Browse By Unit

1.5 Major Keys and Key Signatures

7 min read•june 18, 2024

Mickey Hansen

Mickey Hansen

Keys and Key Signatures

When the majority of a musical passage congregates around the pitches of a major or minor scale, we consider it to be within a certain key. For example, if the notes of an F major scale are used and F is considered a central pitch, the piece of music is referred to as "in the key of F major".

In the last section, we learned how to use key signatures to determine which key a piece is written in. Just to recap, a key signature is a group of symbols placed at the beginning of a piece of music that indicates the key of the piece. Key signatures are used to specify which notes are to be played as sharp or flat throughout the piece, regardless of the key in which the piece is written.

The key signature is placed on the same line as the treble clef and the time signature, and it appears immediately after the clef and time signature. It consists of one or more sharp or flat symbols, placed in a specific order, that indicate which notes are to be played as sharp or flat.

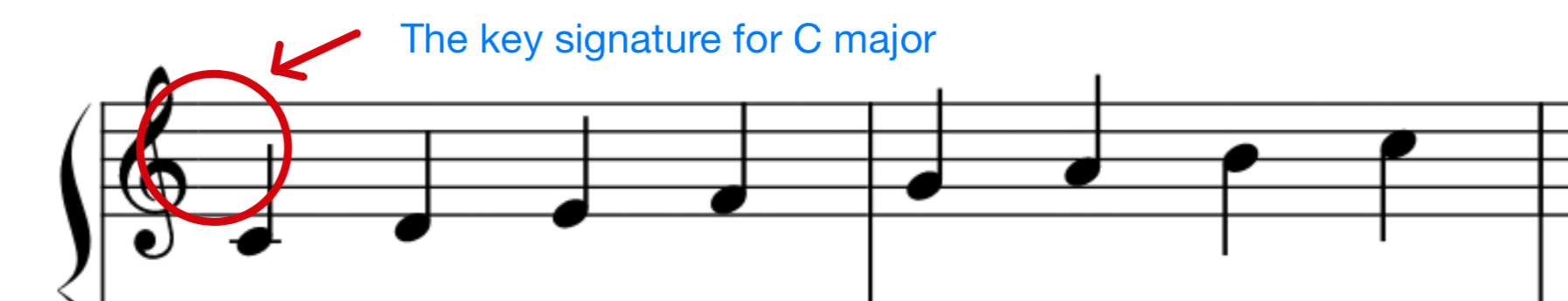

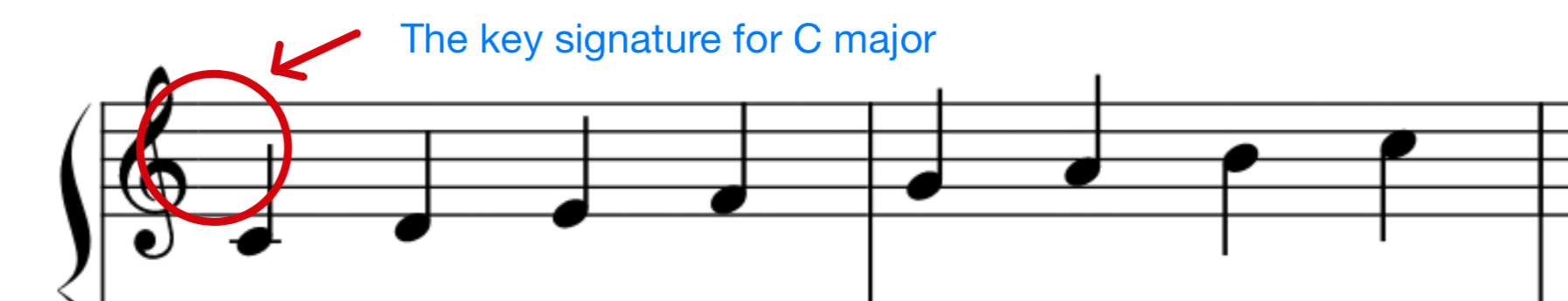

Remember the C Major scale? There weren't any flats or sharps.

The key signature is still there! It just shows that there are no flats or sharps to be used, therefore the key is C major.

