Browse By Unit

Unit 7 Overview: Torque and Rotational Motion

5 min read•june 18, 2024

Peter Apps

Kashvi Panjolia

Peter Apps

Kashvi Panjolia

Up until this point in the course, all of the motion covered has been described in terms of linear terms (forces, velocities, displacements, etc.) However a great deal of motion in the world isn’t about an object traveling anywhere, but instead rotating around a fixed axis (wheels, Merry-Go-Round, record/CD/DVD players).

Image courtesy of Giphy.

This unit looks at the concepts already covered in units 1-6 and applies them to a rotating object instead of an object moving in a straight line. These topics will account for ~10-16% of the AP exam questions and will take approximately 12-17 45 minute class periods to cover.

Applicable Big Ideas

- Big Idea #3: Force Interactions - The interactions of an object with other objects can be described by forces.

- Big Idea #4: Change - Interactions between systems can result in changes in those systems.

- Big Idea #5: Conservation - Changes that occur as a result of interactions are constrained by conservation laws.

Key Concepts

- Angular Displacement (𝜃)

- Angular Velocity (𝜔)

- Angular Acceleration (𝛼)

- Period (T)

- Torque (𝜏)

- Moment of Inertia (I)

- Rotational Kinetic Energy (Krot)

- Angular Momentum (L)

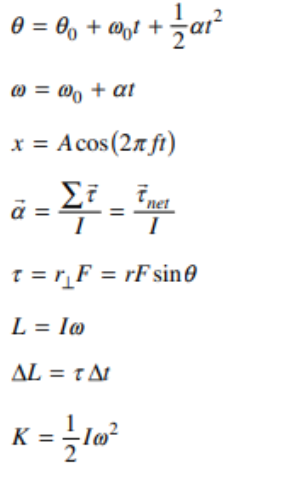

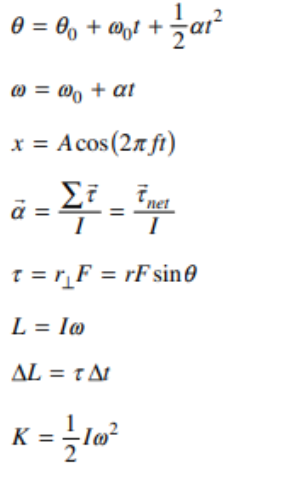

Key Equations

7.1 Rotational Kinematics

Rotational kinematics is the branch of physics that deals with the motion of rotating objects. In rotational kinematics, the rotational equivalent of linear motion quantities like displacement, velocity, and acceleration are used. These include angular displacement (Δθ), angular velocity (ω) and angular acceleration (α).

Angular displacement (Δθ) is the change in angular position of a rotating object, measured in radians. It is related to the linear displacement (s) of a point on the object by the equation Δθ = s/r, where r is the distance from the axis of rotation to the point.

Angular velocity (represented by the Greek lowercase omega ω) is the rate of change of angular displacement and is measured in radians per second. It is related to linear velocity (v) by the equation ω = v/r, where v is the linear velocity of a point on the object and r is the distance from the axis of rotation to the point.

Angular acceleration (represented by the Greek lowercase alpha α) is the rate of change of angular velocity and is measured in radians per second squared. It is related to linear acceleration (a) by the equation α = a/r, where a is the linear acceleration of a point on the object and r is the distance from the axis of rotation to the point.

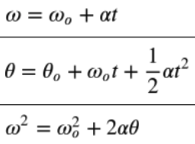

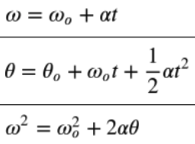

Rotational kinematics also involves the use of equations of motion for rotational motion. There are three rotational kinematics equations that are analogous to linear kinematics:

where ωf is the final angular velocity, ωi is the initial angular velocity, α is the angular acceleration, Δt is the time, and Δθ is the angular displacement.

It's important to note that angular displacement, velocity, and acceleration are all vector quantities, meaning they have both magnitude and direction. In physics, counterclockwise rotation is considered positive, while clockwise rotation is considered negative. This is not what you would expect, so make sure to practice identifying positive and negative directions so you can nail this concept. 🔄

7.2 Torque and Angular Acceleration

Torque (represented by the Greek lowercase 𝜏) is a measure of the twisting force that causes an object to rotate about an axis. It is a vector quantity and is defined as the product of the lever arm vector (r) and the portion of the force vector (F) that is perpendicular to the object. The unit of torque is Newton-meter (N·m) or Joule (J). Mathematically, torque can be represented as:

𝜏 = rFsinθ

where θ is the angle made by the lever arm vector (r) and the force vector (F) when the two vectors are placed tail-to-tail. ↖️↗️

The relationship between torque and angular acceleration can be represented by Newton's Second Law for rotation, which states that the net torque acting on an object is equal to the product of the object's moment of inertia (I) and its angular acceleration (α).

