Browse By Unit

Mickey Hansen

Mickey Hansen

When talking about rhythm, there are some terms that can help us describe specific features in music.

Syncopation and Polyrhythms

Syncopation is a rhythmic technique that involves shifting the accent of the music from its expected or normal accent pattern to a weak or off-beat rhythm. When we talk about syncopation, we are hearing the disruption of the established beat.This sometimes adds a playful feel to the music. Syncopation is often used in various forms of popular and classical music, including jazz, rock, and Latin music.

One of the most common forms of syncopation involves taking a normally accented note and placing it on a weaker or off-beat rhythm. For example, a typically accented note might occur on the first beat of a measure, but in syncopation, it might be placed on the off-beat between the first and second beats. For example, if the main beats are on 1, 2, 3 or 4, syncopation might be a 16th note ahead of each of those beats.

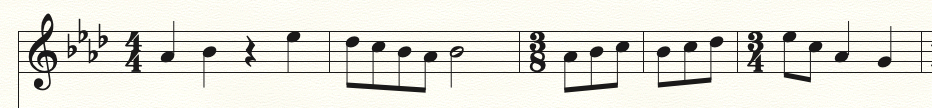

Polyrhythms are rhythms in which the voices subdivide the beat in a way that doesn’t line up. For example, a simple polyrhythm might be playing three beats against two beats or four beats against three beats. The example below is a common occurrence in music, and it requires extra dexterity if you were to play this example as a pianist, harpist, or percussionist!

Stravinsky is famous (infamous?) for using a lot of polyrhythms in his work. The polyrhythms produce “magical” and “free” textures, which is why they were used commonly in his etudes. Another good example of polyrhythms occurs in Debussy’s Arabesque No 1.

Here is an example of a 3-2 polyrhythm:

Hemiolas

A hemiola is a bit of an aural illusion. During a hemiola, the time signature stays as originally written, but the feeling is as if the meter has shifted. For example, in a 2/4 meter, if there are suddenly three notes every measure, the feeling is as if the meter has changed to 3/4 or 3/8 in a different tempo, but when reading the music, the notes are still aligned in a 2/4 bar.

The two different rhythmic structures that create a hemiola can either be heard one after the other or at the same time, with the latter forming an example of a polyrhythm known as a "two-against-three" pattern.

There are two other common ways a hemiola can present in music. First, if we are in compound duple meter (e.g. 6/8 time) and we include measures that articulate a simple triple meter (e.g. ¾ time) then we will hear a hemiola. This is because 6/8 time has two “big beats,” and ¾ time has three “big beats”, so in this method, we delay the strong beat in a hemiola until the second beat of a measure in 6/8 time.

Second, if we accent the third beat of triple meter, so we hear the beats as “Strong weak Strong” | “weak Strong weak” instead of “Strong weak weak” | “Strong weak weak”, we will have a different type of hemiola.

Just like syncopation disrupts the beat of the music, hemiolas disrupt the metrical organization of the music. The term “hemiola” is derived from the Greek word “hemi,” meaning “half,” and “ola,” meaning “a complete unit.” In other words, hemiolas are rhythmic patterns that are partially divided into two different rhythmic units. This creates a feeling of conflict between the two different rhythmic groupings, and this conflict is what gives hemiolas their unique character.

One of the most famous examples of a hemiola can be found in the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. In this piece, the hemiola is used to create a sense of rhythmic propulsion, and it is also used to emphasize the final cadence of the piece. The hemiola helps to bring the piece to a close and gives it a sense of conclusion and resolution.

Another example of a hemiola can be found in the third movement of Brahms’ Symphony No. 2. In this piece, the hemiola is used to create a feeling of conflict between the two different rhythms, and it is also used to create a sense of forward motion. The hemiola helps to drive the piece forward and gives it a sense of momentum.

Listen to these two pieces and see if you can find the hemiolas.

Accents

An agogic accent is a note that naturally receives more emphasis due to its extended duration, or accents that are placed in an unnatural flow of the established meter. It is a non-metric accent and occurs when a note is played longer for a longer value than the ones around it. The term "agogic" comes from the Greek word "ágogos", which means "leading" or "exciting". An agogic accent can also be used to change the perceived rhythm or meter of a piece of music, and can add a sense of forward momentum or direction.

