Browse By Unit

6.5 Motive and Motivic Transformation

7 min read•june 18, 2024

Sumi Vora

Sumi Vora

Motives

How do we create structure within the melody of a musical piece? Just like in literature, a motive in music theory, also known as a motif, is a short musical phrase or idea that is used as the basis for a larger composition. A motive is typically made up of a few notes and is repeated or varied throughout a piece of music. It can be the main theme of the piece, a subsidiary theme, or a recurring element that is used to unify the different sections of a composition.

In music theory, a motive is considered a building block of a larger composition, serving as the foundation for the development of themes, harmonies, and rhythms. It is a way for a composer to create coherence and unity in a piece by using a small, recognizable idea as a starting point for more complex musical structures. Motives are usually characterized by pitch, contour, or rhythm, meaning that if any of these qualities of a short musical passage are repeated throughout a piece of music, we might consider it a motive.

Motives should be long enough to represent a thematic idea in the melody of a piece of music (very rarely will a motive just be one note), but they should be short enough that they are just a small musical idea. Usually, motives won’t be a full phrase – they may last a measure or two at most.

Here are a few examples of motives in classical music:

- Beethoven's Symphony No. 5: The opening four notes (short-short-short-long) is one of the most famous examples of a motive. This motive is used throughout the entire Symphony, and it serves as the foundation for the development of the themes, harmonies, and rhythms.

- Mozart's Symphony No. 40: The first movement of this Symphony features a motive that is made up of two rising notes, followed by two falling notes. This motive is used as the basis for the development of the main theme.

- Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5: The first movement of this Symphony features a motive that is made up of three rising notes, followed by a falling fourth note. This motive is used as the basis for the development of the main theme.

- Bach's "Brandenburg Concerto No. 3": The main theme of the first movement is a simple and recognizable motive, which is developed and expanded throughout the movement.

- Brahms's "Symphony No. 1": The main theme of the first movement is a simple and recognizable motive, which is developed and expanded throughout the movement.

- Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata" The first movement starts with a motive that is repeated several times throughout the movement. This motive is used as the foundation for the development of the main theme.

These are just a few examples of how motives can be used in classical music. Almost all pieces of classical music have motives.

Motivic Transformation

In order to add variety in the melody of a musical piece while still remaining cohesive and emphasizing musical ideas, motives are usually transformed and varied throughout a piece. There are a few common ways to transform motives:

- Transposed motives: when the motive appears on a different scale degree

- Inverted motives: reversing the direction of each diatonic interval in a motive

- Extended motives: repeating a portion of the motive to make it longer

- Truncated motives: cutting of the end of the motive to make it shorter

- Fragmented motives: taking a small but recognizable piece of music in the motive and repeating with with transpositions or other variations

Let’s dive into each of these in more detail:

Transposed Motives

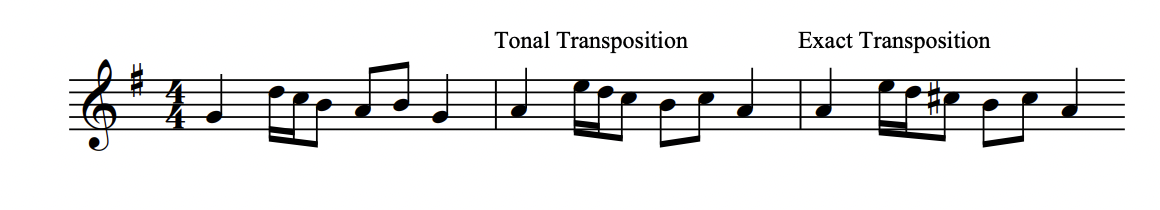

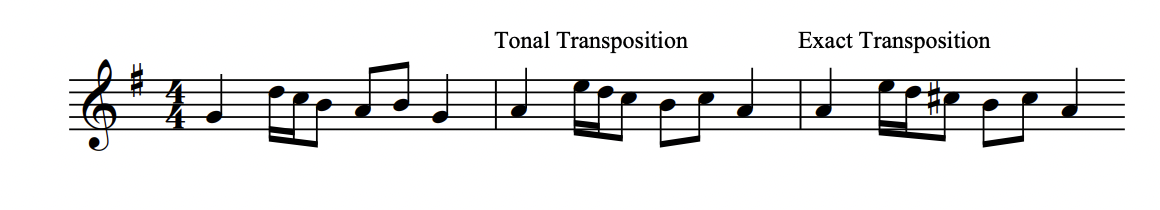

A transposed motive is a musical phrase or idea that has been moved to a different pitch level. This is achieved by changing the pitch of each note in the motive by a specific interval, such as a fifth or an octave. Transposing a motive can be used to create variation in a composition and to generate new melodic and harmonic possibilities.

