Browse By Unit

5.5 Cadences and Predominant Function

7 min read•june 18, 2024

Cesar Torruella

Cesar Torruella

Cadences are like the period at the end of our sentence. It announces we have arrived at the end. A cadence is the harmonic conclusion of a phrase. Most of the time, cadences are used to create a sense of resolution or closure. However, it is also possible for cadences to avoid giving closure, or give only partial closure, as in a deceptive cadence or a half cadence.

There are several types of cadences that we can study. Each has its own function in a piece of music. Here is a list of all of the types of cadences:

- Perfect Authentic = PAC

- Imperfect Authentic = IAC

- Plagal Cadence = PC

- Deceptive Cadence = DC

- Half Cadence = HC

- Phrygian Half Cadence = PHC

Authentic Cadences

An authentic cadence consists of a dominant function chord (V or vii) moving to a tonic. It is called an authentic cadence because of the dominant-tonic progression that provides a sense of resolution and finality to a phrase. Perfect authentic cadences are the strongest type of cadence, meaning that they provide the strongest sense of resolution in a piece of music.

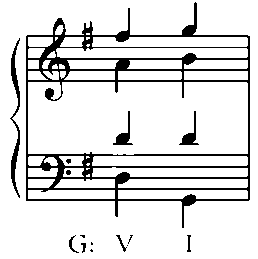

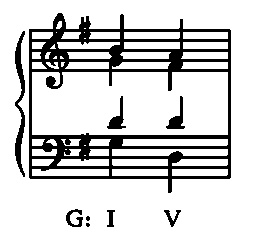

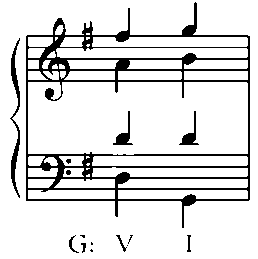

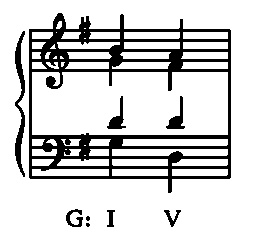

Usually, you will hear perfect authentic cadences at the end of a piece or at the end of sections of a piece. In order to be considered a perfect authentic cadence, a cadence must meet all the following criteria:Here is an example of a perfect authentic cadence. Notice how the leading tone must be in the soprano voice, since we want the soprano voice to end on the tonic. Of course, if the leading tone isn’t in the soprano voice, it is always possible to triple to tonic and omit the fifth of the tonic triad. However, it is preferable for a perfect authentic cadence to have all voices present.

- It must use a V chord as the dominant chord (as opposed to a vii or viio chord) ✅

- Both chords must be in root position. ✅

- The soprano voice must end on the tonic. ✅

- The soprano must move by step.✅

Here is an example of a perfect authentic cadence. Notice how the leading tone must be in the soprano voice, since we want the soprano voice to end on the tonic. Of course, if the leading tone isn’t in the soprano voice, it is always possible to triple to tonic and omit the fifth of the tonic triad. However, it is preferable for a perfect authentic cadence to have all voices present.

If the cadence doesn’t meet all those criteria, it’s considered to be an imperfect authentic cadence. Imperfect authentic cadences still provide a sense of resolution and finality to a phrase, but they are not as strong as perfect authentic cadences.

Imperfect authentic cadences are probably the most common type of cadence in music, and they are usually used to end phrases and sections of music. They might also be at the end of a musical piece. For example, a composer might use them at the end of a movement of a sonata before moving to the next movement.

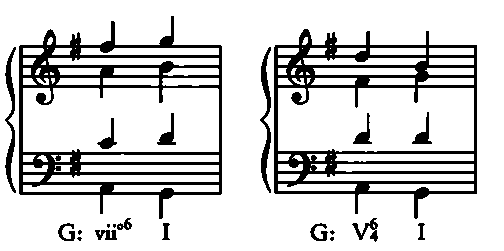

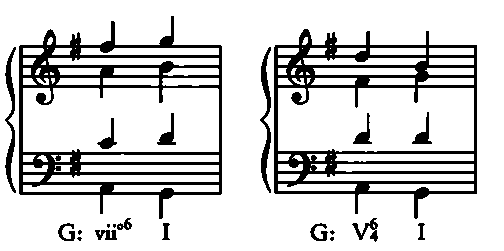

Here are two examples of imperfect authentic cadences. Notice how in the first example, the viio chord is in first inversion, meaning that the supertonic is in the bass line. It is common, when using vii chords, to resolve the supertonic down to the tonic, especially when the supertonic is in the bass line. It would be acceptable to have a vii6-I6 imperfect authentic cadence, but this cadence would be quite weak.

