Browse By Unit

Cesar Torruella

Cesar Torruella

6/4 Chord Function

So far, you have learned different ways you can expand the predominant function, both in major and minor keys, and you have realized that other chords like iii or VI may lose their function and work in a different way. For example, IV can serve as a predominant but also as an extension of the tonic.

Similarly, in music, we don’t usually see 6/4 chords functioning in the same way as normal triads. If you have a keyboard or piano near you, try playing a I chord in C Major. Now, invert the chord so that you’re still playing a I chord, but it is in second inversion, i.e. a I 6/4 chord. You will probably notice that the tonic quality of the C Major chord is far less prominent.

Similarly, a V 6/4 chord doesn’t really sound like a dominant chord, and a IV 6/4 chord doesn’t really sound like a subdominant chord. That doesn’t mean that we don’t use 6/4 chords at all, though. There are 4 main contexts in which we do use 6/4 chords in music: cadential 6/4 chords, neighboring or pedal 6/4 chords, passing 6/4 chords, and arpeggiated 6/4 chords.

Here is a brief overview of what all of these 6/4 chords do:

- Cadential 6/4 chords are used to embellish dominant chords before a cadence. Usually, we have a I 6/4-V-I progression, where the upper notes in the I 6/4 chord move down stepwise. For example, in C Major, a I 6/4 chord with notes G-C-E will have the upper notes move down so we have a G-B-D root position V chord.

- Neighboring or pedal 6/4 chords are 6/4 chords that are used to embellish the top lines of a piece of music. Imagine a I-IV 6/4-I chord in C Major. The note in the bass line, C, stays the same, while the upper notes briefly change before going back to where they started.

- Passing 6/4 chords are chords where the bass line is moving up or down, usually by a third, and we fill in this skip with a 6/4 chord to fill in the bass. For example, if we have a I-V 6/4-I6 progression in C Major, then the bass line will be moving up stepwise as C-D-E, and the upper notes will move according to our voice leading rules.

- Arpeggiating 6/4 chords are used to embellish the same triad. So, we might have a I-I6-I 6/4 chord progression, where the bass note is changing. In this case, the 6/4 chord does have the same chord function as it would in the other inversions, but it is used to embellish the preceding triads rather than to add harmonic value in some way.

The main takeaway is that for all of these 6/4 chords, we are embellishing the existing harmonic structure of the piece – we are not adding any more harmonies.

Cadential 6/4 Chords

In this section, we are going to dive a little deeper into cadential 6/4 chords.

The cadential 6/4 chord is a I 6/4 chord that precedes a root position dominant triad, usually at a cadence. Although the cadential 6/4 contains the notes of the tonic triad, it does not exercise a tonic function but serves as a brief expansion of the dominant area. For this reason, we usually say that the cadential 6/4 has a dominant function, and rather than writing I 6/4-V, we will usually notate this pattern as V 6–5/4–3 to indicate that the 6/4 chord is “part of” the V chord.

Usually, the cadential 6/4 chord is written in a metrically stronger position than the dominant chord that follows it, and the upper voices of the 6/4 chord will move downward by step to reach the dominant chord. For example, if we have a cadential 6/4 chord in A Major, then the 6/4 chord will have the notes E-A-C, and then A and the C in the upper voices will move down to G and B respectively to spell the root position dominant chord E-G-B. Then, we will use our traditional voice leading rules to resolve the dominant chord to the I chord. The I chord will usually be written on a strong beat.

When we write cadential 6/4 chords, it is good practice to double the bass of the chord (not the root, like in traditional voice leading). This means that the fifth scale degree will show up twice in the 6/4 chord, which will emphasize its dominant function.

