Browse By Unit

Mickey Hansen

Mickey Hansen

Without expressive elements of music, the music we hear would be quite plain and boring. <gif>

Expressive elements include dynamics, articulation, and tempo.

Tempo explains the speed of the beat in music. t is typically measured in beats per minute (bpm) and indicated at the beginning of a piece of sheet music with a metronome marking. The tempo of a piece of music can affect its mood and can vary widely, from slow and solemn to fast and energetic.

At the start of the written Western music tradition, the Italian language 🇮🇹 was used in all the tempo markings, regardless of one's nationality. Throughout music history, other languages have also been used for both tempo markings and all expression markings, especially from the German 🇩🇪, French 🇫🇷, and English 🇬🇧 linguistic and musical traditions.

Today, we continue to use the Italian terminology to indicate tempi (the Italian plural for tempos) that are fast, slow and everything in between. Performers are held responsible for learning the meaning of the tempo markings, regardless of the language.

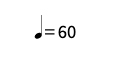

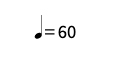

Sometimes, instead of a tempo marking, a composer will just write a metronome marking, which indicates how many BPM, or Beats Per Minute, a piece should be played. For example, a composition may label the start of a piece or a movement with the following:

This would mean that the quarter note receives a BPM of 60.

The most widely-used Italian tempo indicators, from slowest to fastest, are:

Grave—slow and solemn (20–40 BPM)

Lento—slowly (40–45 BPM)

Largo—broadly (45–50 BPM)

Larghetto—rather broadly (60-66 BPM)

Adagio—slow and stately (literally, “at ease”) (66–73 BPM)

Andante—at a walking pace (73–77 BPM)

Andantino—slightly faster walking pace (78–83 BPM)

Moderato—moderately (86–97 BPM)

Allegretto—moderately fast (98–109 BPM)

Allegro—fast, quickly and bright (109–132 BPM)

Vivace—lively and fast (132–140 BPM)

Presto—extremely fast (168–177 BPM)

Prestissimo—even faster than Presto (178 BPM and over)

You must know these terms for the AP Music Theory test! Note that while the beats per minute are given for each of the tempo markings, they are not hard and fast rules. Instead, think of tempo markings as feelings or moods that you want to encapture. For example, Andante or Andantino is in fact slower than Vivace, but a piece in Andante is also more casual, laid back, and measured because pieces in Andante want to capture the feeling of "walking".

It is helpful to know what the exact translations of the Italian tempo markings are in English. For example, "grave" means "serious" and "ellegro" means "cheerful." These are the feelings that you want to capture when you are interpreting a piece. Often, if you're unsure about the exact tempo marking on a piece, you might be able to guess based on both the mood and the speed.

The beats per minute also might not be a good measure of tempo because the feeling of tempo depends on how many beat divisions there are. Listen to Rachmaninoff's Moment Musicaux No. 4. If I told you that it is in common time, what tempo marking do you think is given? If you said Presto, you would be correct! But how many beats per minute do you think there are? Believe it or not, one quarter note (one beat) is 104 bpm.

Still, it is important to have a good idea of what different tempo markings sound like.

Click below to hear what largo at 44 BPM sounds like.

Listen to the speed of 44 metronome BPM!

Click below to hear what prestissimo at 184 BPM sounds like.

Listen to the speed of 184 metronome BPM!

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: Between largo and larghetto, which is faster? Between allegretto and allegro, which is slower?

Changes in Tempo

To alter the tempo, there are also a few tempo marking in Italian we need to learn:

Ritardando—slowing down gradually

Ritenuto—slowing down abruptly

Acclerando—slowly speeding up

Rubato—freedom with the tempo

Ritardando is a musical term that means "slowing down." It is often used in sheet music to indicate that the tempo of the music should slow down gradually. Ritardando is typically used to add expression and drama to a piece of music. It is also often used at the end of a phrase or section to create a sense of resolution or to build suspense.

In sheet music, ritardando can be indicated by the abbreviation "rit." followed by a dotted line, which indicates the extent of the tempo change. The performer should use their discretion and musical judgment to determine the exact speed at which to play the ritardando. Usually, the composer will not write ritardando to x amount of tempo, or ritardando until x measure. You should use the phrasing and the part of the piece in which the ritardando is located to determine these details.

Sometimes, you'll see a slowing down called "ralletando." You are not required to know this for the AP exam, but for your own musical knowledge, you might wonder what the difference is between the two tempo markings. Usually, rallentando is more dramatic: it is an expressive and intentional slowing down. Usually, rallentando is accompanied by a diminuendo (where the volume gets quieter). Ritardando might be expressive, but it might also be very subtle.