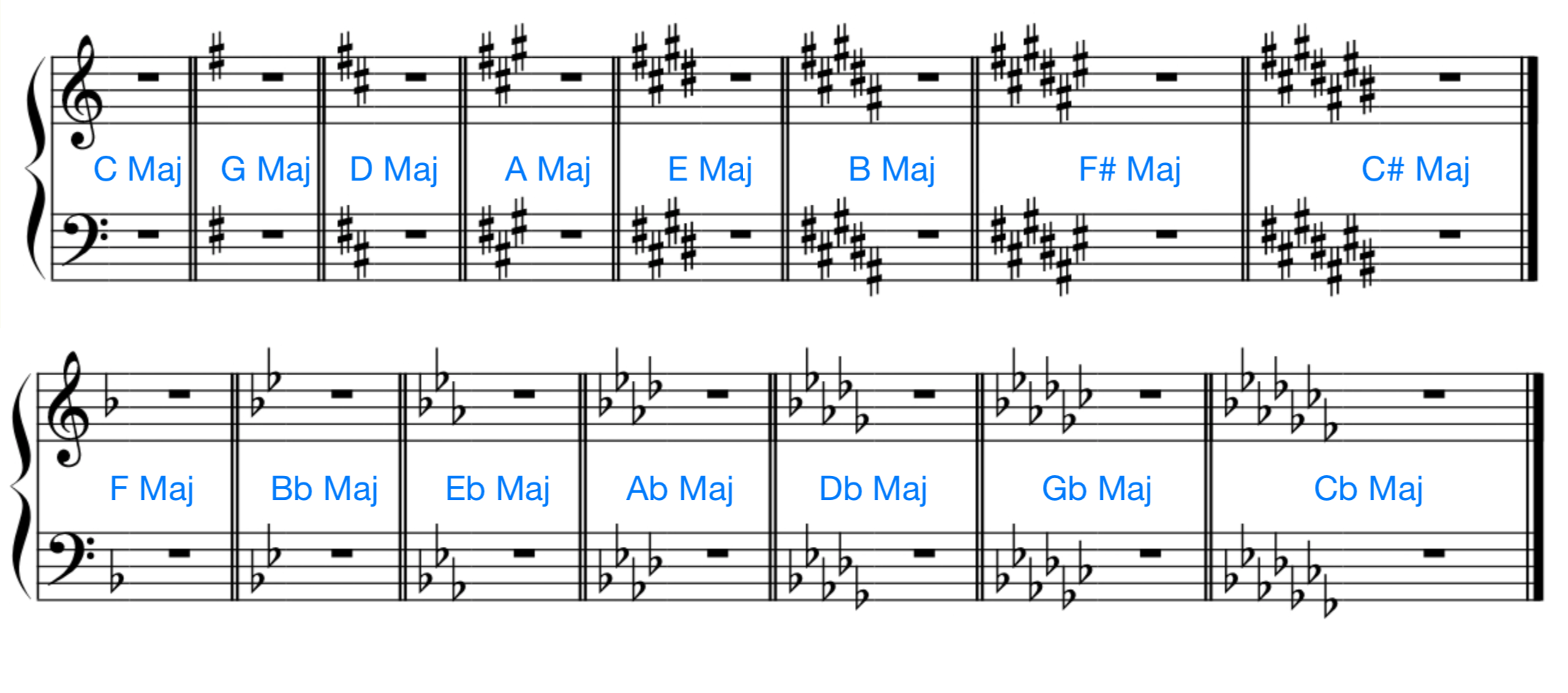

How many major keys are there in total? 12, one for each note of the chromatic scale. When calculating the 12, enharmonic equivalents are considered as 1 key, even though they have very different key signatures.

