varied in structure but held the commonality that they were working within a mercantilist economy. They also all had conflicts with Native Americans over land and cultural differences, which impacted decisions and policies for expansion for decades.

**Quick Tip: Native American history surrounds local schools across the United States. Students should work with their teachers and local historical societies to learn more about these local tribes, and how migration and settlement patterns affected their sustainability and development.

Period 3 (1754-1800)

After the French and Indian War, the British claimed land in the Americas extending West of the Appalachian Mountains. Native tribes like the Iroquois, who sided with the British during the war, largely rejected these claims. Nevertheless, mixtures of violence and bribes led to decreased tribal lands.

Post French and Indian War

In 1763, Pontiac’s Rebellion in the Ohio River Valley led the British government to institute Proclamation of 1763, which forbid westward expansion West of the Appalachian Mountains. Colonists who saw access to property as fundamental freedom decried the proclamation as an infringement of their rights as Englishmen. Others, like the Scots-Irish Paxton Boys, exacted their revenge against Native Americans when they felt that colonial governments did not do enough to protect them.

Some settlers also felt a sense of deepening economic and social division associated with westward migration. In the mid-eighteenth century, a group of North Carolina vigilante rebels called the Regulators fought against corruption in their colonial government. The Regulators argued that despite living on less valuable “frontier” land, officials taxed them at the same levels as those living on fertile coastal land. They also complained that despite paying these excessive taxes, the government did little to protect them.

Following the American Revolution, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 created a Northwest Territory and provided a means of admitting new states to the Union from that territory. Like the decades before, this government declaration stood in contrast with Native American claims to the same land. In 1794, the Battle of Fallen Timbers and subsequent Treaty of Greenville (1795) secured the hotly-contested Ohio River Valley for the United States. In the treaty, the United States acknowledged Native American ownership of Ohio, and therefore paid them for it; in exchange, Native Americans accepted American sovereignty.

Despite the end of the American Revolution with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, British soldiers remained in the American West during the late eighteenth century. These soldiers repeatedly worked with Native American tribes against the new United States government, including providing weapons for attacks. Despite stipulations in Jay’s Treaty (1794) that this collusion end, tensions between the United States and Britain continued to increase, ultimately leading to war.

Period 4 (1800-1848)

Immigration

College Board does not explicitly attach the theme of migration and settlement to this period in the curriculum framework. Still, the Market Revolution does include one major immigrant movement that is important to know.

From roughly the 1820s to the 1840s, Irish and German immigrants made their way to the United States as part of “Old” immigration. This is often juxtaposed with “New” immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans in the Gilded Age (1865-1898).

For Irish immigrants, the biggest push factor was the Irish potato famine, in which roughly one million people died of starvation. German immigrants came in search of religious and political freedom.

For both groups, the pull factor was economic opportunity. Irish immigrants worked as both farmers and industrial workers in cities like New York and Chicago. German immigrants usually settled in farming areas of the North and Midwest, like Pennsylvania.

**Quick Tip: One of the most important things to understand when it comes to migration and settlement is the push and pull factors that lead people to move from one place to another. Learning the common push and pull factors across time can help make the types of connections necessary for getting the second “analysis and reasoning” point on the DBQ and LEQ. A Short Answer Question could also ask you to provide a push/pull factor during one period in part “a” and a similar push/pull factor in another period in part “b” (for example).

Period 5 (1844-1877)

While Period 5 addresses Manifest Destiny from the political perspective of increased sectionalism, the exam does not address this theme concerning migration and settlement until Period 6.

Period 6 (1865-1898)

Movements in migration and settlement during this period center around two main trends: westward migration following the Civil War and the growth of urbanization.

Westward Migration + Technology

The causes of westward migration following the Civil War were due largely to improved technology in farming and transportation. Some of these improvements, like the steel plow and mechanical reaper, originated in the early nineteenth century and continued to increase agricultural production. Other inventions, like barbed wire, revolutionized the way farmers separated and protected property.

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad was critical to the settlement of the West after the Civil War. The railroad not only bridged existing systems of the east with the Pacific coast but opened new markets in the West along the tracks’ route. As additional expansions to the original line unfolded, manufacturers in the east could count on farmers in the West to purchase their goods and vice versa.