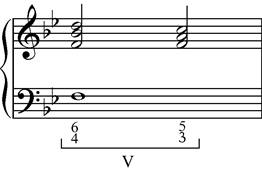

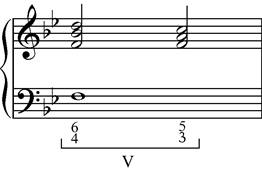

Here is an example of a cadential 6/4 chord. Although we will usually use the notation V 6–5/4–3 notation to write a cadential 6/4 chord, here is another acceptable way to notate the cadential 6/4.

Resolving to the Dominant Seventh

Can I write a cadential 6/4 chord to precede a V7-I cadence? Of course you can! When we follow a cadential 6/4 chord by a dominant triad, we usually retain the dominant voice that was doubled in the 6/4 chord in the dominant triad. In the example above in Bb Major, the 6/4 chord had notes F-F-B-D, and in the triad, we had notes F-F-A-C (notice that the bass note in the 6/4 chord is a whole note, meaning that it is also heard in the dominant triad. That means that in the V chord, we retained both of the Fs as common tones, and the A and the C moved down stepwise.

If we want to go from a I 6/4 to a V7 chord, all we would have to do is move one of those Fs down. Since a third inversion V7 chord usually doesn’t have a strong dominant sound, whichever F is in an upper voice would move down stepwise to an E, spelling F-E-A-C, a root position V7 chord.

To notate this in music, you will write this chord progression as V 8–7/6–5/4–3 in order to indicate that the 8th above the bass moves down to the 7th above the bass, the 6th moves down to the 5th, and the 4th moves down to the 3rd. Note that just like in regular figured bass notation, it doesn’t matter what order the notes in the chord are really in. Even if the 8th of the chord was in the alto voice and the 3rd of the chord was in the soprano voice, you would still write the figured bass notation as V 8–7/6–5/4–3.

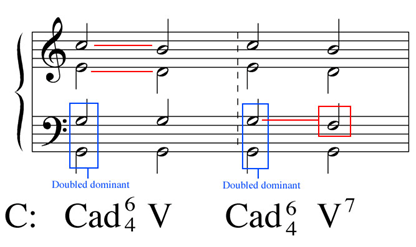

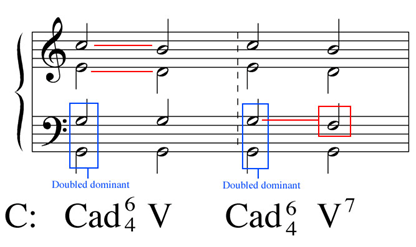

Here is an example of a cadential 6/4 chord moving to a V7 chord in a chord progression:

Voice Leading with the Cadential 6/4 Chords

First, remember to always double the bass of the cadential 6/4 chord. This reinforces the dominant function of the cadential 6/4 chord so that the 6/4 chord sounds like an embellishment to the dominant rather than a second inversion tonic triad. This also makes it easier to retain the common tone when moving to a dominant triad or move the doubled tone down stepwise to spell a dominant seventh chord.

Doubling the bass isn’t just a stylistic choice when writing cadential 6/4 chords. If you don’t double the bass, then the cadential 6/4 chord would be considered wrong in the AP Music Theory exam.

Second, it is a good idea to approach the cadential 6/4 chord with a predominant harmony, like a IV chord or a ii6 chord. This is usually just common practice when it comes to writing chord progressions: predominant harmonies should precede dominant harmonies. However, especially when writing cadential 6/4 chords, you should always have a strong predominant section.

There are two reasons for this. First, the cadential 6/4 loses its dominant function when preceded directly by the tonic section of a phrase, since the cadential 6/4 has a tonic harmony. Second, since the subdominant chords “want” to resolve to dominant chords, writing the cadential 6/4 between the subdominant and dominant harmonies creates good harmonic tension as listeners have to wait for the subdominant to resolve.

Cadential 6/4 chords should always go on a strong beat. Otherwise, the embellishment sounds too weak, and it will lose its musical effectiveness.