In the second example, there is a V 6/4 to I cadence. This is an extremely weak cadence – usually, 6/4 chords are not used at all in this context. However, since there is a dominant to tonic motion, there will still be some form of resolution. Since the dominant chord is very weak, it is smart to put the tonic chord in root position so that listeners can hear the cadence clearly.

In minor key, we can have V-i perfect and imperfect authentic cadences. However, we might have a V-I cadence as well. This is called a Picardy third. It originated in music during the Renaissance era, and it is most commonly used to end a piece of music in minor mode. You will almost never see a Picardy third in the middle of a piece of music.

Plagal Cadences

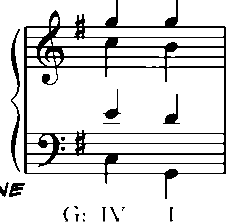

- A plagal cadence (PC) consists of a subdominant function chord (IV or ii) moving to tonic. If a ii chord is used in a plagal cadence, it is usually in first inversion (a ii6 chord) so that the fourth scale degree is in the base. Also, the third of the chord is usually doubled, so that we can have a stronger subdominant sound. It is called a plagal cadence because in Christian churches, the final “Amen” in hymns would have a IV-I progression. The ending of Handel’s Messiah uses a series of very powerful plagal cadences towards the end of the piece. This emphasizes the religious aspect of the piece.

However, plagal cadences are also used outside of religious music. The I-V-vi-IV chord progression is commonly used everywhere in music – especially in popular music. To see just how common this chord progression is, check out this funny video by the Axis of Awesome.

To be considered a Perfect Plagal Cadence, a cadence must meet all the following criteria:

- It must use a IV chord (not a ii) to lead into the tonic. Technically, you can use a IV7 chord to lead into the I chord, and it will still be a perfect plagal cadence. However, this is rare in music from the common practice period. ✅

- Both chords must be in root position. This is not required, but you should usually double the root in both chords as well. ✅

- The soprano must end on the tonic ✅

- The soprano must keep the common tone, meaning that the fifth of the IV chord (which is the tonic) should also be in the soprano line ✅

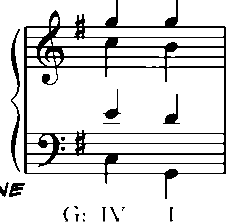

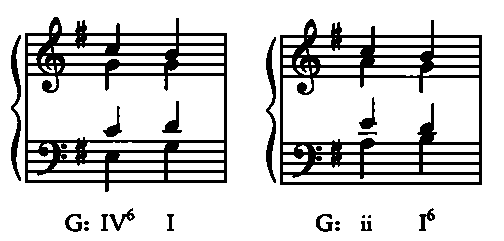

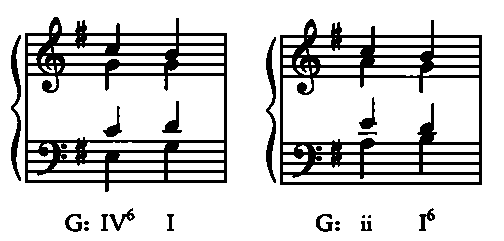

If the cadence doesn’t meet all those criteria, it’s considered to be an imperfect plagal cadence. Here are some examples of imperfect plagal cadences:

In the first example, notice that the root of the chord is still doubled in both instances, and we still keep the common tonic tone when leading into the I chord – this time, though, it is in the alto line. Keeping common tones whenever possible is just considered good voice leading practice, so it is good to do it regardless of whether you are trying to write a perfect cadence.

In the second example, we notice that the ii chord is in root position, which is a little bit rare when writing plagal cadences. The tonic chord is also in first inversion. As a result, this cadence will be much weaker than the cadence preceding it.

Half Cadences

Next, a half cadence is any cadence that ends on the dominant chord (V). Usually, in Major, we will go from a I chord to a V chord. Going from a IV chord to a V chord is also common, as the subdominant resolves to the dominant, giving some sense of resolution without going back to the “home” chord: the tonic.

When writing in minor mode, we can use a specific type of half cadence called the Phrygian half cadence, which must meet the following criteria:

- It occurs ONLY in minor key. ✅

- It uses a iv6 chord moving to V. The iv chord MUST be in first inversion ✅

- The soprano and bass move by step in contrary motion. Since the bass moves down by a half step, the soprano must therefore move up by a step. Usually, we achieve this by doubling the root and having it move up by step to the root of the V chord. ✅