Transportation was not the only new technology to revolutionize markets. The installation of the transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866 made it possible to communicate in a matter of seconds information that formerly took weeks to carry in ships across the Atlantic. Farmers and businessmen could receive updated values for goods and currency in real-time, making the practice of doing business more efficient.

Farmers

With increased efficiency in agriculture and business came problems for farmers. As farming prices became more efficient, food prices decreased. At the same time, ruthless business practices and government favor in the railroad industry led to the consolidation of that market in the face of increasing agricultural dependence on rail lines.

In the face of these problems, farmers created regional cooperative organizations like the Grange and the Colored Farmers’ Alliance. The primary function of groups like these was to collectively fight against the monopolistic powers of the railroad and grain elevator industries. In 1877, they had some success in the case of Munn v. Illinois, which ruled that state governments can regulate private businesses that serve public interests.

New modes of transportation moved thousands of migrants to the American West in the years between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the century. This movement was bolstered by innovations to help migrants become successful and community organizations that lent a voice to their growing concerns. The biggest effect of this migration, however, was not groundbreaking or inventive.

Land Disputes with Native Americans

Massive westward movement into the Great Plains after the Homestead Act (1862) led to disputes over land claimed by the Plains Indians - tribes like the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Osage. White settlers attempted to rid the Great Plains of Native Americans by killing their food source, the American bison, almost to extinction. When that did not work, the United States government resorted to violence.

When it comes to the AP exam, there are several terms involving the United States government and Union Army that are helpful to know as examples for this period.

| Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851) | This treaty set defined boundaries for Native American territory in the Great Plains. In exchange for allowing settlers and railroad workers to travel safely through tribal lands, the United States government was supposed to deliver resources to tribes. |

| Sand Creek Massacre (1864) | The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes were granted land by the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851), but gold-seekers and settlers violated that land. After making a new arrangement with the government, Black Kettle moved his band of Cheyenne to Sand Creek to hunt. U.S. Cavalry troops led an attack on them, killing 148 Native Americans - over half of them women and children. |

| Fetterman Massacre (1866) | In response to the Sand Creek Massacre, Native Americans across the Great Plains began attacking white settlers. The United States government began building forts along trails in the Black Hills, Sioux territory, to protect settlers. In 1866, Red Cloud and Crazy Horse led an attack against Captain William Fetterman and his men at Fort Phil Kearney, successfully defeating them. It was a clear victory for the Native Americans but led to treaties with smaller reservations and less government support. |

| Indian Appropriation Act (1871) | This law ended the ability of Native American tribes to make treaties with the United States government. |

| Battle of Little Bighorn (1876) | When white settlers discovered gold in the Black Hills, the United States government forced the Lakota Sioux to move from their ancestral lands. Some of the tribes missed the deadline for moving, so the federal government dispatched Lieutenant Colonel George Custer and the 7th Cavalry to confront them. Custer and his men were quickly overwhelmed by Sitting Bull and his men, and were defeated in what is often called “Custer’s Last Stand.” |

| Wounded Knee Massacre (1890) | After the killing of Sitting Bull and other followers of the Ghost Dance movement, the 7th Cavalry went to disarm a band of Sioux at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. In their attempt, a shot went off, and chaos ensued. The 7th Cavalry opened fire on the Sioux and massacred more than 200 men, women, and children. |

As violent action against Native Americans continued to unfold, the United States government increasingly promoted assimilationist policies. In 1881, poet and novelist Helen Hunt Jackson wrote A Century of Dishonor, in which she laid out the federal government’s atrocities against Native tribes over the previous hundred years. Despite some criticism, Congress appointed a special commission to look into her claims, ultimately leading to the Dawes Act of 1887.

The Dawes Act (or Dawes Severalty Act) allowed the federal government to divide reservation lands into individual plots of 160 acres for heads of family, or less for individuals. Those who accepted the land were granted United States citizenship, but could not legally own the land until after 25 years.