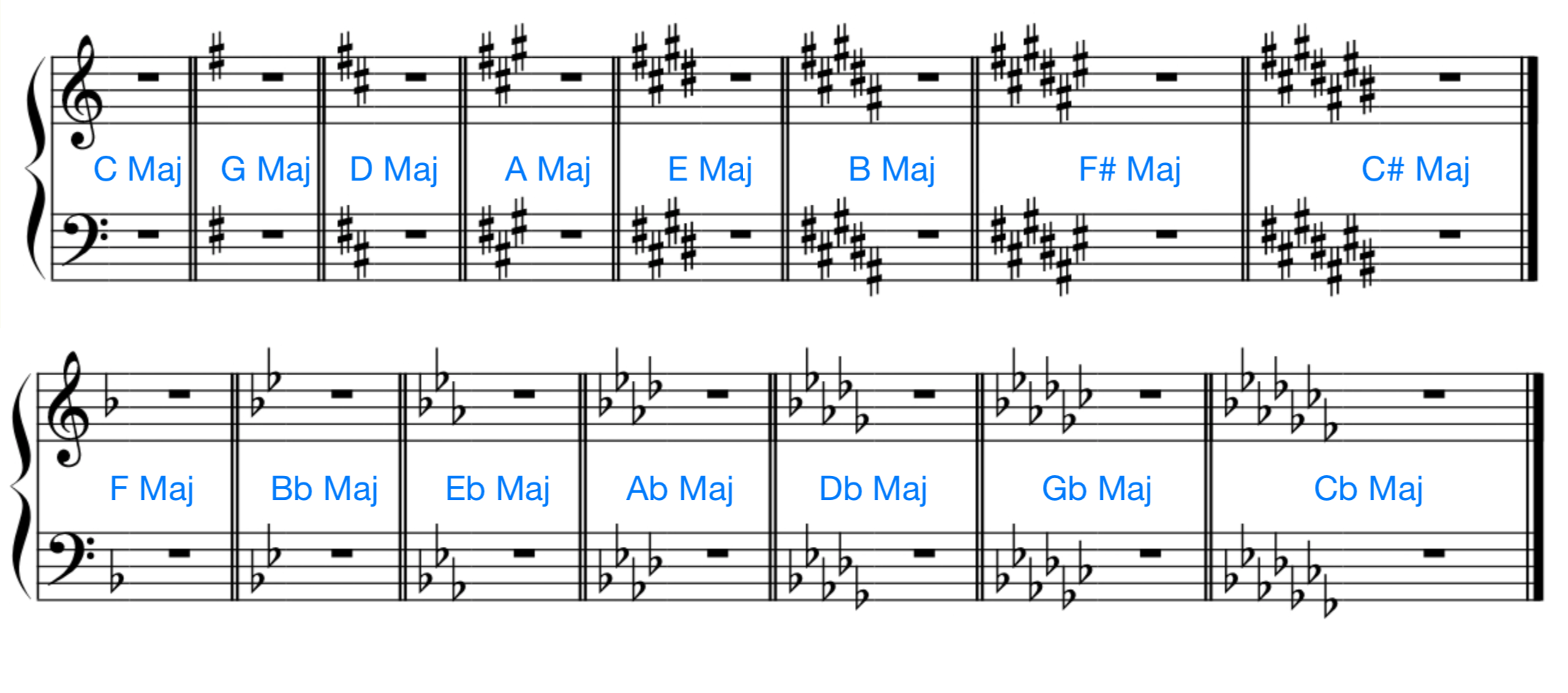

Below are all of the different key signatures. Note that Maj is short for major—you may frequently see that abbreviation.

The key signature is used to specify the tonality of a piece of music. In tonal music, the tonality is established by the key of the piece, which is determined by the tonic (the first degree of the scale). The tonic (first scale degree) is the most important note in the key, and the other notes of the scale are related to it by specific intervals.

For example, a key signature with one sharp indicates that the piece is in the key of G major or E minor. A key signature with two sharps indicates that the piece is in the key of D major or B minor. A key signature with one flat indicates that the piece is in the key of F major or D minor. A key signature with two flats indicates that the piece is in the key of Bb major or G minor.

Which key am I in?

Outside of pure memorization, there are a few tricks to remembering which keys we are in. When looking at the sharps, just look at the last sharp in the key signature, and go up a half step. For example, if the last sharp is D#, then you are in E Major.

Are you already asking for the trick for the flats?

There is one key signature with flats that you will need to simply memorize. Look at the table above with the flats. The first key signature just has one flat in the key, and that indicates F Major. Memorized? Great!

For all other flats, here is the trick: just take the second to last flat. For example, if your key signature has Bb, Eb, Ab, and Db, you are in Ab Major.