- The soprano and bass both end on the dominant scale degree. ✅

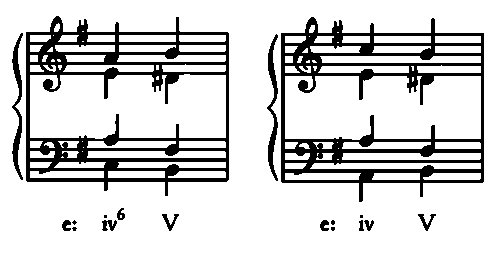

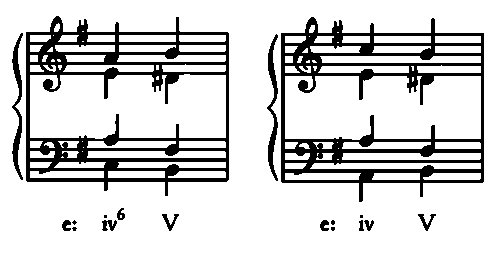

Here is an example of a Phrygian half cadence. Notice how the bass moves down by a half step – this is a good way to recognize phrygian cadences by ear. If you’ve been looking ahead, you might notice that this half step is a ii-I interval in Phrygian mode: hence the name Phrygian half cadence.

Note that a common mistake in writing phrygian cadences is the possibility to write an augmented second in a voice if you are not careful. If, for some reason, you have to double the third of the chord in the iv6 chord, then make sure that it does not lead into the third of the chord of the V chord – otherwise, you will get a dissonant augmented second in one of the voices.

Also, don’t forget to raise the leading tone in the V chord!

Phrygian half cadences were used quite frequently to end slow movements that move into faster movements, especially in Baroque music. They fell out of use in the Romantic and Modern periods, so using them gives a little bit of a “vintage” sound.

Deceptive Cadences

A deceptive cadence is a cadence where the dominant chord (V) resolves to something other than tonic, almost always the submediant chord (vi or VI). You’ll usually see this type of cadence inside of sections of music or inside of a piece – it is almost never used to end a piece of music.

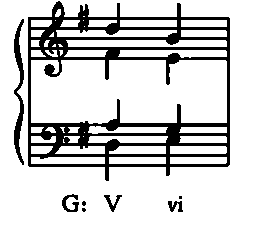

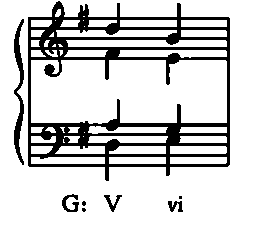

Here is an example of a deceptive cadence:

One thing to note is that there are “layers” of deceptive cadences. A V-vi deceptive cadence is much more common and less unsettling than a V-IV or V-iv deceptive cadence, for example.

<< Hide Menu

5.5 Cadences and Predominant Function

7 min read•june 18, 2024

Cesar Torruella

Cesar Torruella

Cadences are like the period at the end of our sentence. It announces we have arrived at the end. A cadence is the harmonic conclusion of a phrase. Most of the time, cadences are used to create a sense of resolution or closure. However, it is also possible for cadences to avoid giving closure, or give only partial closure, as in a deceptive cadence or a half cadence.

There are several types of cadences that we can study. Each has its own function in a piece of music. Here is a list of all of the types of cadences:

- Perfect Authentic = PAC

- Imperfect Authentic = IAC

- Plagal Cadence = PC

- Deceptive Cadence = DC

- Half Cadence = HC

- Phrygian Half Cadence = PHC

Authentic Cadences

An authentic cadence consists of a dominant function chord (V or vii) moving to a tonic. It is called an authentic cadence because of the dominant-tonic progression that provides a sense of resolution and finality to a phrase. Perfect authentic cadences are the strongest type of cadence, meaning that they provide the strongest sense of resolution in a piece of music.

Usually, you will hear perfect authentic cadences at the end of a piece or at the end of sections of a piece. In order to be considered a perfect authentic cadence, a cadence must meet all the following criteria:Here is an example of a perfect authentic cadence. Notice how the leading tone must be in the soprano voice, since we want the soprano voice to end on the tonic. Of course, if the leading tone isn’t in the soprano voice, it is always possible to triple to tonic and omit the fifth of the tonic triad. However, it is preferable for a perfect authentic cadence to have all voices present.

- It must use a V chord as the dominant chord (as opposed to a vii or viio chord) ✅

- Both chords must be in root position. ✅

- The soprano voice must end on the tonic. ✅

- The soprano must move by step.✅

Here is an example of a perfect authentic cadence. Notice how the leading tone must be in the soprano voice, since we want the soprano voice to end on the tonic. Of course, if the leading tone isn’t in the soprano voice, it is always possible to triple to tonic and omit the fifth of the tonic triad. However, it is preferable for a perfect authentic cadence to have all voices present.

If the cadence doesn’t meet all those criteria, it’s considered to be an imperfect authentic cadence. Imperfect authentic cadences still provide a sense of resolution and finality to a phrase, but they are not as strong as perfect authentic cadences.

Imperfect authentic cadences are probably the most common type of cadence in music, and they are usually used to end phrases and sections of music. They might also be at the end of a musical piece. For example, a composer might use them at the end of a movement of a sonata before moving to the next movement.