Σ𝜏 = Iα

The moment of inertia (I) is a measure of an object's resistance to rotational motion. It is measured in units of kilogram-meter squared (kgm^2). It depends on the object's mass and how far away that mass is from the axis of rotation. Inertia is a scalar quantity, while torque is a vector quantity. The moment of inertia of an object can be represented as: I = cMR^2

where M is the mass of the object, R is the radius of the object, and c is a constant determined by the shape you are working with.

This relationship allows us to calculate the angular acceleration of an object given the net torque acting on it and its moment of inertia.

7.3 Angular Momentum and Torque

Angular momentum (L) is a measure of an object's rotational motion. It is a vector quantity, meaning it has both magnitude and direction. Like linear momentum, angular momentum is conserved in systems where the net torque acting on an object is zero. The unit of angular momentum is kilogram-meter squared per second (kg·m²/s).

The angular momentum of an object can be calculated using the following equation:

L = Iω

where L is the angular momentum, I is the moment of inertia of the object and ω is the angular velocity of the object.

There are two more equations for angular momentum that can be used to analyze the angular motion of an object:

- The angular momentum equation for constant angular acceleration: ΔL = 𝜏Δt

This equation relates the change in angular momentum (ΔL) to the net torque (τ) acting on it over a period of time (Δt).

- The angular momentum equation relative to a fixed point for an object moving in a straight line: L=mvr

In this equation, m is the mass of the object, measured in kilograms (kg), v is the linear velocity of a point on the object, measured in meters per second (m/s), and r is the distance from the axis of rotation to the point on the object, measured in meters (m).

These equations can be used to analyze the angular motion of an object and to understand how torque, angular velocity, and angular momentum are related.

7.4 Conservation of Angular Momentum

Conservation of angular momentum states that the total angular momentum of a closed system (a system where no net external torque is acting on it) remains constant over time. This means that if the net torque acting on an object or system is zero, the angular momentum of the object or system will not change.

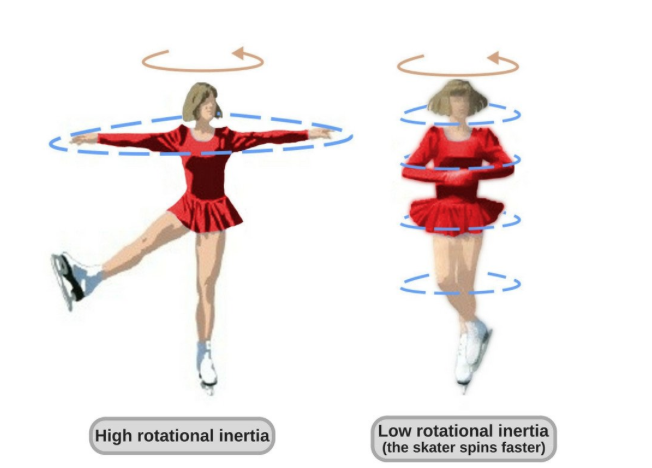

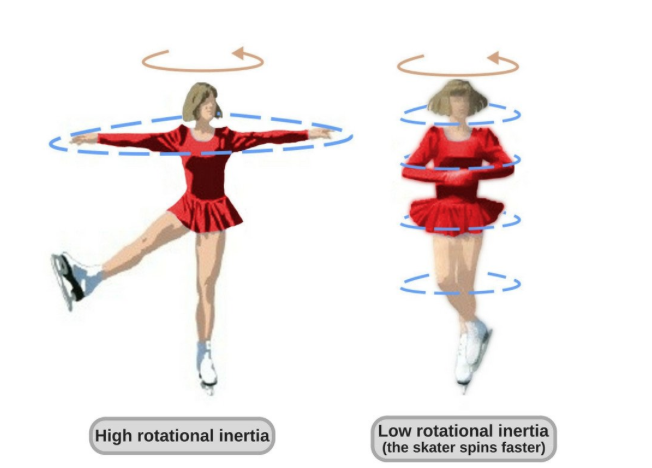

For example, if a figure skater is spinning with her arms extended and then brings her arms in close to her body, the angular momentum of her body will remain the same. The skater's moment of inertia will decrease as she brings her arms in closer to her body, but her angular velocity will increase by the same proportion to compensate and keep the angular momentum constant.

Image courtesy of ScienceABC.

🎥Watch: AP Physics 1 - Unit 7 Streams

<< Hide Menu

Unit 7 Overview: Torque and Rotational Motion

5 min read•june 18, 2024

Peter Apps

Kashvi Panjolia

Peter Apps

Kashvi Panjolia

Up until this point in the course, all of the motion covered has been described in terms of linear terms (forces, velocities, displacements, etc.) However a great deal of motion in the world isn’t about an object traveling anywhere, but instead rotating around a fixed axis (wheels, Merry-Go-Round, record/CD/DVD players).

Image courtesy of Giphy.

This unit looks at the concepts already covered in units 1-6 and applies them to a rotating object instead of an object moving in a straight line. These topics will account for ~10-16% of the AP exam questions and will take approximately 12-17 45 minute class periods to cover.

Applicable Big Ideas

- Big Idea #3: Force Interactions - The interactions of an object with other objects can be described by forces.

- Big Idea #4: Change - Interactions between systems can result in changes in those systems.