The Circle of Fifths

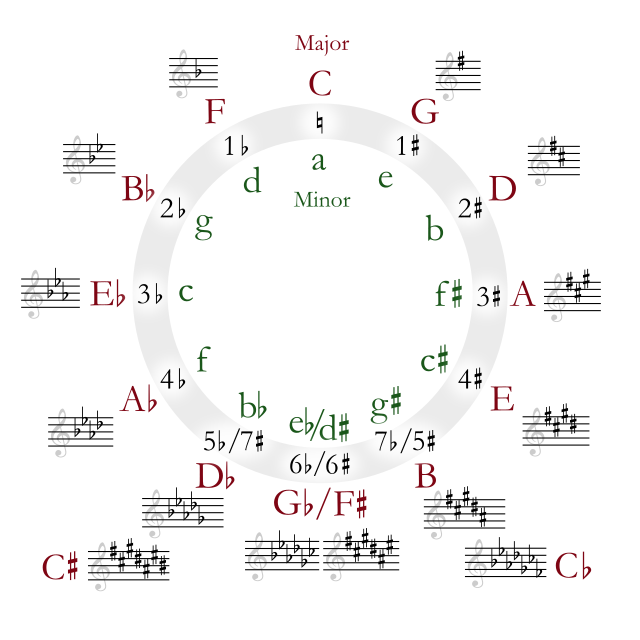

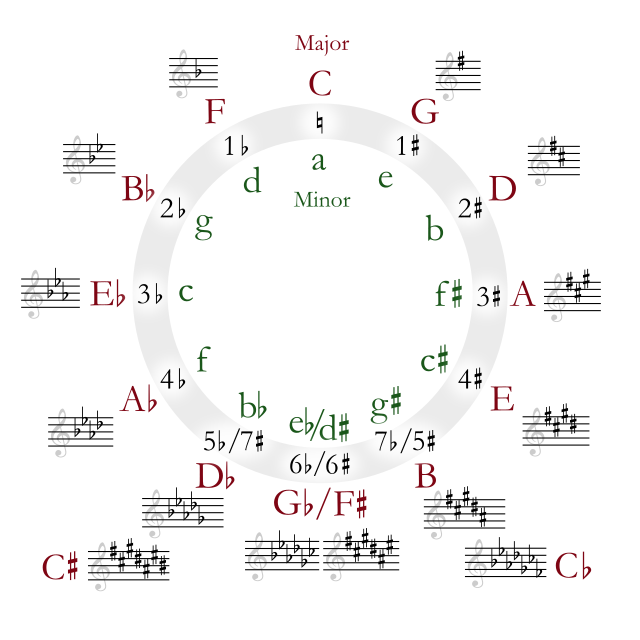

In the previous unit, we also learned that the circle of fifths is used to understand the relationships between different keys. It can also be used to help with the construction of chords and chord progressions and understand the relationships between major and minor keys.

The circle of fifths can also be used to understand the relationships between different keys. For example, if you start on C major and move clockwise around the circle by one fifth, you will arrive at G major. If you move counterclockwise by one fifth, you will arrive at F major. The keys that are closer together on the circle are more closely related, and the keys that are farther apart are less closely related.

What does it really mean when keys are closely related? In music theory, keys that are closely related are those that have many notes in common and a similar tonality. These keys are said to be closely related because they share many of the same chords and have a similar overall sound.

The circle of fifths shows which keys are a fifth apart and are therefore closely related. For example, the keys of C major and G major are closely related because they are a fifth apart on the circle of fifths. However, E major and E-flat major are not closely related at all, even though they're close together on the chromatic scale!

Another way to determine which keys are closely related is to compare the key signatures. Keys with similar key signatures are generally more closely related than those with different key signatures. For example, the keys of C major and G major are closely related because they have the same key signature (one sharp). In contrast, the keys of C major and F major are not as closely related because they have different key signatures (no sharps or flats for C major and one flat for F major).

In general, the keys that are closest together on the circle of fifths are the most closely related. These keys share many of the same chords and have a similar overall sound, which makes it easier to modulate (shift) between them. You'll learn more about modulation in Unit 5!

History Behind the Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths has been around for centuries and has been used by musicians and composers in various forms. It is believed to have originated in the Renaissance era, although the exact history of the circle of fifths is not well documented.

The term "circle of fifths" was first coined by German musician and theorist Johann David Heinichen in the early 18th century. However, the concept of the circle of fifths has roots that stretch back much further in musical history. It is thought to have originated in ancient Greek music theory, and it has been used by musicians in various cultures and traditions throughout the centuries.

I bring this up because it is important to recognize that the circle of fifths is a Western idea that popularized mostly through Western music. There are many well-developed styles of music that don't use the circle of fifths at all! Please note that while in AP Music Theory, we learn mostly Western music theory, music theory as a field covers a much broader and more diverse range of topics and music styles.