A quick note: If you write a cadential 6/4 chord correctly, you shouldn’t run into this problem, but you should always check for direct fifths and octaves in cadential 6/4 chords, since all of the upper voices are moving down stepwise in parallel motion.

Here are a few final examples to sum this section up:

- In the first chord progression, we see a cadential 6/4 chord solving to V. Notice how common tones are kept, and the other voices move down to the nearest tones.

- In the second measure, we see a cadential 6/4 solving to a V⁷ chord. See how the bass is kept the same, and SAT voices (Soprano, Alto, Tenor voices) all move down by step in parallel motion in order to resolve to the V7.

<< Hide Menu

Cesar Torruella

Cesar Torruella

6/4 Chord Function

So far, you have learned different ways you can expand the predominant function, both in major and minor keys, and you have realized that other chords like iii or VI may lose their function and work in a different way. For example, IV can serve as a predominant but also as an extension of the tonic.

Similarly, in music, we don’t usually see 6/4 chords functioning in the same way as normal triads. If you have a keyboard or piano near you, try playing a I chord in C Major. Now, invert the chord so that you’re still playing a I chord, but it is in second inversion, i.e. a I 6/4 chord. You will probably notice that the tonic quality of the C Major chord is far less prominent.

Similarly, a V 6/4 chord doesn’t really sound like a dominant chord, and a IV 6/4 chord doesn’t really sound like a subdominant chord. That doesn’t mean that we don’t use 6/4 chords at all, though. There are 4 main contexts in which we do use 6/4 chords in music: cadential 6/4 chords, neighboring or pedal 6/4 chords, passing 6/4 chords, and arpeggiated 6/4 chords.

Here is a brief overview of what all of these 6/4 chords do:

- Cadential 6/4 chords are used to embellish dominant chords before a cadence. Usually, we have a I 6/4-V-I progression, where the upper notes in the I 6/4 chord move down stepwise. For example, in C Major, a I 6/4 chord with notes G-C-E will have the upper notes move down so we have a G-B-D root position V chord.

- Neighboring or pedal 6/4 chords are 6/4 chords that are used to embellish the top lines of a piece of music. Imagine a I-IV 6/4-I chord in C Major. The note in the bass line, C, stays the same, while the upper notes briefly change before going back to where they started.

- Passing 6/4 chords are chords where the bass line is moving up or down, usually by a third, and we fill in this skip with a 6/4 chord to fill in the bass. For example, if we have a I-V 6/4-I6 progression in C Major, then the bass line will be moving up stepwise as C-D-E, and the upper notes will move according to our voice leading rules.

- Arpeggiating 6/4 chords are used to embellish the same triad. So, we might have a I-I6-I 6/4 chord progression, where the bass note is changing. In this case, the 6/4 chord does have the same chord function as it would in the other inversions, but it is used to embellish the preceding triads rather than to add harmonic value in some way.

The main takeaway is that for all of these 6/4 chords, we are embellishing the existing harmonic structure of the piece – we are not adding any more harmonies.

Cadential 6/4 Chords

In this section, we are going to dive a little deeper into cadential 6/4 chords.

The cadential 6/4 chord is a I 6/4 chord that precedes a root position dominant triad, usually at a cadence. Although the cadential 6/4 contains the notes of the tonic triad, it does not exercise a tonic function but serves as a brief expansion of the dominant area. For this reason, we usually say that the cadential 6/4 has a dominant function, and rather than writing I 6/4-V, we will usually notate this pattern as V 6–5/4–3 to indicate that the 6/4 chord is “part of” the V chord.

Usually, the cadential 6/4 chord is written in a metrically stronger position than the dominant chord that follows it, and the upper voices of the 6/4 chord will move downward by step to reach the dominant chord. For example, if we have a cadential 6/4 chord in A Major, then the 6/4 chord will have the notes E-A-C, and then A and the C in the upper voices will move down to G and B respectively to spell the root position dominant chord E-G-B. Then, we will use our traditional voice leading rules to resolve the dominant chord to the I chord. The I chord will usually be written on a strong beat.