- Big Idea #5: Conservation - Changes that occur as a result of interactions are constrained by conservation laws.

Key Concepts

- Angular Displacement (𝜃)

- Angular Velocity (𝜔)

- Angular Acceleration (𝛼)

- Period (T)

- Torque (𝜏)

- Moment of Inertia (I)

- Rotational Kinetic Energy (Krot)

- Angular Momentum (L)

Key Equations

7.1 Rotational Kinematics

Rotational kinematics is the branch of physics that deals with the motion of rotating objects. In rotational kinematics, the rotational equivalent of linear motion quantities like displacement, velocity, and acceleration are used. These include angular displacement (Δθ), angular velocity (ω) and angular acceleration (α).

Angular displacement (Δθ) is the change in angular position of a rotating object, measured in radians. It is related to the linear displacement (s) of a point on the object by the equation Δθ = s/r, where r is the distance from the axis of rotation to the point.

Angular velocity (represented by the Greek lowercase omega ω) is the rate of change of angular displacement and is measured in radians per second. It is related to linear velocity (v) by the equation ω = v/r, where v is the linear velocity of a point on the object and r is the distance from the axis of rotation to the point.

Angular acceleration (represented by the Greek lowercase alpha α) is the rate of change of angular velocity and is measured in radians per second squared. It is related to linear acceleration (a) by the equation α = a/r, where a is the linear acceleration of a point on the object and r is the distance from the axis of rotation to the point.

Rotational kinematics also involves the use of equations of motion for rotational motion. There are three rotational kinematics equations that are analogous to linear kinematics:

where ωf is the final angular velocity, ωi is the initial angular velocity, α is the angular acceleration, Δt is the time, and Δθ is the angular displacement.

It's important to note that angular displacement, velocity, and acceleration are all vector quantities, meaning they have both magnitude and direction. In physics, counterclockwise rotation is considered positive, while clockwise rotation is considered negative. This is not what you would expect, so make sure to practice identifying positive and negative directions so you can nail this concept. 🔄

7.2 Torque and Angular Acceleration

Torque (represented by the Greek lowercase 𝜏) is a measure of the twisting force that causes an object to rotate about an axis. It is a vector quantity and is defined as the product of the lever arm vector (r) and the portion of the force vector (F) that is perpendicular to the object. The unit of torque is Newton-meter (N·m) or Joule (J). Mathematically, torque can be represented as:

𝜏 = rFsinθ

where θ is the angle made by the lever arm vector (r) and the force vector (F) when the two vectors are placed tail-to-tail. ↖️↗️

The relationship between torque and angular acceleration can be represented by Newton's Second Law for rotation, which states that the net torque acting on an object is equal to the product of the object's moment of inertia (I) and its angular acceleration (α).

Σ𝜏 = Iα

The moment of inertia (I) is a measure of an object's resistance to rotational motion. It is measured in units of kilogram-meter squared (kgm^2). It depends on the object's mass and how far away that mass is from the axis of rotation. Inertia is a scalar quantity, while torque is a vector quantity. The moment of inertia of an object can be represented as: I = cMR^2

where M is the mass of the object, R is the radius of the object, and c is a constant determined by the shape you are working with.

This relationship allows us to calculate the angular acceleration of an object given the net torque acting on it and its moment of inertia.

7.3 Angular Momentum and Torque

Angular momentum (L) is a measure of an object's rotational motion. It is a vector quantity, meaning it has both magnitude and direction. Like linear momentum, angular momentum is conserved in systems where the net torque acting on an object is zero. The unit of angular momentum is kilogram-meter squared per second (kg·m²/s).

The angular momentum of an object can be calculated using the following equation:

L = Iω

where L is the angular momentum, I is the moment of inertia of the object and ω is the angular velocity of the object.

There are two more equations for angular momentum that can be used to analyze the angular motion of an object:

- The angular momentum equation for constant angular acceleration: ΔL = 𝜏Δt

This equation relates the change in angular momentum (ΔL) to the net torque (τ) acting on it over a period of time (Δt).

- The angular momentum equation relative to a fixed point for an object moving in a straight line: L=mvr

In this equation, m is the mass of the object, measured in kilograms (kg), v is the linear velocity of a point on the object, measured in meters per second (m/s), and r is the distance from the axis of rotation to the point on the object, measured in meters (m).

These equations can be used to analyze the angular motion of an object and to understand how torque, angular velocity, and angular momentum are related.

7.4 Conservation of Angular Momentum

Conservation of angular momentum states that the total angular momentum of a closed system (a system where no net external torque is acting on it) remains constant over time. This means that if the net torque acting on an object or system is zero, the angular momentum of the object or system will not change.

For example, if a figure skater is spinning with her arms extended and then brings her arms in close to her body, the angular momentum of her body will remain the same. The skater's moment of inertia will decrease as she brings her arms in closer to her body, but her angular velocity will increase by the same proportion to compensate and keep the angular momentum constant.

Image courtesy of ScienceABC.

🎥Watch: AP Physics 1 - Unit 7 Streams

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.