In addition to the Dawes Act, boarding schools like the Carlisle Indian School sought to assimilate Native American children into American culture by teaching them how to speak, dress, eat, and pray like white people. Such schools were notorious for their tactics of physically abusing children for speaking their native tongue, separating siblings from each other in gender-segregated environments, and forcing children to work long hours when not in class.

Both the Dawes Act and schools like Carlisle Indian School hoped to assimilate Native Americans into white culture by eliminating critical aspects of tribal identity - communal living and farming, native languages, gender equity in work, and religious traditions. For some tribes, the combination of violent warfare, starvation, and assimilation of their youngest generation did wipe out entire histories stretching thousands of years. Others, however, managed to hold on to tribal identities despite assimilationist policies and attempted to develop self-sustaining economic practices.

Population Boom

As farmers, ranchers, and miners moved West after the Civil War, a similar population boom occurred in urban centers east of the Mississippi River. At the start of the Civil War, the population of New York City was just over one million people. By 1880, that number had almost doubled due to immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.

In this period, Southern and Eastern Europeans left their homes (push factors) due to limited social mobility and poverty, as well as religious persecution. They came to the United States (pull factors) for industrial jobs. It is important to know that the pull factor for almost all immigrants to the United States is jobs. Knowing what kinds of jobs immigrants are working and where during each period will make it easy to plug that information in when necessary.

Ethnic Enclaves

Upon arriving in the United States, immigrants tended to settle into ethnic communities like “Chinatown” and “Little Italy.” This was practical, in a sense, because the new surroundings drew people to familiarity - those who spoke the same language, attended the same churches, and shopped in the same markets. However, the ethnic communities also existed because white Americans economically and socially prevented immigrants from moving into their parts of the city.

Immigrants

Immigrants often lived in buildings called tenements. These multi-story dwellings held concentrated numbers of people and often faced issues with sanitation and safety. Upper-class white individuals had little sympathy for the problems faced by those in the poorer parts of the city. Subscribing to a theory later called Social Darwinism, wealthy Americans saw inequality as an inevitable outcome of capitalism. Accordingly, those who lived in poverty did so because they were somehow inherently inferior.

In line with this logic, white Americans promoted the same agenda of assimilationist policies to immigrants as they did to Native Americans. Whites expected immigrants to abandon their home language in favor of English and adopt American food and dress. Social advocates like Jane Addams in Chicago set up settlement houses with the ultimate goal of helping immigrant women and children with the transition to American language and customs.

Just as the immigrant groups before them, Gilded Age immigrants made compromises in what they adopted and abandoned. Food was particularly permeable into American culture. For example, hamburgers, bratwursts (and other sausages), and sauerkraut all made their way into dominant culture as popular foods that were once exclusively found in German communities.

Westward expansion and urbanization both led to population growth in the years following the American Civil War. In both instances, the groups most affected by this growth - Native Americans and immigrants - faced challenges to their identities and stereotypes of inferiority. Meanwhile, white Americans capitalized on their wealth and influence to further their own political, social, and economic goals.

Period 7 (1890-1945)

Period 7 is one of the most extensive (in terms of events covered) in the timeline. It covers the Spanish American War, World War I, the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, the New Deal, and World War II. Migration and settlement during the period center on the movement of people during and as a result of wars.

The Rise of Communism

In 1917, the outbreak of the Bolshevik Revolution and subsequent United States involvement in World War I significantly changed the way Americans and the federal government treated immigrants. While the United States had always practiced nativism, a preference for native-born citizens and dislike of immigrants, anxiety over the spread of Communism led to widespread attacks on immigrant culture during World War I.

This widespread fear, called the Red Scare, led to restrictions on the First Amendment and attacks on labor activism. The case Schenck v. United States (1919) upheld the Espionage Act (1917), which made it a crime to undermine the United States or the armed forces during a war or aid the nation’s enemies. The federal government put its support behind “open shop” businesses, which did not require workers to join labor unions as conditions of employment.

The federal government also took steps to cut back immigration through new immigration laws. This began with the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which barred all immigration from China and was the nation’s first national immigration policy. In the 1920s, the United States adopted a quota system to handle immigrants from European nations. The government would determine the number of immigrants allowed into the United States from a European country as two percent of the number of people from that country living in the United States as of the 1890 census.