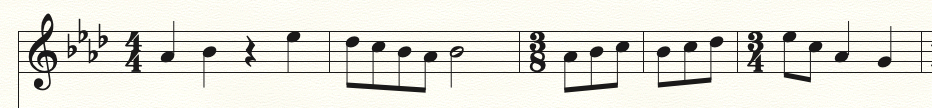

Here is an example from Mozart - Fantasia D-moll, K. 397

Image via The Leading Tone

Notice how these notes are played for a longer duration than the ones around it. Since these are placed on strong beats, they emphasize the given meter. However, if they were played on weak beats, they would alter our perception of the meter.

Other types of accent markings in music include accents, marcatos, staccatos, staccatissimos, and tenutos. Accents, which are denoted by a horizontal wedge above a note, signify that the note should be played more loudly and in a more pronounced manner than the notes around it. This marking is also sometimes denoted as a sforzando, notated as “sfz.” Marcatos are just like accent marks, although they usually occur when multiple notes in a row should be accented.

Staccatos and staccatissimos mean to play the note shorter than the written value. Staccatos don’t always mean to play the note short, just shorter than the written value so that there is separation between the notes. You usually interpret how short to play staccatos based on the musical context. Staccatissimos, on the other hand, do mean that you should play the note really short.

Finally, tenuto markings mean to play the notes at full length, but separated.

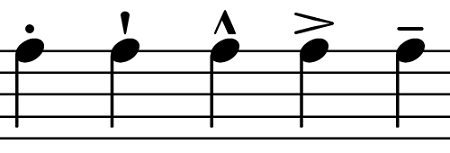

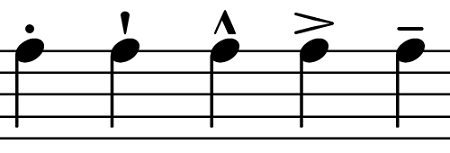

Here are the traditional markings for these types of accents, although you should note that the markings vary widely between composers and time periods, and even if composers use the same markings, they might mean different things based on context.

From left to right, they are: staccato, staccatissimo, marcato, accent, and tenuto.

Image via Study.com

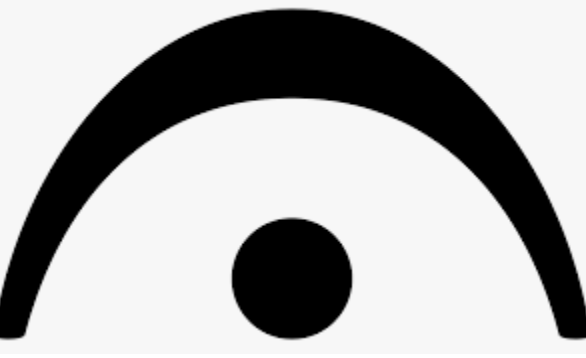

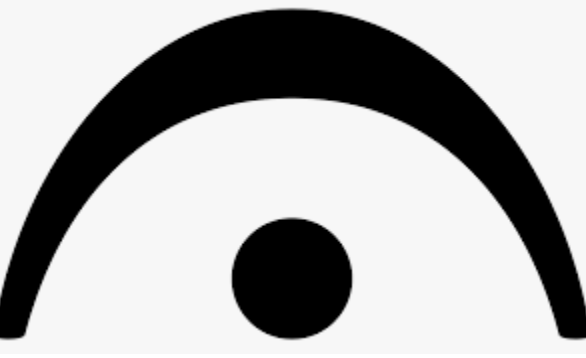

A fermata is a symbol placed over a note or rest that indicates that it is to be held longer than its normal duration. The length of the hold is at the discretion of the performer, but it is usually longer than the notated value. It is used to add emphasis or to bring attention to a particular section of a piece. A fermata is often used to allow the performer to take a breath, regroup, or make a dramatic pause. The symbol looks like an inverted semi-circle that is placed above or below the note or rest to be prolonged.