- Make sure you keep the flat in the name of the key signature, too For example, look at the measure labeled Gb major. You will see that the second-to-last flat is, indeed, over a Gb.

🦜Polly wants a progress tracker: What is the order of sharps? What is the order of flats? Can you create a mnemonic device to remember the order of each?

Notating and Singing Melodies in Major Keys

On the AP Music Theory exam, you might be asked to notate certain melodies in major scales. For this, it is important to memorize the relationships between notes on the major scale -- in other words, you have to know the major and perfect intervals. There are some songs our popular tunes that you can use to remember these intervals. Look at them here, or make your own list!

The pitch of the first note of the melody will be provided, along with the key signature. It is up to you to figure out which scale degree the first note is. Usually, it is the tonic. For example, if you are in E Major, and you are given the first pitch E, you know you're starting on the tonic. Another common choice for the first note of the melody is the dominant, or the fifth scale degree.

There are a few strategies to cracking this question. The first is to try to figure out which note is the tonic as quickly as possible. After that, it is easy to use your recognition of the major scale (do-re-mi, etc.) to fill in the rest of the notes. That way, you're not using your memorization of intervals to answer the full question.

The next tip is to know that usually, for major keys, there won't be more than 1 or 2 accidentals in the melody. Usually, there won't be any. If you are getting a lot of accidentals, then you probably got a wrong note early on, and you're comparing all of the other pitches to that note.

The last tip is to practice, practice, PRACTICE! You will get used to answering these questions over time. When I did the question, I would first figure out the pitches, and then plug in the rhythm later. Others might find it easier to do the opposite. Sightsinging practice also helps with these types of questions, and it will help you solve the sight-singing question on the exam as well, so it's a win-win!

There are some very good practice resources for learning sight singing and melody notation. The first and most obvious one is the AP Music Theory past exam questions. But this might seem overwhelming at first. Try working on smaller skills and then building up to more complex combinations of these skills. My favorite app for ear training was called Earpeggio, but there are several other options as well!

<< Hide Menu

1.5 Major Keys and Key Signatures

7 min read•june 18, 2024

Mickey Hansen

Mickey Hansen

Keys and Key Signatures

When the majority of a musical passage congregates around the pitches of a major or minor scale, we consider it to be within a certain key. For example, if the notes of an F major scale are used and F is considered a central pitch, the piece of music is referred to as "in the key of F major".

In the last section, we learned how to use key signatures to determine which key a piece is written in. Just to recap, a key signature is a group of symbols placed at the beginning of a piece of music that indicates the key of the piece. Key signatures are used to specify which notes are to be played as sharp or flat throughout the piece, regardless of the key in which the piece is written.

The key signature is placed on the same line as the treble clef and the time signature, and it appears immediately after the clef and time signature. It consists of one or more sharp or flat symbols, placed in a specific order, that indicate which notes are to be played as sharp or flat.

Remember the C Major scale? There weren't any flats or sharps.

The key signature is still there! It just shows that there are no flats or sharps to be used, therefore the key is C major.

How many major keys are there in total? 12, one for each note of the chromatic scale. When calculating the 12, enharmonic equivalents are considered as 1 key, even though they have very different key signatures.

Below are all of the different key signatures. Note that Maj is short for major—you may frequently see that abbreviation.

The key signature is used to specify the tonality of a piece of music. In tonal music, the tonality is established by the key of the piece, which is determined by the tonic (the first degree of the scale). The tonic (first scale degree) is the most important note in the key, and the other notes of the scale are related to it by specific intervals.

For example, a key signature with one sharp indicates that the piece is in the key of G major or E minor. A key signature with two sharps indicates that the piece is in the key of D major or B minor. A key signature with one flat indicates that the piece is in the key of F major or D minor. A key signature with two flats indicates that the piece is in the key of Bb major or G minor.

Which key am I in?

Outside of pure memorization, there are a few tricks to remembering which keys we are in. When looking at the sharps, just look at the last sharp in the key signature, and go up a half step. For example, if the last sharp is D#, then you are in E Major.

Are you already asking for the trick for the flats?

There is one key signature with flats that you will need to simply memorize. Look at the table above with the flats. The first key signature just has one flat in the key, and that indicates F Major. Memorized? Great!