Migration in the US

Despite this cutback on immigration, urban centers continued to serve as a center of economic opportunity for millions of individuals. During World War I and World War II, many African Americans migrated from the rural South to the North and West (during World War II) to fill critical industrial jobs in the Great Migration.

African Americans leaving the Jim Crow South did so to escape violence, segregation, and limited economic opportunity. While cities in the North and West offered a reprieve from some of these issues, they were not without fault. In what is now called the Red Summer of 1919, black and white communities clashed in a series of violent race riots across the nation.

Urban areas also provided opportunities for women to escape their traditional economic roles. Women in the city worked as telephone operators, in department stores, and as secretaries. During both World War I and World War II, women readily filled vacant industrial jobs - a compelling cause for the 19th Amendment (1920). City life also gave women a new sense of independence and agency over their bodies, occupations, and futures.

Migration and settlement causes and effects during and after times of war vary dramatically depending on which side of the war a group is on. For those considered to be on the “good” side, the increased economic production associated with World War I and World War II led to tangible benefits. For those on the “bad” side, the stigma of negativity permeated all aspects of political, economic, and social life.

Period 8 (1945-1980)

Following World War II, the Servicemen's Readjustment Act (1944) - also known as the G.I. Bill - provided college tuition, low-interest home loans, and medical treatment for returning soldiers. Additionally, new medical technology, like penicillin and the polio vaccine, as well as innovations in child-rearing and development from perceived experts like Dr. Benjamin Spock, contributed to a baby boom.

To house their new families, white middle-class families moved to the suburbs. Dotted with prefabricated homes, these neighborhoods - often called Levittowns after real estate developer William Levitt - provided a clean and insulated environment for families to raise their children. Because mortgage agreements often forbid the sale or resale of homes to African Americans, the suburbs also guaranteed a type of segregation that the city could not.

A region of new development, spanning roughly from the Carolinas to California, was referred to as the Sun Belt for its generally warm climate and access to air conditioning. In contrast, the quickly dilapidated cities left behind by the exodus of white migrants became known as the Rust Belt. Formerly boisterous cities like Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and Detroit fell to ruins as large numbers of their tax base left for southern towns.

As people within the United States moved, immigrants from around the world sought new opportunities in the United States. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson passed a new immigration reform law that removed the quota systems in place since the 1920s. Holding a signing ceremony on Liberty Island under the Statue of Liberty, government officials hailed the new bill as a triumph of progress for American immigration policy. However, at the same time that the bill removed the old quota system, it set in place language limiting immigration from Central and South America.

Period 9 (1980-present)

During the Cold War, increasing population shifts to the Sun Belt and American West led to tremendous political and social influence in those regions. This trend is most noticeable in the election of “Sun Belt presidents” like Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan (elected at the start of this time period), George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George H.W. Bush.

Having presidents from the Sun Belt for the majority of this period has given that area a tremendous amount of power in the United States. The president’s agenda controls not only political aspects of American society, but social and economic issues as well - education reform, energy sources, and foreign policy.

As the United States crawled out of the economic recession that plagued much of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, the federal government took steps to ensure the safety of American jobs. The Immigration Reform and Control Act (1986) prohibited employers from hiring unauthorized immigrant workers for either temporary or permanent jobs. This reform bill most heavily impacted states in the South and West, which held the highest concentrations of immigrant populations from Central and Southern America and Asia.

Sample Questions

Sample SAQ✏️

| Rural and Urban Populations of the United States, 1860-1900 |

| Year |

| 1860 |

| 1870 |

| 1880 |

| 1890 |

| 1900 |

Source: United States Census Bureau.

Using your knowledge of United States History and the chart above, answer the following in complete sentences.

- Identify one specific cause of change for the rural population from 1860 to 1900.

- Identify one specific cause of change for the urban population from 1860 to 1900.

- Explain one way that a historical development in either the rural or urban region affected population change in the opposite region from 1860 to 1890.

Sample LEQ✏️

Evaluate the extent to which political and economic developments encouraged the settlement of the West from 1877 to 1898.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.