You’ll usually find fermatas at the end of pieces or in between sections of pieces. Here's what a fermata looks like:

Meter Types

An anacrusis is the same thing as a pickup. It refers to the notes that start a phrase before the first downbeat. It refers to a group of notes that occur before the first strong beat of a bar or phrase, creating an anticipatory effect and helping to establish the rhythm and pulse of the piece. Anacrusis can be used to create tension and energy, or to add a sense of momentum to the music. An anacrusis usually doesn’t affect the listener’s perception of the rhythm

Asymmetrical and Irregular Meters

When examining types of meter in music, we may come across meters such as 5/8 or 7/8. The subdivisions of these meters are not symmetrical, meaning we count them in groups of either two or three groups of 8th notes. In 5/8 meter, we can have either a two-three or three-two pulse. In 7/8, we could feel the pulse in two-three-two, two-two-three, or three-two-two. These are examples of asymmetrical or irregular meter.

There are many pieces written in asymmetrical meter in classical music, although they only really emerged in the 20th century. Here are a few examples:

- Igor Stravinsky's Rite of Spring

- Béla Bartók's Mikrokosmos

- Arnold Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra

- Paul Hindemith's Mathis der Maler

- Claude Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun

- Edgard Varèse's Ionisation

- Steve Reich's Music for 18 Musicians

- Philip Glass's Music with Changing Parts

Sometimes, music may use time signatures that shift often, such as a measure of 3/4 followed by a measure of 2/4. This is known as changing or mixed meter. However, this is not a common occurrence – usually, composers will just imply the mixed meter by using hemiolas or other rhythmic devices.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: What are the ways to subdivide a piece in 5/4 time? Does it makes a different if the tempo were allegro versus largo?

<< Hide Menu

Mickey Hansen

Mickey Hansen

When talking about rhythm, there are some terms that can help us describe specific features in music.

Syncopation and Polyrhythms

Syncopation is a rhythmic technique that involves shifting the accent of the music from its expected or normal accent pattern to a weak or off-beat rhythm. When we talk about syncopation, we are hearing the disruption of the established beat.This sometimes adds a playful feel to the music. Syncopation is often used in various forms of popular and classical music, including jazz, rock, and Latin music.

One of the most common forms of syncopation involves taking a normally accented note and placing it on a weaker or off-beat rhythm. For example, a typically accented note might occur on the first beat of a measure, but in syncopation, it might be placed on the off-beat between the first and second beats. For example, if the main beats are on 1, 2, 3 or 4, syncopation might be a 16th note ahead of each of those beats.

Polyrhythms are rhythms in which the voices subdivide the beat in a way that doesn’t line up. For example, a simple polyrhythm might be playing three beats against two beats or four beats against three beats. The example below is a common occurrence in music, and it requires extra dexterity if you were to play this example as a pianist, harpist, or percussionist!

Stravinsky is famous (infamous?) for using a lot of polyrhythms in his work. The polyrhythms produce “magical” and “free” textures, which is why they were used commonly in his etudes. Another good example of polyrhythms occurs in Debussy’s Arabesque No 1.

Here is an example of a 3-2 polyrhythm:

Hemiolas

A hemiola is a bit of an aural illusion. During a hemiola, the time signature stays as originally written, but the feeling is as if the meter has shifted. For example, in a 2/4 meter, if there are suddenly three notes every measure, the feeling is as if the meter has changed to 3/4 or 3/8 in a different tempo, but when reading the music, the notes are still aligned in a 2/4 bar.

The two different rhythmic structures that create a hemiola can either be heard one after the other or at the same time, with the latter forming an example of a polyrhythm known as a "two-against-three" pattern.

There are two other common ways a hemiola can present in music. First, if we are in compound duple meter (e.g. 6/8 time) and we include measures that articulate a simple triple meter (e.g. ¾ time) then we will hear a hemiola. This is because 6/8 time has two “big beats,” and ¾ time has three “big beats”, so in this method, we delay the strong beat in a hemiola until the second beat of a measure in 6/8 time.

Second, if we accent the third beat of triple meter, so we hear the beats as “Strong weak Strong” | “weak Strong weak” instead of “Strong weak weak” | “Strong weak weak”, we will have a different type of hemiola.

Just like syncopation disrupts the beat of the music, hemiolas disrupt the metrical organization of the music. The term “hemiola” is derived from the Greek word “hemi,” meaning “half,” and “ola,” meaning “a complete unit.” In other words, hemiolas are rhythmic patterns that are partially divided into two different rhythmic units. This creates a feeling of conflict between the two different rhythmic groupings, and this conflict is what gives hemiolas their unique character.