For example, a motive that starts on C can be transposed to start on G, resulting in a different melody but still maintaining the same rhythm and intervals. Transposing a motive can also be used to modulate to a different key, which can create a sense of tension and release in a composition.

Transposed motives can be exact (or chromatic), meaning that the composer uses accidentals to make the quality of each interval in the transposed motive the same as the original motive, or they can be tonal, meaning that the composer stays within the diatonic scale when transposing the motive.

Here is an example:

Image via Gottry Percussion

Inverted Motives

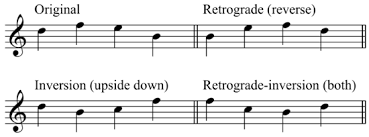

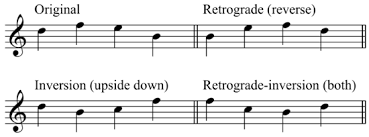

A motive inversion is a technique used in music composition where the intervals between the notes in a motive are reversed. This creates a new melody that is derived from the original motive, but with a different shape and character. For example, if a motive is made up of the intervals of a rising fifth and a falling third, its inversion would be a falling fifth and a rising third. This will create a new melody that is based on the original motive, but with a different character.

It's worth mentioning that there are different types of inversions, such as the inversion of melody, inversion of harmony, and inversion of rhythm, which can be used to create different effects in music. For example, if a motive is just defined by its contour, you might invert the contour of the motive, but not invert the exact intervals.

Retrograde is another technique related to inversion. Motive retrograde is a technique used in music composition where the notes of a motive are played in reverse order.

For example, if a motive is made up of the notes C, D, E, F, the retrograde of that motive would be F, E, D, C. This will create a new melody that is based on the original motive, but with a different character. Retrograding a motive can also be used in conjunction with other techniques such as inversion, transposition and augmentation to create new and interesting variations of the original motive.

Here are examples of motive inversion and retrograde. You can also have retrograde inversion, which is both retrograde and inversion at the same time!

Image via Steemit

Extended and Truncated Motives

An extended motive is a technique where the original motive is repeated, but with added notes or phrases that prolong the original idea. For example, a motive that is made up of four notes can be extended to eight notes by repeating it and adding new notes. You can also embellish motives by adding ornamentations or extra notes to make the melody more complex.

On the other hand, a truncated motive is a technique where the original motive is shortened by removing some of the notes. When truncating a motive, be careful to make sure that the thematic nature of the motive is still preserved – you shouldn’t shorten it too much!

Fragmented Motives

Fragmented motives are a technique used in music composition where the notes of a motive are broken up and separated, creating a sense of fragmentation or disjunction. This can be achieved by dividing the notes of the motive into smaller groups or by interrupting the continuity of the motive with rests or other melodic or rhythmic elements.

For example, a motive that is made up of four notes can be fragmented by separating the notes with rests, or by dividing the notes into groups of two notes each. This can create a sense of disjunction and dissonance and can be used to create a sense of tension and release in a composition.

What is the difference between fragmenting and extending motives? Primarily, fragmenting means breaking up a motive into different pieces and adding other melodic ideas or rhythmic elements in between these pieces. When extending a motive, you might add some ornamentation, but you are focused on repeating the whole motive, and maybe adding some melodic elements in between these repetitions.

🦜Polly wants a progress tracker: Listen to one of the pieces with famous motives in the examples above, or write your own short motive. Can you fragment it and develop it using other motivic transformation techniques to create a whole phrase? Bonus points if you can add a harmony to this melody!

Transforming Rhythmic Motives

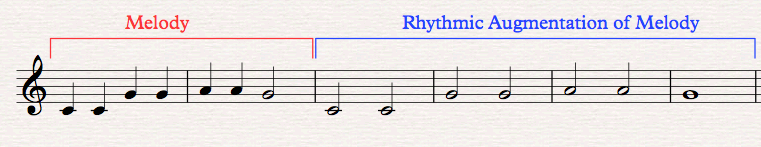

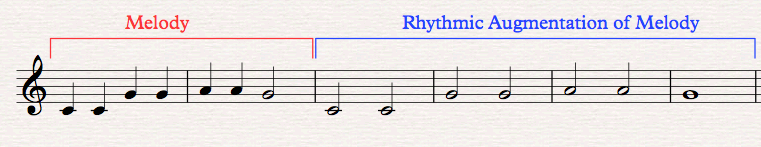

When transforming rhythmic motives, e.g. the short-short-short-long rhythmic motive in Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, there are two primary techniques: diminution and augmentation.