When we write cadential 6/4 chords, it is good practice to double the bass of the chord (not the root, like in traditional voice leading). This means that the fifth scale degree will show up twice in the 6/4 chord, which will emphasize its dominant function.

Here is an example of a cadential 6/4 chord. Although we will usually use the notation V 6–5/4–3 notation to write a cadential 6/4 chord, here is another acceptable way to notate the cadential 6/4.

Resolving to the Dominant Seventh

Can I write a cadential 6/4 chord to precede a V7-I cadence? Of course you can! When we follow a cadential 6/4 chord by a dominant triad, we usually retain the dominant voice that was doubled in the 6/4 chord in the dominant triad. In the example above in Bb Major, the 6/4 chord had notes F-F-B-D, and in the triad, we had notes F-F-A-C (notice that the bass note in the 6/4 chord is a whole note, meaning that it is also heard in the dominant triad. That means that in the V chord, we retained both of the Fs as common tones, and the A and the C moved down stepwise.

If we want to go from a I 6/4 to a V7 chord, all we would have to do is move one of those Fs down. Since a third inversion V7 chord usually doesn’t have a strong dominant sound, whichever F is in an upper voice would move down stepwise to an E, spelling F-E-A-C, a root position V7 chord.

To notate this in music, you will write this chord progression as V 8–7/6–5/4–3 in order to indicate that the 8th above the bass moves down to the 7th above the bass, the 6th moves down to the 5th, and the 4th moves down to the 3rd. Note that just like in regular figured bass notation, it doesn’t matter what order the notes in the chord are really in. Even if the 8th of the chord was in the alto voice and the 3rd of the chord was in the soprano voice, you would still write the figured bass notation as V 8–7/6–5/4–3.

Here is an example of a cadential 6/4 chord moving to a V7 chord in a chord progression:

Voice Leading with the Cadential 6/4 Chords

First, remember to always double the bass of the cadential 6/4 chord. This reinforces the dominant function of the cadential 6/4 chord so that the 6/4 chord sounds like an embellishment to the dominant rather than a second inversion tonic triad. This also makes it easier to retain the common tone when moving to a dominant triad or move the doubled tone down stepwise to spell a dominant seventh chord.

Doubling the bass isn’t just a stylistic choice when writing cadential 6/4 chords. If you don’t double the bass, then the cadential 6/4 chord would be considered wrong in the AP Music Theory exam.

Second, it is a good idea to approach the cadential 6/4 chord with a predominant harmony, like a IV chord or a ii6 chord. This is usually just common practice when it comes to writing chord progressions: predominant harmonies should precede dominant harmonies. However, especially when writing cadential 6/4 chords, you should always have a strong predominant section.

There are two reasons for this. First, the cadential 6/4 loses its dominant function when preceded directly by the tonic section of a phrase, since the cadential 6/4 has a tonic harmony. Second, since the subdominant chords “want” to resolve to dominant chords, writing the cadential 6/4 between the subdominant and dominant harmonies creates good harmonic tension as listeners have to wait for the subdominant to resolve.

Cadential 6/4 chords should always go on a strong beat. Otherwise, the embellishment sounds too weak, and it will lose its musical effectiveness.

A quick note: If you write a cadential 6/4 chord correctly, you shouldn’t run into this problem, but you should always check for direct fifths and octaves in cadential 6/4 chords, since all of the upper voices are moving down stepwise in parallel motion.

Here are a few final examples to sum this section up:

- In the first chord progression, we see a cadential 6/4 chord solving to V. Notice how common tones are kept, and the other voices move down to the nearest tones.

- In the second measure, we see a cadential 6/4 solving to a V⁷ chord. See how the bass is kept the same, and SAT voices (Soprano, Alto, Tenor voices) all move down by step in parallel motion in order to resolve to the V7.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.