One of the most famous examples of a hemiola can be found in the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. In this piece, the hemiola is used to create a sense of rhythmic propulsion, and it is also used to emphasize the final cadence of the piece. The hemiola helps to bring the piece to a close and gives it a sense of conclusion and resolution.

Another example of a hemiola can be found in the third movement of Brahms’ Symphony No. 2. In this piece, the hemiola is used to create a feeling of conflict between the two different rhythms, and it is also used to create a sense of forward motion. The hemiola helps to drive the piece forward and gives it a sense of momentum.

Listen to these two pieces and see if you can find the hemiolas.

Accents

An agogic accent is a note that naturally receives more emphasis due to its extended duration, or accents that are placed in an unnatural flow of the established meter. It is a non-metric accent and occurs when a note is played longer for a longer value than the ones around it. The term "agogic" comes from the Greek word "ágogos", which means "leading" or "exciting". An agogic accent can also be used to change the perceived rhythm or meter of a piece of music, and can add a sense of forward momentum or direction.

Here is an example from Mozart - Fantasia D-moll, K. 397

Image via The Leading Tone

Notice how these notes are played for a longer duration than the ones around it. Since these are placed on strong beats, they emphasize the given meter. However, if they were played on weak beats, they would alter our perception of the meter.

Other types of accent markings in music include accents, marcatos, staccatos, staccatissimos, and tenutos. Accents, which are denoted by a horizontal wedge above a note, signify that the note should be played more loudly and in a more pronounced manner than the notes around it. This marking is also sometimes denoted as a sforzando, notated as “sfz.” Marcatos are just like accent marks, although they usually occur when multiple notes in a row should be accented.

Staccatos and staccatissimos mean to play the note shorter than the written value. Staccatos don’t always mean to play the note short, just shorter than the written value so that there is separation between the notes. You usually interpret how short to play staccatos based on the musical context. Staccatissimos, on the other hand, do mean that you should play the note really short.

Finally, tenuto markings mean to play the notes at full length, but separated.

Here are the traditional markings for these types of accents, although you should note that the markings vary widely between composers and time periods, and even if composers use the same markings, they might mean different things based on context.

From left to right, they are: staccato, staccatissimo, marcato, accent, and tenuto.

Image via Study.com

A fermata is a symbol placed over a note or rest that indicates that it is to be held longer than its normal duration. The length of the hold is at the discretion of the performer, but it is usually longer than the notated value. It is used to add emphasis or to bring attention to a particular section of a piece. A fermata is often used to allow the performer to take a breath, regroup, or make a dramatic pause. The symbol looks like an inverted semi-circle that is placed above or below the note or rest to be prolonged.

You’ll usually find fermatas at the end of pieces or in between sections of pieces. Here's what a fermata looks like:

Meter Types

An anacrusis is the same thing as a pickup. It refers to the notes that start a phrase before the first downbeat. It refers to a group of notes that occur before the first strong beat of a bar or phrase, creating an anticipatory effect and helping to establish the rhythm and pulse of the piece. Anacrusis can be used to create tension and energy, or to add a sense of momentum to the music. An anacrusis usually doesn’t affect the listener’s perception of the rhythm

Asymmetrical and Irregular Meters

When examining types of meter in music, we may come across meters such as 5/8 or 7/8. The subdivisions of these meters are not symmetrical, meaning we count them in groups of either two or three groups of 8th notes. In 5/8 meter, we can have either a two-three or three-two pulse. In 7/8, we could feel the pulse in two-three-two, two-two-three, or three-two-two. These are examples of asymmetrical or irregular meter.

There are many pieces written in asymmetrical meter in classical music, although they only really emerged in the 20th century. Here are a few examples:

- Igor Stravinsky's Rite of Spring

- Béla Bartók's Mikrokosmos

- Arnold Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra

- Paul Hindemith's Mathis der Maler

- Claude Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun

- Edgard Varèse's Ionisation

- Steve Reich's Music for 18 Musicians

- Philip Glass's Music with Changing Parts

Sometimes, music may use time signatures that shift often, such as a measure of 3/4 followed by a measure of 2/4. This is known as changing or mixed meter. However, this is not a common occurrence – usually, composers will just imply the mixed meter by using hemiolas or other rhythmic devices.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: What are the ways to subdivide a piece in 5/4 time? Does it makes a different if the tempo were allegro versus largo?

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.