Motivic augmentation is the technique of lengthening the duration of the notes in a motive. This can be achieved by repeating the notes of the motive, or by adding notes to the motive. For example, a motive that is made up of four eighth notes can be augmented to four quarter notes.

Image via Music Theory Academy

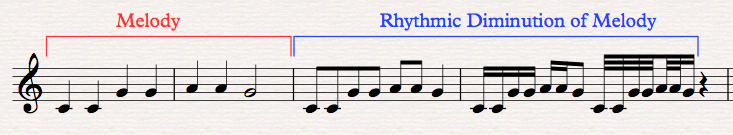

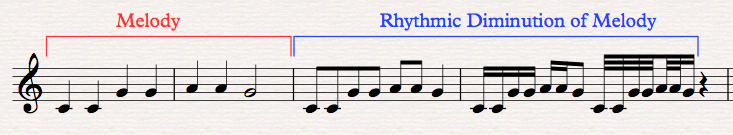

Similarly, motivic diminution is the technique of shortening the duration of the notes in a motive. This can be achieved by dividing the notes of the motive into smaller groups or by interrupting the continuity of the motive with rests or other melodic or rhythmic elements.

Image via Music Theory Academy

If a motive has both rhythmic or melodic elements, you can use augmentation and diminution with other motivic transformation techniques. Note that sometimes, augmentation and diminution can also refer to increasing or decreasing the size of intervals in a contour motive.

<< Hide Menu

6.5 Motive and Motivic Transformation

7 min read•june 18, 2024

Sumi Vora

Sumi Vora

Motives

How do we create structure within the melody of a musical piece? Just like in literature, a motive in music theory, also known as a motif, is a short musical phrase or idea that is used as the basis for a larger composition. A motive is typically made up of a few notes and is repeated or varied throughout a piece of music. It can be the main theme of the piece, a subsidiary theme, or a recurring element that is used to unify the different sections of a composition.

In music theory, a motive is considered a building block of a larger composition, serving as the foundation for the development of themes, harmonies, and rhythms. It is a way for a composer to create coherence and unity in a piece by using a small, recognizable idea as a starting point for more complex musical structures. Motives are usually characterized by pitch, contour, or rhythm, meaning that if any of these qualities of a short musical passage are repeated throughout a piece of music, we might consider it a motive.

Motives should be long enough to represent a thematic idea in the melody of a piece of music (very rarely will a motive just be one note), but they should be short enough that they are just a small musical idea. Usually, motives won’t be a full phrase – they may last a measure or two at most.

Here are a few examples of motives in classical music:

- Beethoven's Symphony No. 5: The opening four notes (short-short-short-long) is one of the most famous examples of a motive. This motive is used throughout the entire Symphony, and it serves as the foundation for the development of the themes, harmonies, and rhythms.

- Mozart's Symphony No. 40: The first movement of this Symphony features a motive that is made up of two rising notes, followed by two falling notes. This motive is used as the basis for the development of the main theme.

- Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5: The first movement of this Symphony features a motive that is made up of three rising notes, followed by a falling fourth note. This motive is used as the basis for the development of the main theme.

- Bach's "Brandenburg Concerto No. 3": The main theme of the first movement is a simple and recognizable motive, which is developed and expanded throughout the movement.

- Brahms's "Symphony No. 1": The main theme of the first movement is a simple and recognizable motive, which is developed and expanded throughout the movement.

- Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata" The first movement starts with a motive that is repeated several times throughout the movement. This motive is used as the foundation for the development of the main theme.

These are just a few examples of how motives can be used in classical music. Almost all pieces of classical music have motives.

Motivic Transformation

In order to add variety in the melody of a musical piece while still remaining cohesive and emphasizing musical ideas, motives are usually transformed and varied throughout a piece. There are a few common ways to transform motives:

- Transposed motives: when the motive appears on a different scale degree

- Inverted motives: reversing the direction of each diatonic interval in a motive

- Extended motives: repeating a portion of the motive to make it longer

- Truncated motives: cutting of the end of the motive to make it shorter

- Fragmented motives: taking a small but recognizable piece of music in the motive and repeating with with transpositions or other variations

Let’s dive into each of these in more detail:

Transposed Motives

A transposed motive is a musical phrase or idea that has been moved to a different pitch level. This is achieved by changing the pitch of each note in the motive by a specific interval, such as a fifth or an octave. Transposing a motive can be used to create variation in a composition and to generate new melodic and harmonic possibilities.