For all other flats, here is the trick: just take the second to last flat. For example, if your key signature has Bb, Eb, Ab, and Db, you are in Ab Major.

The Circle of Fifths

In the previous unit, we also learned that the circle of fifths is used to understand the relationships between different keys. It can also be used to help with the construction of chords and chord progressions and understand the relationships between major and minor keys.

The circle of fifths can also be used to understand the relationships between different keys. For example, if you start on C major and move clockwise around the circle by one fifth, you will arrive at G major. If you move counterclockwise by one fifth, you will arrive at F major. The keys that are closer together on the circle are more closely related, and the keys that are farther apart are less closely related.

What does it really mean when keys are closely related? In music theory, keys that are closely related are those that have many notes in common and a similar tonality. These keys are said to be closely related because they share many of the same chords and have a similar overall sound.

The circle of fifths shows which keys are a fifth apart and are therefore closely related. For example, the keys of C major and G major are closely related because they are a fifth apart on the circle of fifths. However, E major and E-flat major are not closely related at all, even though they're close together on the chromatic scale!

Another way to determine which keys are closely related is to compare the key signatures. Keys with similar key signatures are generally more closely related than those with different key signatures. For example, the keys of C major and G major are closely related because they have the same key signature (one sharp). In contrast, the keys of C major and F major are not as closely related because they have different key signatures (no sharps or flats for C major and one flat for F major).

In general, the keys that are closest together on the circle of fifths are the most closely related. These keys share many of the same chords and have a similar overall sound, which makes it easier to modulate (shift) between them. You'll learn more about modulation in Unit 5!

History Behind the Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths has been around for centuries and has been used by musicians and composers in various forms. It is believed to have originated in the Renaissance era, although the exact history of the circle of fifths is not well documented.

The term "circle of fifths" was first coined by German musician and theorist Johann David Heinichen in the early 18th century. However, the concept of the circle of fifths has roots that stretch back much further in musical history. It is thought to have originated in ancient Greek music theory, and it has been used by musicians in various cultures and traditions throughout the centuries.

I bring this up because it is important to recognize that the circle of fifths is a Western idea that popularized mostly through Western music. There are many well-developed styles of music that don't use the circle of fifths at all! Please note that while in AP Music Theory, we learn mostly Western music theory, music theory as a field covers a much broader and more diverse range of topics and music styles.

- Make sure you keep the flat in the name of the key signature, too For example, look at the measure labeled Gb major. You will see that the second-to-last flat is, indeed, over a Gb.

🦜Polly wants a progress tracker: What is the order of sharps? What is the order of flats? Can you create a mnemonic device to remember the order of each?

Notating and Singing Melodies in Major Keys

On the AP Music Theory exam, you might be asked to notate certain melodies in major scales. For this, it is important to memorize the relationships between notes on the major scale -- in other words, you have to know the major and perfect intervals. There are some songs our popular tunes that you can use to remember these intervals. Look at them here, or make your own list!

The pitch of the first note of the melody will be provided, along with the key signature. It is up to you to figure out which scale degree the first note is. Usually, it is the tonic. For example, if you are in E Major, and you are given the first pitch E, you know you're starting on the tonic. Another common choice for the first note of the melody is the dominant, or the fifth scale degree.

There are a few strategies to cracking this question. The first is to try to figure out which note is the tonic as quickly as possible. After that, it is easy to use your recognition of the major scale (do-re-mi, etc.) to fill in the rest of the notes. That way, you're not using your memorization of intervals to answer the full question.

The next tip is to know that usually, for major keys, there won't be more than 1 or 2 accidentals in the melody. Usually, there won't be any. If you are getting a lot of accidentals, then you probably got a wrong note early on, and you're comparing all of the other pitches to that note.

The last tip is to practice, practice, PRACTICE! You will get used to answering these questions over time. When I did the question, I would first figure out the pitches, and then plug in the rhythm later. Others might find it easier to do the opposite. Sightsinging practice also helps with these types of questions, and it will help you solve the sight-singing question on the exam as well, so it's a win-win!

There are some very good practice resources for learning sight singing and melody notation. The first and most obvious one is the AP Music Theory past exam questions. But this might seem overwhelming at first. Try working on smaller skills and then building up to more complex combinations of these skills. My favorite app for ear training was called Earpeggio, but there are several other options as well!

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.