Here are two examples of imperfect authentic cadences. Notice how in the first example, the viio chord is in first inversion, meaning that the supertonic is in the bass line. It is common, when using vii chords, to resolve the supertonic down to the tonic, especially when the supertonic is in the bass line. It would be acceptable to have a vii6-I6 imperfect authentic cadence, but this cadence would be quite weak.

In the second example, there is a V 6/4 to I cadence. This is an extremely weak cadence – usually, 6/4 chords are not used at all in this context. However, since there is a dominant to tonic motion, there will still be some form of resolution. Since the dominant chord is very weak, it is smart to put the tonic chord in root position so that listeners can hear the cadence clearly.

In minor key, we can have V-i perfect and imperfect authentic cadences. However, we might have a V-I cadence as well. This is called a Picardy third. It originated in music during the Renaissance era, and it is most commonly used to end a piece of music in minor mode. You will almost never see a Picardy third in the middle of a piece of music.

Plagal Cadences

- A plagal cadence (PC) consists of a subdominant function chord (IV or ii) moving to tonic. If a ii chord is used in a plagal cadence, it is usually in first inversion (a ii6 chord) so that the fourth scale degree is in the base. Also, the third of the chord is usually doubled, so that we can have a stronger subdominant sound. It is called a plagal cadence because in Christian churches, the final “Amen” in hymns would have a IV-I progression. The ending of Handel’s Messiah uses a series of very powerful plagal cadences towards the end of the piece. This emphasizes the religious aspect of the piece.

However, plagal cadences are also used outside of religious music. The I-V-vi-IV chord progression is commonly used everywhere in music – especially in popular music. To see just how common this chord progression is, check out this funny video by the Axis of Awesome.

To be considered a Perfect Plagal Cadence, a cadence must meet all the following criteria:

- It must use a IV chord (not a ii) to lead into the tonic. Technically, you can use a IV7 chord to lead into the I chord, and it will still be a perfect plagal cadence. However, this is rare in music from the common practice period. ✅

- Both chords must be in root position. This is not required, but you should usually double the root in both chords as well. ✅

- The soprano must end on the tonic ✅

- The soprano must keep the common tone, meaning that the fifth of the IV chord (which is the tonic) should also be in the soprano line ✅

If the cadence doesn’t meet all those criteria, it’s considered to be an imperfect plagal cadence. Here are some examples of imperfect plagal cadences:

In the first example, notice that the root of the chord is still doubled in both instances, and we still keep the common tonic tone when leading into the I chord – this time, though, it is in the alto line. Keeping common tones whenever possible is just considered good voice leading practice, so it is good to do it regardless of whether you are trying to write a perfect cadence.

In the second example, we notice that the ii chord is in root position, which is a little bit rare when writing plagal cadences. The tonic chord is also in first inversion. As a result, this cadence will be much weaker than the cadence preceding it.

Half Cadences

Next, a half cadence is any cadence that ends on the dominant chord (V). Usually, in Major, we will go from a I chord to a V chord. Going from a IV chord to a V chord is also common, as the subdominant resolves to the dominant, giving some sense of resolution without going back to the “home” chord: the tonic.

When writing in minor mode, we can use a specific type of half cadence called the Phrygian half cadence, which must meet the following criteria:

- It occurs ONLY in minor key. ✅

- It uses a iv6 chord moving to V. The iv chord MUST be in first inversion ✅

- The soprano and bass move by step in contrary motion. Since the bass moves down by a half step, the soprano must therefore move up by a step. Usually, we achieve this by doubling the root and having it move up by step to the root of the V chord. ✅

- The soprano and bass both end on the dominant scale degree. ✅

Here is an example of a Phrygian half cadence. Notice how the bass moves down by a half step – this is a good way to recognize phrygian cadences by ear. If you’ve been looking ahead, you might notice that this half step is a ii-I interval in Phrygian mode: hence the name Phrygian half cadence.

Note that a common mistake in writing phrygian cadences is the possibility to write an augmented second in a voice if you are not careful. If, for some reason, you have to double the third of the chord in the iv6 chord, then make sure that it does not lead into the third of the chord of the V chord – otherwise, you will get a dissonant augmented second in one of the voices.

Also, don’t forget to raise the leading tone in the V chord!

Phrygian half cadences were used quite frequently to end slow movements that move into faster movements, especially in Baroque music. They fell out of use in the Romantic and Modern periods, so using them gives a little bit of a “vintage” sound.

Deceptive Cadences

A deceptive cadence is a cadence where the dominant chord (V) resolves to something other than tonic, almost always the submediant chord (vi or VI). You’ll usually see this type of cadence inside of sections of music or inside of a piece – it is almost never used to end a piece of music.

Here is an example of a deceptive cadence:

One thing to note is that there are “layers” of deceptive cadences. A V-vi deceptive cadence is much more common and less unsettling than a V-IV or V-iv deceptive cadence, for example.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.