For example, a motive that starts on C can be transposed to start on G, resulting in a different melody but still maintaining the same rhythm and intervals. Transposing a motive can also be used to modulate to a different key, which can create a sense of tension and release in a composition.

Transposed motives can be exact (or chromatic), meaning that the composer uses accidentals to make the quality of each interval in the transposed motive the same as the original motive, or they can be tonal, meaning that the composer stays within the diatonic scale when transposing the motive.

Here is an example:

Image via Gottry Percussion

Inverted Motives

A motive inversion is a technique used in music composition where the intervals between the notes in a motive are reversed. This creates a new melody that is derived from the original motive, but with a different shape and character. For example, if a motive is made up of the intervals of a rising fifth and a falling third, its inversion would be a falling fifth and a rising third. This will create a new melody that is based on the original motive, but with a different character.

It's worth mentioning that there are different types of inversions, such as the inversion of melody, inversion of harmony, and inversion of rhythm, which can be used to create different effects in music. For example, if a motive is just defined by its contour, you might invert the contour of the motive, but not invert the exact intervals.

Retrograde is another technique related to inversion. Motive retrograde is a technique used in music composition where the notes of a motive are played in reverse order.

For example, if a motive is made up of the notes C, D, E, F, the retrograde of that motive would be F, E, D, C. This will create a new melody that is based on the original motive, but with a different character. Retrograding a motive can also be used in conjunction with other techniques such as inversion, transposition and augmentation to create new and interesting variations of the original motive.

Here are examples of motive inversion and retrograde. You can also have retrograde inversion, which is both retrograde and inversion at the same time!

Image via Steemit

Extended and Truncated Motives

An extended motive is a technique where the original motive is repeated, but with added notes or phrases that prolong the original idea. For example, a motive that is made up of four notes can be extended to eight notes by repeating it and adding new notes. You can also embellish motives by adding ornamentations or extra notes to make the melody more complex.

On the other hand, a truncated motive is a technique where the original motive is shortened by removing some of the notes. When truncating a motive, be careful to make sure that the thematic nature of the motive is still preserved – you shouldn’t shorten it too much!

Fragmented Motives

Fragmented motives are a technique used in music composition where the notes of a motive are broken up and separated, creating a sense of fragmentation or disjunction. This can be achieved by dividing the notes of the motive into smaller groups or by interrupting the continuity of the motive with rests or other melodic or rhythmic elements.

For example, a motive that is made up of four notes can be fragmented by separating the notes with rests, or by dividing the notes into groups of two notes each. This can create a sense of disjunction and dissonance and can be used to create a sense of tension and release in a composition.

What is the difference between fragmenting and extending motives? Primarily, fragmenting means breaking up a motive into different pieces and adding other melodic ideas or rhythmic elements in between these pieces. When extending a motive, you might add some ornamentation, but you are focused on repeating the whole motive, and maybe adding some melodic elements in between these repetitions.

🦜Polly wants a progress tracker: Listen to one of the pieces with famous motives in the examples above, or write your own short motive. Can you fragment it and develop it using other motivic transformation techniques to create a whole phrase? Bonus points if you can add a harmony to this melody!

Transforming Rhythmic Motives

When transforming rhythmic motives, e.g. the short-short-short-long rhythmic motive in Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, there are two primary techniques: diminution and augmentation.

Motivic augmentation is the technique of lengthening the duration of the notes in a motive. This can be achieved by repeating the notes of the motive, or by adding notes to the motive. For example, a motive that is made up of four eighth notes can be augmented to four quarter notes.

Image via Music Theory Academy

Similarly, motivic diminution is the technique of shortening the duration of the notes in a motive. This can be achieved by dividing the notes of the motive into smaller groups or by interrupting the continuity of the motive with rests or other melodic or rhythmic elements.

Image via Music Theory Academy

If a motive has both rhythmic or melodic elements, you can use augmentation and diminution with other motivic transformation techniques. Note that sometimes, augmentation and diminution can also refer to increasing or decreasing the size of intervals in a contour motive.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.