A specific type of ritardando is called a ritenuto, which means slowing down abruptly. Funnily enough, ritenuto is also usually written as "rit." in sheet music. Usually, you can tell whether something is a ritenuto or a ritardando based on the context, and sometimes, the dotted line following the "rit." However, some composers just don't use the dotted line at all, so you should rely mostly on context clues. If you do find a dotted line, though, you can use it to figure out the length of the ritenuto.

Accelerando is a term used to indicate that the tempo or speed of the music should gradually increase. It is abbreviated as "accel." and is often written in Italian as "accelerando" or "a tempo". The term is typically found in written musical scores and is used to instruct the performers to gradually speed up the tempo of the piece as they play. This can be achieved by increasing the speed at which the notes are played or by simply playing the notes more loudly and with more energy, which can give the impression of an increase in tempo.

Sometimes, an accelerando is written as "stringendo," which also tells the musician to speed up. Just like rallentando, stringendo is a more intense version of accelerando. It literally translates to "tightening."

It's harder to find examples of accelerando in music, but one famous one is Grieg's "In the Hall of the Mountain King." Although this has several measures becoming increasingly faster, it is not always the case that accelerando has to occur over lots of measures. It might just be one or two measures that are getting faster.

After any of the above tempo markings, you might see the phrase "poco a poco," meaning little by little. This is common in some types of music, but not others.

Finally, rubato is a musical term that refers to the flexibility of tempo in a piece of music. It literally means "stolen time," and is often described as a "give and take" of tempo, where the musician speeds up or slows down slightly for expressive purposes.

Rubato is typically used in solo instrumental music or in singing, and is usually notated in the sheet music with specific instructions for the performer. It is important for the performer to use rubato tastefully and not disrupt the overall flow of the music.

Rubato can be used to add interest and expression to a performance, but it should be used with caution and in moderation. In some styles of music, such as classical music, rubato is more commonly used, while in other styles, such as jazz or rock, a more steady tempo is generally preferred.

In classical music, rubato has a very interesting history. It was not used at all in the Baroque period, and it was used very sparingly in the classical period -- it is unlikely that you will find a rubato marking in Bach or Mozart. Beethoven was largely responsible for pushing us into the Romantic period, so rubatos were used in some of his later works. As we move into the Romantic and Modern periods of music, though, we again might not see rubatos, because we just assume that they are there! Chopin's Nocturnes, for example, will very rarely indicate "rubato" on the score, but there is a great deal of push and pull in the music.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker! Listen to Debussy's Arabesque No. 1. What do you think is the overall tempo marking? Do you notice ritardandos, accelerandos, and rubatos? What musical period do you think it was written in?

<< Hide Menu

Mickey Hansen

Mickey Hansen

Without expressive elements of music, the music we hear would be quite plain and boring. <gif>

Expressive elements include dynamics, articulation, and tempo.

Tempo explains the speed of the beat in music. t is typically measured in beats per minute (bpm) and indicated at the beginning of a piece of sheet music with a metronome marking. The tempo of a piece of music can affect its mood and can vary widely, from slow and solemn to fast and energetic.

At the start of the written Western music tradition, the Italian language 🇮🇹 was used in all the tempo markings, regardless of one's nationality. Throughout music history, other languages have also been used for both tempo markings and all expression markings, especially from the German 🇩🇪, French 🇫🇷, and English 🇬🇧 linguistic and musical traditions.

Today, we continue to use the Italian terminology to indicate tempi (the Italian plural for tempos) that are fast, slow and everything in between. Performers are held responsible for learning the meaning of the tempo markings, regardless of the language.

Sometimes, instead of a tempo marking, a composer will just write a metronome marking, which indicates how many BPM, or Beats Per Minute, a piece should be played. For example, a composition may label the start of a piece or a movement with the following:

This would mean that the quarter note receives a BPM of 60.

The most widely-used Italian tempo indicators, from slowest to fastest, are:

Grave—slow and solemn (20–40 BPM)

Lento—slowly (40–45 BPM)

Largo—broadly (45–50 BPM)

Larghetto—rather broadly (60-66 BPM)

Adagio—slow and stately (literally, “at ease”) (66–73 BPM)

Andante—at a walking pace (73–77 BPM)

Andantino—slightly faster walking pace (78–83 BPM)

Moderato—moderately (86–97 BPM)

Allegretto—moderately fast (98–109 BPM)

Allegro—fast, quickly and bright (109–132 BPM)

Vivace—lively and fast (132–140 BPM)

Presto—extremely fast (168–177 BPM)

Prestissimo—even faster than Presto (178 BPM and over)

You must know these terms for the AP Music Theory test! Note that while the beats per minute are given for each of the tempo markings, they are not hard and fast rules. Instead, think of tempo markings as feelings or moods that you want to encapture. For example, Andante or Andantino is in fact slower than Vivace, but a piece in Andante is also more casual, laid back, and measured because pieces in Andante want to capture the feeling of "walking".

It is helpful to know what the exact translations of the Italian tempo markings are in English. For example, "grave" means "serious" and "ellegro" means "cheerful." These are the feelings that you want to capture when you are interpreting a piece. Often, if you're unsure about the exact tempo marking on a piece, you might be able to guess based on both the mood and the speed.

The beats per minute also might not be a good measure of tempo because the feeling of tempo depends on how many beat divisions there are. Listen to Rachmaninoff's Moment Musicaux No. 4. If I told you that it is in common time, what tempo marking do you think is given? If you said Presto, you would be correct! But how many beats per minute do you think there are? Believe it or not, one quarter note (one beat) is 104 bpm.

Still, it is important to have a good idea of what different tempo markings sound like.

Click below to hear what largo at 44 BPM sounds like.

Listen to the speed of 44 metronome BPM!

Click below to hear what prestissimo at 184 BPM sounds like.

Listen to the speed of 184 metronome BPM!

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: Between largo and larghetto, which is faster? Between allegretto and allegro, which is slower?

Changes in Tempo

To alter the tempo, there are also a few tempo marking in Italian we need to learn:

Ritardando—slowing down gradually

Ritenuto—slowing down abruptly

Acclerando—slowly speeding up

Rubato—freedom with the tempo

Ritardando is a musical term that means "slowing down." It is often used in sheet music to indicate that the tempo of the music should slow down gradually. Ritardando is typically used to add expression and drama to a piece of music. It is also often used at the end of a phrase or section to create a sense of resolution or to build suspense.

In sheet music, ritardando can be indicated by the abbreviation "rit." followed by a dotted line, which indicates the extent of the tempo change. The performer should use their discretion and musical judgment to determine the exact speed at which to play the ritardando. Usually, the composer will not write ritardando to x amount of tempo, or ritardando until x measure. You should use the phrasing and the part of the piece in which the ritardando is located to determine these details.

Sometimes, you'll see a slowing down called "ralletando." You are not required to know this for the AP exam, but for your own musical knowledge, you might wonder what the difference is between the two tempo markings. Usually, rallentando is more dramatic: it is an expressive and intentional slowing down. Usually, rallentando is accompanied by a diminuendo (where the volume gets quieter). Ritardando might be expressive, but it might also be very subtle.

A specific type of ritardando is called a ritenuto, which means slowing down abruptly. Funnily enough, ritenuto is also usually written as "rit." in sheet music. Usually, you can tell whether something is a ritenuto or a ritardando based on the context, and sometimes, the dotted line following the "rit." However, some composers just don't use the dotted line at all, so you should rely mostly on context clues. If you do find a dotted line, though, you can use it to figure out the length of the ritenuto.

Accelerando is a term used to indicate that the tempo or speed of the music should gradually increase. It is abbreviated as "accel." and is often written in Italian as "accelerando" or "a tempo". The term is typically found in written musical scores and is used to instruct the performers to gradually speed up the tempo of the piece as they play. This can be achieved by increasing the speed at which the notes are played or by simply playing the notes more loudly and with more energy, which can give the impression of an increase in tempo.

Sometimes, an accelerando is written as "stringendo," which also tells the musician to speed up. Just like rallentando, stringendo is a more intense version of accelerando. It literally translates to "tightening."

It's harder to find examples of accelerando in music, but one famous one is Grieg's "In the Hall of the Mountain King." Although this has several measures becoming increasingly faster, it is not always the case that accelerando has to occur over lots of measures. It might just be one or two measures that are getting faster.

After any of the above tempo markings, you might see the phrase "poco a poco," meaning little by little. This is common in some types of music, but not others.

Finally, rubato is a musical term that refers to the flexibility of tempo in a piece of music. It literally means "stolen time," and is often described as a "give and take" of tempo, where the musician speeds up or slows down slightly for expressive purposes.

Rubato is typically used in solo instrumental music or in singing, and is usually notated in the sheet music with specific instructions for the performer. It is important for the performer to use rubato tastefully and not disrupt the overall flow of the music.

Rubato can be used to add interest and expression to a performance, but it should be used with caution and in moderation. In some styles of music, such as classical music, rubato is more commonly used, while in other styles, such as jazz or rock, a more steady tempo is generally preferred.

In classical music, rubato has a very interesting history. It was not used at all in the Baroque period, and it was used very sparingly in the classical period -- it is unlikely that you will find a rubato marking in Bach or Mozart. Beethoven was largely responsible for pushing us into the Romantic period, so rubatos were used in some of his later works. As we move into the Romantic and Modern periods of music, though, we again might not see rubatos, because we just assume that they are there! Chopin's Nocturnes, for example, will very rarely indicate "rubato" on the score, but there is a great deal of push and pull in the music.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker! Listen to Debussy's Arabesque No. 1. What do you think is the overall tempo marking? Do you notice ritardandos, accelerandos, and rubatos? What musical period do you think it was written in?

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.